by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Participatory Leadership, Program Evaluation

I’ve been integrating Participatory Leadership practices with Evaluation for years now. It started simply as a way to bring two passions together. After systematic reflection, blogging, proposal writing, co-editing a journal issue (New Directions in Evaluation, Spring 2016), and teaching trainings on building the bridge between evaluation and facilitation, I have become a lot more aware of the critical importance of this bridge for evaluation practice in service to our changing world.

A drug and alcohol prevention network uses participatory leadership to help identify priority work areas in Auckland, NZ.

- Creating a Positive and Future Forming Reality. Participatory Leadership practices help shape the future in terms of possibilities and opportunities. As Gergen (2014) points out, if research does not take an active role in helping participants envision new, innovative, and positive collective realities, then our research methods only mirror back a negative view of current reality, de facto supporting the status quo. With its focus on collective intelligence, participatory innovation, emergence, shared decisions, and shared ownership, Participatory Leadership practices are future forming. They help groups identify powerful questions to inspire, move forward, and overcome challenges. I use evaluative tools to document that movement forward. I also use facilitation tools that in the Art of Hosting community are called harvesting tools (graphic recording, video recording, mind mapping, notes of conversations, doodles, post-its, etc.) to show what took place and what decisions were made.

- Local People (Stakeholders) Drive the Agenda. In most evaluations, even participatory evaluations, evaluation capacity building, and democratic evaluations, the evaluator generally decides in which phases of the evaluation process stakeholders will participate: evaluation questions, design, purpose, methodology, methods, or reporting. Participatory Leadership practices can be used to allocate more space for the needs of local people to drive the agenda of conversations that precede planning by answering the following questions: 1) What conversation does the group need to have to be strengthened in their purpose, collective work, and effectiveness? 2) How can we use the evaluation to hold the space for these inspiring conversations? 3) What evaluation and harvesting practices can we use to document these conversations?

- Building Dialogic Capacity. Participatory Leadership practices and theories help us reflect on the pitfalls of oppositional talking, or debating, and the creative power of true dialogue. We challenge participants to move beyond oppositional dialogue into deeper listening and creative conversations. In doing so, the group’s builds its capacity to engage in genuine, creative, and generative dialogue.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage in storytelling in Christ Church, NZ.

- Culturally Affirming. While there are evaluators who work all around the world in a variety of cultural contexts, the theory and practice of evaluation are still dominated by Western worldviews. For the non-believer, the evaluation language can often come across as linear, cold, distant, emotionless, complicated, rigid, and somewhat out of reach. While participatory evaluation and capacity building evaluation use activities to make evaluation more approachable, Participatory Leadership practices focus on the atmosphere we create in our meetings: a welcoming, more heartfelt environment where different cultures are welcomed and have more freedom to be who they are. I wouldn’t say that Participatory Leadership is culture-free, yet it isn’t as tightly constrained and culturally prescriptive as other approaches (timeframes are flexible, agendas shift depend on participants’ reactions, participants have space to raise their own issues or start their own conversations). There is more space for counternarratives to be told (more detail on this to follow in another blog).

- Advocate Inclusion and Involve Large Groups in the Design. Participatory evaluations typically involve small groups because many believe that the more people involved, the harder it is to reach decisions. Participatory Leadership practices enable us to work with large groups using relatively minimal resources and generate meaningful information to inform evaluation design and practice. For instance, a skilled group of facilitators can conduct a World Café or Open Space with 150 people in 2-3 hours to inform the Evaluation design. Some Democratic Evaluations also involve larger groups, because the evaluators are trained in dialogue and deliberation.

- Hosting Polarities and Power differences. In my experience, management can gatekeep and ostracize participation in decision-making more because they lack the skillset to handle opposite opinions productively than for ill intent. Participatory Leadership practices help the evaluator prepare for, plan for, and host dynamic tensions and power differences in a way that is both respectful of all individual parties and productive to the group.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage at the AEA conference in Denver, CO .

- Holding Space for Complexity. Using the Cynefin Framework as a point of reference, the comfort zone of an evaluator, generically speaking, is most likely to be the realm of the complicated. Our logic models are generally created, tested, and validated with complicated frameworks in mind: several causes generate several effects, in a mixture of linear and non-linear ways. However, the contextual factors and external factors in our logic model designs are areas of complexity that are often listed, but not deeply investigated. Participatory Leadership practices allow space for the investigation of the complex within our evaluation designs in a way that is meaningful and productive to other aspects of our work.

