by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Facilitation

On a recent work trip to Ethiopia, I led and facilitated a group of 15 researchers collecting stories about adolescent girls for Girl Effect with SART, an Ethiopian Research company. We followed a BBC crew showing a documentary about stories of Ethiopian girls.

I used participatory leadership practices to build the team’s spirit and commitment to their work. For the team to take ownership of the process, they needed to understand the importance of women’s experiences. What better way for this to occur than on our own team? But in the meetings, the women were quiet.

A researcher collects a young storyteller’s story

1 / 4

StartStop

During the first two days of working together, I was frustrated. Everything I learned about facilitation was not working. One-on-one informal conversations flowed, but once the team was in a meeting, my opening question would be met with silence. “What are you learning about this community?” “What would you like to share about your experience today?” “Did anything stand out?” On the third day, the coordinator approached me and said: “Dr. Rita, the questions you ask, they’re too ….they’re too hard to answer. That’s why we’re quiet. We’re Ethiopian. We don’t like to break the ice. We prefer silence.”

I asked him to guide me in ways to overcome these challenges, and I learned to begin with more concrete questions (“Who facilitated groups today?” “Were young girls more responsive in smaller groups?” “Were girls looking for validation from facilitators?”). I also asked team members to respond to a question by going around in a circle, which made it easier for people to speak up, as their turn was designated and expected.

This worked well in debriefing the research process, but didn’t address team members’ emotional needs. Though the project was short, the two weeks of data collection were very intense ones for the researchers; the more they collected stories, the more stories of physical violence against children, rape, hunger, and tremendous poverty emerged. I could see the team becoming sad, worn out, and overwhelmed. I could sense the team spirit wavering.

I wanted to offer my support, yet, as a western researcher, it was unlikely that they would come to me. A strong sense of reserve and dignity kept team members from sharing their challenges. Still, I continued to hold space for the hard conversations in our meetings. At each meeting, I asked if there was discomfort, and I renewed my availability for anyone who needed me. “Are there any stories that were hard to hear?” “How do you feel collecting these stories?” All questions were met with silence, yet I was no longer worried. I could sense that spirits were not as heavy. Just by having the option to talk, members were lightening up.

Later, I asked the coordinator if team members ever talked about their experiences AFTER our meetings: “Yes, last night we did, and for quite a while.” “Good,” I said, “I don’t have to hear the conversation. I just want it to take place. As long as you go to each other about how this work makes you feel so you don’t burn out.”

I was happy hosting the silence that generated later conversations. I didn’t need to hear the whole conversation. Sometimes all a facilitator can do is host the silence that plants the seed for conversations to grow in better-suited contexts. English was not my researchers’ first language, and I was not a person from their culture. If the conversation didn’t take place in my presence it didn’t matter.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Facilitation

In 2012, I hosted a retreat for Kito International an organization in Nairobi, Kenya that trains street youth to establish their own businesses and move towards self-sufficiency. The founder Wiclif Otieno is an ex-street youth himself. In a country with a 75% unemployment rate for people ages 18-35, it is a painful truth that 300,000 youth live on the street.

Our purpose for the day was to envision the best possible future for the Kawangware community of Kito’s site and to identify ways to move in that direction.

The founder also wanted the organization to transition to peer-training by inviting two youth who completed the program to train other youth. We had a morning World Café with the guiding question: “What can we envision for Kawangware?”, a teach-in on the Chaordic Stepping Stones, an afternoonOpen Space with a guiding question: “What can we do together that we can’t do alone?”, and a Circle Council intended to facilitate making a decision about peer-training.

In a Circle Council, Circle Practice is used to make decisions by: 1) One member proposing a decision needing to be made; 2) Each member speaking their opinion and feelings about the decision; 3) Members speaking up on what is clear to them; 4) Creating a set of options; 5) Voting on the options; and 6) Building consensus by working with and modifying the most-supported option.

Circle Process in the Kito International home office and workshop site in Nairobi, Ken

1 / 3

StartStop

I chose to facilitate this decision-making structure because I was told there was disagreement among Kito’s stakeholders. I hoped that new, composite solutions would emerge via the overt expression of different opinions in the group.

