by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Facilitation

On a recent work trip to Ethiopia, I led and facilitated a group of 15 researchers collecting stories about adolescent girls for Girl Effect with SART, an Ethiopian Research company. We followed a BBC crew showing a documentary about stories of Ethiopian girls.

I used participatory leadership practices to build the team’s spirit and commitment to their work. For the team to take ownership of the process, they needed to understand the importance of women’s experiences. What better way for this to occur than on our own team? But in the meetings, the women were quiet.

A researcher collects a young storyteller’s story

1 / 4

StartStop

During the first two days of working together, I was frustrated. Everything I learned about facilitation was not working. One-on-one informal conversations flowed, but once the team was in a meeting, my opening question would be met with silence. “What are you learning about this community?” “What would you like to share about your experience today?” “Did anything stand out?” On the third day, the coordinator approached me and said: “Dr. Rita, the questions you ask, they’re too ….they’re too hard to answer. That’s why we’re quiet. We’re Ethiopian. We don’t like to break the ice. We prefer silence.”

I asked him to guide me in ways to overcome these challenges, and I learned to begin with more concrete questions (“Who facilitated groups today?” “Were young girls more responsive in smaller groups?” “Were girls looking for validation from facilitators?”). I also asked team members to respond to a question by going around in a circle, which made it easier for people to speak up, as their turn was designated and expected.

This worked well in debriefing the research process, but didn’t address team members’ emotional needs. Though the project was short, the two weeks of data collection were very intense ones for the researchers; the more they collected stories, the more stories of physical violence against children, rape, hunger, and tremendous poverty emerged. I could see the team becoming sad, worn out, and overwhelmed. I could sense the team spirit wavering.

I wanted to offer my support, yet, as a western researcher, it was unlikely that they would come to me. A strong sense of reserve and dignity kept team members from sharing their challenges. Still, I continued to hold space for the hard conversations in our meetings. At each meeting, I asked if there was discomfort, and I renewed my availability for anyone who needed me. “Are there any stories that were hard to hear?” “How do you feel collecting these stories?” All questions were met with silence, yet I was no longer worried. I could sense that spirits were not as heavy. Just by having the option to talk, members were lightening up.

Later, I asked the coordinator if team members ever talked about their experiences AFTER our meetings: “Yes, last night we did, and for quite a while.” “Good,” I said, “I don’t have to hear the conversation. I just want it to take place. As long as you go to each other about how this work makes you feel so you don’t burn out.”

I was happy hosting the silence that generated later conversations. I didn’t need to hear the whole conversation. Sometimes all a facilitator can do is host the silence that plants the seed for conversations to grow in better-suited contexts. English was not my researchers’ first language, and I was not a person from their culture. If the conversation didn’t take place in my presence it didn’t matter.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Facilitation

In 2012, I hosted a retreat for Kito International an organization in Nairobi, Kenya that trains street youth to establish their own businesses and move towards self-sufficiency. The founder Wiclif Otieno is an ex-street youth himself. In a country with a 75% unemployment rate for people ages 18-35, it is a painful truth that 300,000 youth live on the street.

Our purpose for the day was to envision the best possible future for the Kawangware community of Kito’s site and to identify ways to move in that direction.

The founder also wanted the organization to transition to peer-training by inviting two youth who completed the program to train other youth. We had a morning World Café with the guiding question: “What can we envision for Kawangware?”, a teach-in on the Chaordic Stepping Stones, an afternoonOpen Space with a guiding question: “What can we do together that we can’t do alone?”, and a Circle Council intended to facilitate making a decision about peer-training.

In a Circle Council, Circle Practice is used to make decisions by: 1) One member proposing a decision needing to be made; 2) Each member speaking their opinion and feelings about the decision; 3) Members speaking up on what is clear to them; 4) Creating a set of options; 5) Voting on the options; and 6) Building consensus by working with and modifying the most-supported option.

Circle Process in the Kito International home office and workshop site in Nairobi, Ken

1 / 3

StartStop

I chose to facilitate this decision-making structure because I was told there was disagreement among Kito’s stakeholders. I hoped that new, composite solutions would emerge via the overt expression of different opinions in the group.