Our world is changing rapidly. If it is true that there is an unsustainable, self-destructive trend in our world, it is also true that there is another one: innovation, cooperation, and community-building. Participatory Leadership can bring tremendous strengths to our evaluation practices as it incorporates skills to engage groups and communities in an inspiring way around what to do with the current struggles of our world. In doing so, Participatory Leadership trains us to see the potential in the unknown, the emergent, the unclear, the out-of-control. And as long as we are dealing with human beings, the unknown, the unclear, and the unpredictable is always near. We can try to control it, just to satisfy our own compulsion and need for a security blanket. Or, we can immerse ourselves in the transformation and put our evaluation skillsets at the service of conversations that people need to have in a changing world.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Personal Leadership

If the term Emergence gives you a discomforting itch either because you don’t understand it, don’t value it, can’t work with it, or it sounds too woo woo for you, I have a fun and light suggestion that may bring your mental lightbulbs to life. Watch the animated film: Penguins of Madagascar. I’m not joking. You can watch it with your kids over the weekend, have fun, and no one will suspect you’re learning or working.

Left: The Planning Competition: Skipper the Penguin’s Plan. Right: Classified the Wolf’s Plan. (movie shots)

On the surface, it’s a story about an technologically equipped team called North Wind (NW), “saving” some penguins risking extinction. Turns out, the penguins may not need saving after all; they are not as helpless as North Wind (NW) assumed.

But it is also the story of two leaders in competition (Skipper the Penguin and Classified-NW, the Wolf) who fight to be recognized, respected, and “right” above and beyond the other within the pretext of saving the helpless. Sound familiar?

Classified is the leader of his very well-equipped, well-organized team. They look professional, impeccable, and their plans are thought-out down to the very last detail. It’s very easy to assume they are the most competent, the most prepared, the most professional.

Skipper the Penguin is instead, a leader of a team of four penguins who work with emergence. Skipper often polls his team to assess moments of crisis. When there isn’t enough time to do so, he gives directions and acts from a great deal of intuition, as do his team members. They make moment-to-moment decisions.

Both Skipper and Classified are respected within their small team. But once the two teams have same target, there’s trouble. Each leader wants to be in charge and prove their way is the only right way and the result is chaos. The conflict that ensues is one we’ve all seen. One at a time, they each fail and their teams pay the price.

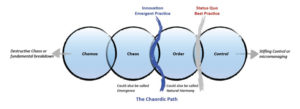

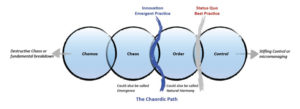

The Chaordic Path Theoretical Framework: An Illustration

When it comes to flying a plane, Skipper’s emergence tactics are not the best choice. Classified’s impeccable plan on the other hand, falls apart when unpredictably, the whole team gets trapped by eight octopi.

The story exemplifies the Chaordic Path, the creative path that emerges between chaos and order. The term Chaordic was coined by Dee Hock. In organizations, this means being able to create space for the new solutions that come about–emerge, from the combination of Chaos AND Order–combined.

I don’t want to spoil the movie for you. All I’ll say is that in the “glorious future” of our animal families, we gain an appreciation of the bravery that Emergence requires. From the competition between the two leaders, a new leader is born, who combines bravery, creativity, and analytical thinking.

I won’t say anything else for now…..but feel free to post your comments below if you have any other questions or other parallels that you notice in this movie with leadership practices and group dynamics!

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

Just before this groundbreaking week, I attended a four-day Theatre of the Oppressed training for facilitators. This was my unintentional preparation for a week in which the South Carolina shooting and less-heard burning of Black churches, the Supreme court upholding of the Affordable Care Act and Gay Marriage. Whatever side you are on, the mix of these events are making our opinions about difference in America slap us in the face.

Photo by em_diesus

We can choose to do the deep work that allyship, forgiveness, and restorative justiceentail. This work is never comfortable. When we face the beast, we often want to run away. Most often this is because we discover that beast who we hate outside of us, is also within us, we have internalized it. We are not immune of the context we grew up in. I’ve learned that I no longer do this work to help others. I do it to embrace my own humanity in how I show up for others, but also how I show up for myself.

