by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

Southern Italy is not the first place in the world where most people would turn their attention to when they think about oppression. My passion for understanding privilege and oppression in the United States and my choice to learn from African American present and past history is often puzzling to those who cannot see the link.

Ancient Norman Castle of Apice, Benevento.

1 / 6

StartStop

Well, over many centuries Southern Italy was invaded over and over again by Moors, Romans, Vandals, Normans, Slavs, Visigoths, the French, and Spaniards. This makes us a surviving people, and that’s why Italy has so many castles, arches, and other edifices – parting gifts from past invaders.

It took the Romans 53 years to get my people, the Samnites, to submit to their will. The Italian national unification movement, which created the nation of Italy in 1861, deposed our beloved and trusted southern Italian leader Garibaldi, as the northern industrial forces feared that the southern Italian agricultural workers would demand a social revolution and redistribution of land. This redistribution of land has been sought after since the Roman Empire, and is still relevant to the North-South conflict today.

Sound familiar?

There are three common internalized responses to oppression I hear a lot both in my small Southern Italian hometown of Benevento and in the predominantly Black neighborhood I live in, in the USA:

- “They won’t let us do anything.”

- “They’re jealous; as soon as you try to rise they will bring you down.”

- “You can’t do that.” (“It” can be anything from creating a workshop to a radical shift in political representation.)

These three common responses, I believe, are a strong indicator of a people who have never felt represented by their government and who have gotten accustomed to being repressed instead of encouraged.

This defeatist thinking is a hindrance to our work of building collective action. Overcoming it isn’t easy.

Carter G. Woodson, a phenomenal African American historian and thinker said it most effectively:

“When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his ‘proper place’ and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.”

I’ve done a great deal of inner-awareness work in the past years to overcome my self-sabotage and negative thinking mechanisms. I have made some progress, though I’m certainly not done. Being in Italy during the holiday season with my family while I offered seminars and workshops reminded me on a daily basis how the ongoing imposition of limiting beliefs is a way to keep oppressed people “in their place” and off the radar of innovation and world change.

It reminds me of how far I’ve come, and how much farther I need to go for positive thinking to become a default for me.

Breaking away and living in other countries may have allowed me to escape the hypnotic negative thinking of my people. I’m beginning to think that specific vibrations of internalized oppression are peculiar to a land and people, and it may be easier to live and operate within the context of oppression of a people other than one’s own. When I am in the USA, the pain I feel isn’t as paralyzing, internalized, and self-inflicted as when I’m in Benevento.

This reflection is helping me mitigate the judgment I feel about my own people that underlies my irritation with them. Reflecting on my peculiar positionality within my culture is helping me be a more compassionate daughter, role model for my cousins, and consultant in the work I am doing in Italy.

When I am in Italy and as I work with oppressed peoples around the world, I practice:

- Patience, as I recognize that it is my privilege of being able to travel that has affected the way I look at my own oppressed reality when I’m up close;

- Gratitude, as I appreciate the opportunities I’ve had to break away and live differently; and

- Compassion towards those who are still stuck in a negative-thinking cycle.

- Another view from my grandparents’ farm in Apice, the trees on the right and bordering the river.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

In the face of the media attention to police brutality and the failure of juries to indict the officers who pulled the triggers in the killings on Michael Brown and Eric Gardner, I cannot be silent. The issues are not new, but the media has now decided that they are newsworthy, so we are now inundated. As a white anti-racist ally, I feel the need to speak up on one aspect of white supremacy and the way it plays out in the United States against Black and brown people.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

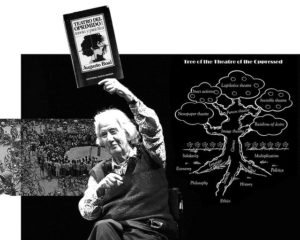

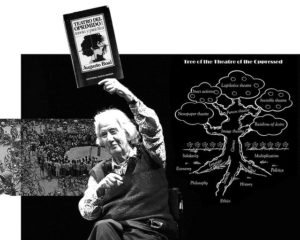

Just before this groundbreaking week, I attended a four-day Theatre of the Oppressed training for facilitators. This was my unintentional preparation for a week in which the South Carolina shooting and less-heard burning of Black churches, the Supreme court upholding of the Affordable Care Act and Gay Marriage. Whatever side you are on, the mix of these events are making our opinions about difference in America slap us in the face.