After the founder presented the decision to participants, however, I watched as one after the other, each person agreed. I was surprised. I had chosen a structure intended to build consensus. What should I offer a group of people who already had that? What was being hidden under the surface of people’s approval? I had no choice but to listen and think at a deeper level. Otto Scharmer calls it Sensing: listening to the spoken and unspoken and seizing the opportunity for the new to emerge.

In this “sensing” space, the room felt somewhat cold and distant, and the consensus somewhat volatile and superficial. Maybe the youth didn’t want to challenge the founder out of fear of affecting their relationship, gratitude about being included, not feeling qualified to disagree, or maybe because I, a foreigner, was in the room. Sensing also revealed that the two potential peer trainers felt intimidated by the role they were being asked to step into. What could I offer to move these feelings about insecurity and fear of change into a more generative space?

I led another circle and asked: “What do you think the youth trainers need to fulfill their role to the fullest, and what can you offer to support them?” As each participant voiced what they thought the youth needed and how they could provide support, they also spoke of qualities already possessed by the youth: joy, determination, commitment, enthusiasm, willingness to learn, companionship, and respect. I watched the youth change from slumping in their chairs, to sitting tall, backs straight. Eyes went from droopy to lively. The atmosphere lightened, the smiles became abundant.

***

I’m pleased to say, that the youth trainers have now trained two groups and are confident in their abilities. “I learned so much by teaching.” One youth trainer told me this summer. “I learn from my students, every day.”