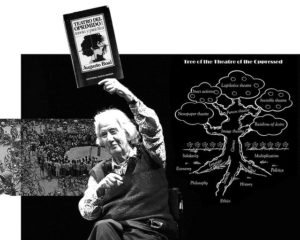

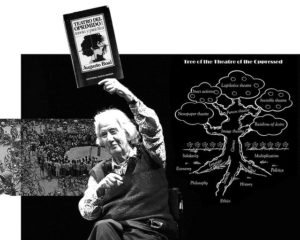

There are many different approaches to doing this “work.” One is the Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a groundbreaking way of using theatre and improvisation in groups to help people engage individually and collectively with how they have been affected by power structures and beliefs. Created by Augusto Boal, it is grounded in Paul Friere’s powerful Pedagogy of the Oppressed. By being spect-actors, simultaneously spectators and actors, participants have a chance to both reflect on a situation and offer strategies to overcome the challenges each solution presents.

I tend to take on a role in groups, one in which I challenge the group to go deeper. At times I’ve been painfully scapegoated for it. But the group in my Theatre of the Oppressed training was a singular group of people who are brave themselves and who are as passionate about facilitating conversations about power, inequity, and justice, as I am. So they welcomed my challenge and bid me higher, pushing me way out of my comfort zone.

In some small-group work, we set up a skit of a summer backyard party in which the owner, a white woman, Sally, who recently moved into the imaginary neighborhood, tells off the Black guy, Jamal, who’s lived in the neighborhood for generations, because he plays loud rap music from his car in front of her house. A friend and ally, Kate, steps in to support the Black guy and calm Sally down, but Sally is drinking. She gets louder and louder, nastier and nastier. As her sense of entitlement grows, so does her escalating rage. Here are some things she says:

“Not in my neighborhood.”

“I didn’t spend all this money to live in this neighborhood to hear that music.”

“This is why we don’t like people like you moving in.”

“What’s wrong with you people?”

“Shut that music in front of my house. This is my property.”

When Kate steps in to ask Sally to not treat her friend Jamal this way, Sally hesitates for a second, but then keeps going, even louder.

“Stop talking to me, I want the music off, NOW.”

Augusto Boal photo by LCR SAP

Kate is turned-off by the ineffectiveness of her attempt to support Jamal, she physically takes two steps back, even if she still wants to help. She doesn’t know how, the violence puts her off. Jamal is left to confront Sally. He is peaceful and brave. He offers a handshake: “I’m a neighbor, nice to meet you, can we talk about this?”

Sally barely concedes her fingertips, showing her disgust for touching him.

This was a theatre moment. But it truthfully depicts how quickly things can precipitate in our own U.S.A.

I was the one who played Sally’s role.

The instructor suggested: “Boal says there is a bit of the oppressor in all of us. I challenge you to discover what playing the oppressor will teach you.”

It has taken me two weeks to write about this powerful experience that Boal would call “the oppressor within.” The experience was as enlightening as it was horrifying. Here’s why.

- It wasn’t hard. I wanted to think of myself as such a “good person” that it would be awfully hard for me to stay in character. It wasn’t. I had a repertoire of experiences to play the role: a combination of conversations had, listened to, ways I’ve been treated, and emotional truth.

- Dismissing human beings. In Sally’s role, it wasn’t hard for me to dismiss these two human beings and anything they said to get what I wanted. What I wanted in that moment was more important than anything else. As if Jamal wasn’t a human being, he was just an obstacle to be removed.

- The ball of anger. Yelling at Jamal was like taking everything that had ever hurt me, from being made fun of in nursery school to being fired on the job, any resentment for anything I believed should not have happened to me, and channeling through, no against him. This was a spiral. Once it started, it was addictive. It was easier than I thought to let it escalate.

- The shame. After I stepped out of role, I had a deep sense of shame. I felt others more distant. Were others judging me for playing the role like I had? Were they asking themselves if this is really who I am? Is it?

- The isolation. Also after I stepped out of role, I felt so isolated, that I was questioning the foundation of my own humanity. I felt alone in the world, disconnected. I felt a sense of despair that only human contact could nurture away. John A Powell in a recent interview said “The issue of race is an issue of belonging.” In that isolation, I was terrified of not belonging anywhere. Thankfully, I know how to reach out for connection. I’ve learned to ask for help. How do the people who embody this harsh role to an extreme feel on a day-to-day basis? It brought to a tremendous sense of pity.

The oppressor in me is completely disconnected from others and my true self. The oppressor in me is judgmental, harsh, ruthless, entitled, but also isolated and terrified. The oppressor in me is my inner critic. Confronting the oppressor outside means also confronting the one within. The scope of this work is not navel-gazing, guilt, or a shallow helping others. It is: to “initiate a healing process toward freedom and justice.”

The goal of theatre of the oppressed though, is to offer strategies, not solutions. So what makes this role true for me? What part of our oppressive society have I taken in and do I play against myself and others? How do I overcome those roles?