After the founder presented the decision to participants, however, I watched as one after the other, each person agreed. I was surprised. I had chosen a structure intended to build consensus. What should I offer a group of people who already had that? What was being hidden under the surface of people’s approval? I had no choice but to listen and think at a deeper level. Otto Scharmer calls it Sensing: listening to the spoken and unspoken and seizing the opportunity for the new to emerge.

In this “sensing” space, the room felt somewhat cold and distant, and the consensus somewhat volatile and superficial. Maybe the youth didn’t want to challenge the founder out of fear of affecting their relationship, gratitude about being included, not feeling qualified to disagree, or maybe because I, a foreigner, was in the room. Sensing also revealed that the two potential peer trainers felt intimidated by the role they were being asked to step into. What could I offer to move these feelings about insecurity and fear of change into a more generative space?

I led another circle and asked: “What do you think the youth trainers need to fulfill their role to the fullest, and what can you offer to support them?” As each participant voiced what they thought the youth needed and how they could provide support, they also spoke of qualities already possessed by the youth: joy, determination, commitment, enthusiasm, willingness to learn, companionship, and respect. I watched the youth change from slumping in their chairs, to sitting tall, backs straight. Eyes went from droopy to lively. The atmosphere lightened, the smiles became abundant.

***

I’m pleased to say, that the youth trainers have now trained two groups and are confident in their abilities. “I learned so much by teaching.” One youth trainer told me this summer. “I learn from my students, every day.”

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Program Evaluation

This article appeared in the American Evaluation Association’s Feminist Issues in Evaluation Interest Group’s Newsletter on July 9, 2015 and is being republished here.

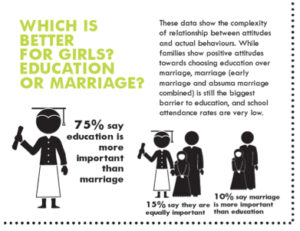

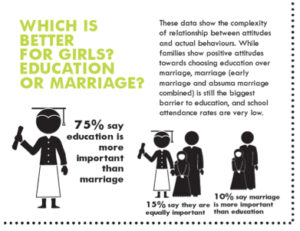

In the PAGES project for Girlhub Ethiopia, in March 2014, we explored community attitudes about girls’ education. The Afar region of Ethiopia is predominantly desert; the population is predominantly Muslim and nomadic. Most Afar people live in mobile homes made of sticks, mats, and plastic covers that are gathered into a bundle when it’s time to move.

The overall evaluation was a randomized control trial that included 3000 participants. The surveys and interviews in the overall evaluation revealed that the community had very positive attitudes towards education. When asked if children were “in school” most parents and most children said yes. School enrollment is mandatory in Ethiopia.

A subset of 100 girls and 100 female caregivers participated in our exploratory study using SenseMaker’s mixed-method storytelling methodology. Grounded in complexity theory (Cynefin Framework), SenseMaker uses more indirect and complex response items to help identify contradictions and complexity.

Here are some:

- While 75% of girls said they were “in school” only 25% attended 5 days a week.

- While 75% participants say that education is more important than marriage to improve a girls’ life, 77% of girls and 57% of caregivers say that child marriage is a barrier to girls’ education.

- While chores (which include walking 5-10 km a day to fetch water) are listed as the biggest barrier for girls’ education (84% of girls and 82% of caregivers say so). Many participants (32%) say that the family’s beliefs about education determine whether a girl goes to school.

When asked who benefits from a girls’ education, the camp is split. Some say it benefits equally the girl, the family, and the community.

Many saw it benefitting the girl first, her family at a later date, and only minimally and in the long term, the community. This perception of long-term gain over short-term gain may explain the gap between attitudes and behavior, between school enrollment and actual attendance. If you had no water to drink today, would long-term gain drive your decisions? One of the recommendations made to PAGES was to add to the school curricula topics that provide helpful information for the family and the community in the short-term, given the challenges of the Afar region.

An infographic summary of results is available online on the Fierro Consultingwebsite. The full report will be available on the Girlhub Ethiopia’s website and the Fierro Consulting website in Fall 2015.

Photo courtesy of Girlhub Ethiopia ©2013

Recent Comments