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Program Evaluation

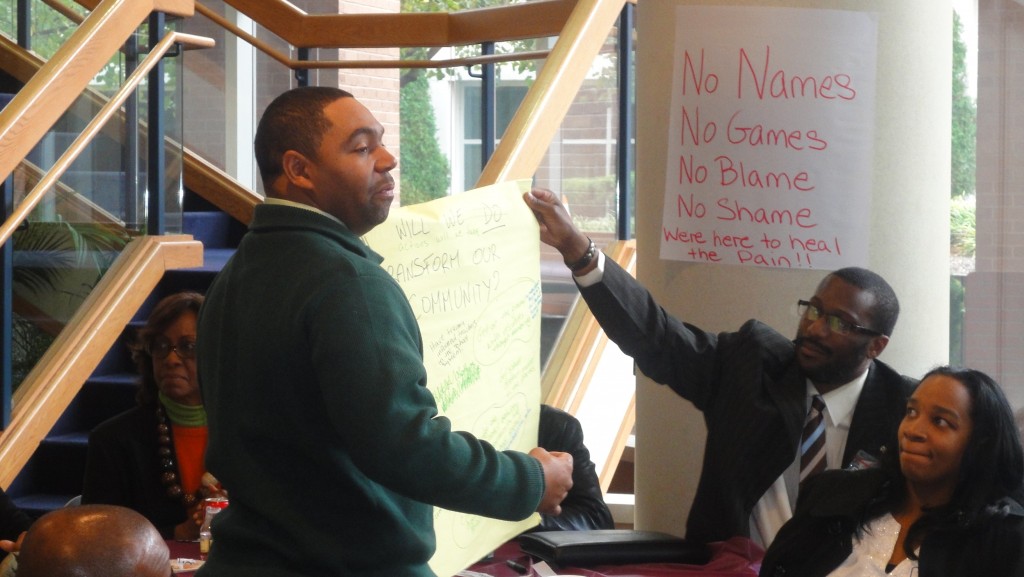

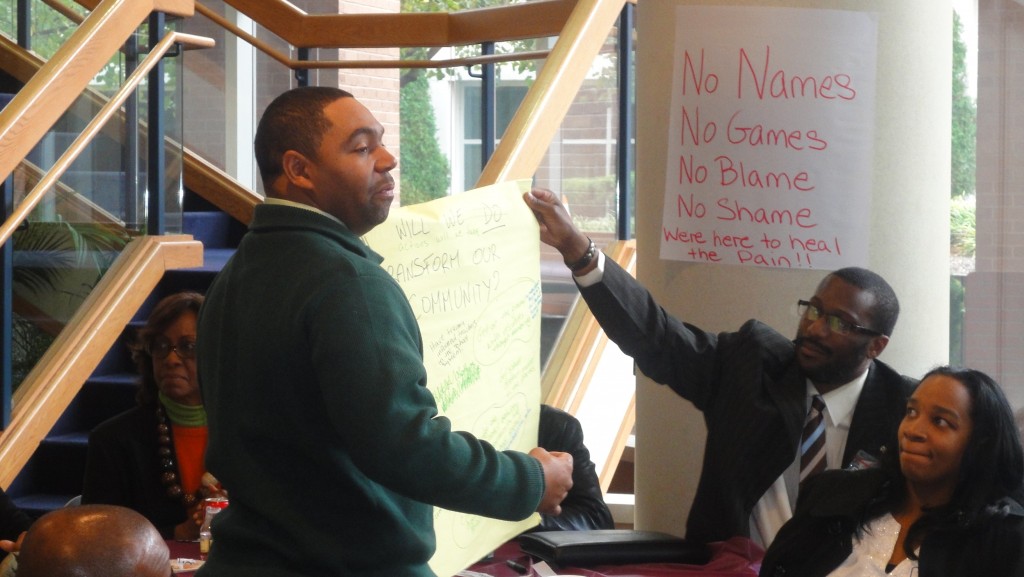

I recently was hired to help a group of people (Chester Real Change) generate a visual model that represented the transformative process they collectively experienced regarding the impact that violence had had on them.

As a participatory leadership facilitator, I worked with my client to create a structure for a retreat and questions that could meaningfully generate deep reflection. We decided we would start with personal process and then move to group work and image generation. I proposed a 20-minute individual journaling session that would encourage reflection on the following questions: What changed for you from the beginning to the end of the process? In which moment did you experience the shift? What helped the shift unfold?

In 5 minutes, participants were done and laughing and talking. Struggling to control any expressions of irritation, I asked participants to share their reflections.

“Well, I don’t like the term ‘shift’,” One participant said. “Things didn’t really shift for me. Things didn’t change; it’s just that I was having a group experience. For the first time, I got to meet other people who had to deal with violence in a different way.”

Community building in Chester, Pennsylvania

1 / 3

StartStop

“So,” I asked, “if you were to pinpoint the moment in which you felt that community, the moment in which things changed for you, when was it?”

The director of the host organization stepped in: “What I’ve learned in this process is to NOT do what you are doing, which is to contrast, simplify, and interpret other people’s answers, but to listen to different perspectives. I think she gave you the description of her experience, and you need to listen deeper and not try to change what she said.”

The handslap hurt, but was helpful and needed. I realized I had forgotten to take off my evaluator hat: I had focused on desired outcomes and pushed the conversation instead of allowing it to go where participants saw fit. Otto Scharmer in Theory U would say that I was thinking from limited past experiences instead of presencing: stepping into the possibilities of the future by sensing and connecting with it as it takes form.

Scharmer says that you sense and connect by holding an open heart and open mind. I wasn’t open enough. Generating a process for facilitation is very different than generating one for evaluation. With evaluation, you stick to a process to identify and measure desired outcomes; in facilitation, you must let go of the process and allow it to change, trusting that a vision of the future will emerge.

I was grateful for the director’s comment (and thanked him), because it allowed me to take off my evaluator hat and allow the future to take place instead of pushing and planning for it to do so. The moment in which I became aware of this I was able to hold the space for more generative listening, and I engaged participants in the active role of letting me know if the process was working for them. I checked in with participants and made many variations to our process throughout the day.

As the best meditation practices teach us, once you let go of the strong attempts to empty your mind, you may achieve that which you desire. Similarly, when I completely let go of my facilitation goal, not surprisingly, a conversation took place where we identified the image we so aspired to create.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation

On a recent evaluation and facilitation project, I came on as the new hire to a well-developed team. The client was a prestigious foundation, and it was a high stakes project for everyone involved.

I was expected to hit the ground running and had no time to get myself acquainted with the particular work style of this team. Over time, my initial discomfort increased, rather than decreased. My colleague’s management style favored attention to details over big picture thinking, and I learned from this process that I’m more of a big picture person.

My gut started to tell me we were missing something. I didn’t feel comfortable asking my busy colleagues to talk about something I couldn’t put my own finger on, though. Imagine asking a colleague: “I want to have a meeting with you, but I don’t know what it’s about!”