The more I work on my within, the more I walk and work more boldy in the world.

Photo by em_diesus

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Program Evaluation

This article appeared in the American Evaluation Association’s Feminist Issues in Evaluation Interest Group’s Newsletter on July 9, 2015 and is being republished here.

In the PAGES project for Girlhub Ethiopia, in March 2014, we explored community attitudes about girls’ education. The Afar region of Ethiopia is predominantly desert; the population is predominantly Muslim and nomadic. Most Afar people live in mobile homes made of sticks, mats, and plastic covers that are gathered into a bundle when it’s time to move.

The overall evaluation was a randomized control trial that included 3000 participants. The surveys and interviews in the overall evaluation revealed that the community had very positive attitudes towards education. When asked if children were “in school” most parents and most children said yes. School enrollment is mandatory in Ethiopia.

A subset of 100 girls and 100 female caregivers participated in our exploratory study using SenseMaker’s mixed-method storytelling methodology. Grounded in complexity theory (Cynefin Framework), SenseMaker uses more indirect and complex response items to help identify contradictions and complexity.

Here are some:

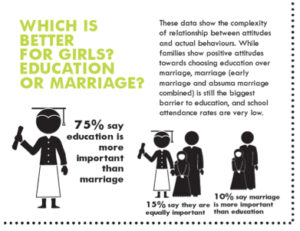

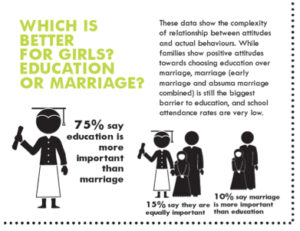

- While 75% of girls said they were “in school” only 25% attended 5 days a week.

- While 75% participants say that education is more important than marriage to improve a girls’ life, 77% of girls and 57% of caregivers say that child marriage is a barrier to girls’ education.

- While chores (which include walking 5-10 km a day to fetch water) are listed as the biggest barrier for girls’ education (84% of girls and 82% of caregivers say so). Many participants (32%) say that the family’s beliefs about education determine whether a girl goes to school.

When asked who benefits from a girls’ education, the camp is split. Some say it benefits equally the girl, the family, and the community.

Many saw it benefitting the girl first, her family at a later date, and only minimally and in the long term, the community. This perception of long-term gain over short-term gain may explain the gap between attitudes and behavior, between school enrollment and actual attendance. If you had no water to drink today, would long-term gain drive your decisions? One of the recommendations made to PAGES was to add to the school curricula topics that provide helpful information for the family and the community in the short-term, given the challenges of the Afar region.

An infographic summary of results is available online on the Fierro Consultingwebsite. The full report will be available on the Girlhub Ethiopia’s website and the Fierro Consulting website in Fall 2015.

Photo courtesy of Girlhub Ethiopia ©2013

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Inclusive Conversations

Ever feel that having a conversation in a productive way when people have different perspectives is hard work? I’ve got news for you. You’re right!

This blog is the first in a series of 13 about inclusive conversations. With three introductory blogs and ten topical blogs, along with the e-book that will compile them all, I’m focusing on ten barriers to inclusive conversations and 10 skills that can help overcome them.

What is an inclusive conversation and why do inclusive conversations matter?

Here is a beginning definition of inclusive conversations.

I see an inclusive conversation as a conversation in which differences in perspectives are leveraged as opportunities instead of threats or being ignored.

Differences in perspectives are always grounded in differences in life experiences whether they are based on gender, race, ethnicity, culture, class, location, job rank, political outlook, allegiances, hair color, or whatever other life experiences play an important role in an individual human being’s life.

Here are a few opportunities for inclusive conversations:

- Generating strategies: Someone with different life experiences from the majority is invited to offer unique insights to understand the reaction of a wider audience;

- In-group perceptions of other people: People from one group have a conversation about a person or group with a different set of life experiences;

- Dissipating tension and staying engaged: Tensions build because of different perspectives, where the differences risk shutting down the conversation, e.g. agreeing to disagree;

- Getting feedback: Getting genuine feedback on your work from someone who you know will have different view.

Engaging differences as building blocks instead of walls takes overcoming internal and external barriers and exercising certain muscles.

In this blog series there will be 10 skills that will help you increase your capacity to have inclusive conversations. I will also tell you stories about how they I used them.

But before we get to skills, let’s check our assumptions. Why is inclusion important? Why should we care? That’s the topic of my next blog.

Recent Comments