Instead, I retreated into a deep, self-critical mode. “My discomfort must be about my ego,” I thought. Did my ego create the struggle with my team because the management style being utilized was out of my comfort zone? Was my ego trying to push the big picture on the table at every meeting to gain control? Did I simply need to trust my colleagues more and let go?

So I tried something different. I gave my ego a good slap, and practiced letting go for the next few weeks.

Over time, the fact that a big-picture perspective was missing gave the project an unexpected jolt. After we identified a strategy to address the jolt, I found myself feeling more relaxed, and the nagging feeling was gone.

It was then that I realized that my discomfort had not been ego-driven. It was my intuition prompting me to pay attention and speak up.

Over the course of the project, I had chosen to silence my intuition, when instead I could have hosted an explorative conversation. I could have said: “You know, something in my gut tells me we’re missing something, but I can’t put my finger on it. Could we have some time, maybe just 30 minutes, to brainstorm on our overall framework to see whether my feeling is well founded?” I’m sure my teammates would have accepted the invitation.

While maintaining a practice of being aware of one’s ego getting in the way is a helpful one, I now aspire to host a balance within myself between self-critique and self-trust.

Maintaining this balance is critical self-facilitation work because both extremes –self-critique and self-trust– can strangle conversations. Both can make us get so wrapped up in our own minds that we lose touch with the needs of a group or process. We disconnect from the intelligence of our hearts, which can guide us through challenges. Hosting that balance within ourselves allows us to host it in the rooms where we carry our craft.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Uncategorized

Speaking with Radical Honesty is a relatively easy practice to preach and a really hard thing to do. I first heard the phrase a few years ago, and it lingered in my mind. Our ability to hold the HARD conversations in life is a big part of what defines us. HARD conversations are as an integral part of life as are joy and love.

I once attended a ten week course hosted by a community that is very important to me and makes me feel at home. I hated the course. It was too long, too boring, and I longed for creativity and intellectual depth, but most of all I longed for warmth and heart. The teacher was tired of teaching and it showed. Throughout the ten weeks I took on different roles. First, I challenged the teacher with hard questions that got no answers, then I withdrew, then I tried to learn more about her story and connect with her. Finally, I withdrew again. Other participants in the course were also bored, but did not speak up. The ten weeks dragged.

Baby orphan elephants hugging (Nairobi, Kenya)

1 / 2

StartStop

At the end of the ten weeks, the assistant teacher spoke to me from a place of love and Radical Honesty: “It hurt when you withdrew. It felt like you thought you knew more than me, that you were superior. I felt that I failed you, that I was not a good enough instructor for you. I wanted to give you more and couldn’t. ”

The assistant teacher’s Radical Honesty drew me in. I had to admit that I did not know how to have a Radically Honest conversation with the teachers. I didn’t know how to voice my boredom and ask questions about how we could co-create a different class. I was scared of being judged for wanting different things and seeing things differently.

Often, the things that most need to be said are hard to say and hard to hear. How you handle the elephants in a room is a big part of how you show up in a workplace.

Some people keep an elephant in its place and never mention it. They feed the elephant while denying its obvious presence, silently leaving mounds of food and milk in the middle of the room. Other times, people scream to the world that the elephant is standing right there, while everyone else around them pretends not to see it.

There is another way to handle unacknowledged tensions in a room: asking questions with curiosity and wonder. “Hmmmm,” says the wise one, “I wonder where the food that you laid at the center of the room went yesterday? It’s no longer there.” Slowly and delicately we engage with others and overcome the resistance to naming what is in the room. I did this in a final conversation with my teacher by asking her what aspect of teaching brought her enthusiasm. “I don’t know,” she answered.

It takes courage to welcome Radical Honesty as an opportunity for growth, and you’ll never know exactly how you’ll grow from it. Sometimes a relationship can stumble over a challenging conversation and shoot up afterwards like a rocket –sudden, immediate, strong, impressive.

The teacher and I never became close, but the teaching assistant and I did. In our Radically Honest conversation, we each held the best and most tender parts of ourselves.

These conversations are not for the faint of heart, and they are also not for every relationship. They take time and commitment.

Recent Comments