Photo by em_diesus

We can choose to do the deep work that allyship, forgiveness, and restorative justiceentail. This work is never comfortable. When we face the beast, we often want to run away. Most often this is because we discover that beast who we hate outside of us, is also within us, we have internalized it. We are not immune of the context we grew up in. I’ve learned that I no longer do this work to help others. I do it to embrace my own humanity in how I show up for others, but also how I show up for myself.

There are many different approaches to doing this “work.” One is the Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a groundbreaking way of using theatre and improvisation in groups to help people engage individually and collectively with how they have been affected by power structures and beliefs. Created by Augusto Boal, it is grounded in Paul Friere’s powerful Pedagogy of the Oppressed. By being spect-actors, simultaneously spectators and actors, participants have a chance to both reflect on a situation and offer strategies to overcome the challenges each solution presents.

I tend to take on a role in groups, one in which I challenge the group to go deeper. At times I’ve been painfully scapegoated for it. But the group in my Theatre of the Oppressed training was a singular group of people who are brave themselves and who are as passionate about facilitating conversations about power, inequity, and justice, as I am. So they welcomed my challenge and bid me higher, pushing me way out of my comfort zone.

In some small-group work, we set up a skit of a summer backyard party in which the owner, a white woman, Sally, who recently moved into the imaginary neighborhood, tells off the Black guy, Jamal, who’s lived in the neighborhood for generations, because he plays loud rap music from his car in front of her house. A friend and ally, Kate, steps in to support the Black guy and calm Sally down, but Sally is drinking. She gets louder and louder, nastier and nastier. As her sense of entitlement grows, so does her escalating rage. Here are some things she says:

“Not in my neighborhood.”

“I didn’t spend all this money to live in this neighborhood to hear that music.”

“This is why we don’t like people like you moving in.”

“What’s wrong with you people?”

“Shut that music in front of my house. This is my property.”

When Kate steps in to ask Sally to not treat her friend Jamal this way, Sally hesitates for a second, but then keeps going, even louder.

“Stop talking to me, I want the music off, NOW.”

Augusto Boal photo by LCR SAP

Kate is turned-off by the ineffectiveness of her attempt to support Jamal, she physically takes two steps back, even if she still wants to help. She doesn’t know how, the violence puts her off. Jamal is left to confront Sally. He is peaceful and brave. He offers a handshake: “I’m a neighbor, nice to meet you, can we talk about this?”

Sally barely concedes her fingertips, showing her disgust for touching him.

This was a theatre moment. But it truthfully depicts how quickly things can precipitate in our own U.S.A.

I was the one who played Sally’s role.

The instructor suggested: “Boal says there is a bit of the oppressor in all of us. I challenge you to discover what playing the oppressor will teach you.”

It has taken me two weeks to write about this powerful experience that Boal would call “the oppressor within.” The experience was as enlightening as it was horrifying. Here’s why.

- It wasn’t hard. I wanted to think of myself as such a “good person” that it would be awfully hard for me to stay in character. It wasn’t. I had a repertoire of experiences to play the role: a combination of conversations had, listened to, ways I’ve been treated, and emotional truth.

- Dismissing human beings. In Sally’s role, it wasn’t hard for me to dismiss these two human beings and anything they said to get what I wanted. What I wanted in that moment was more important than anything else. As if Jamal wasn’t a human being, he was just an obstacle to be removed.

- The ball of anger. Yelling at Jamal was like taking everything that had ever hurt me, from being made fun of in nursery school to being fired on the job, any resentment for anything I believed should not have happened to me, and channeling through, no against him. This was a spiral. Once it started, it was addictive. It was easier than I thought to let it escalate.

- The shame. After I stepped out of role, I had a deep sense of shame. I felt others more distant. Were others judging me for playing the role like I had? Were they asking themselves if this is really who I am? Is it?

- The isolation. Also after I stepped out of role, I felt so isolated, that I was questioning the foundation of my own humanity. I felt alone in the world, disconnected. I felt a sense of despair that only human contact could nurture away. John A Powell in a recent interview said “The issue of race is an issue of belonging.” In that isolation, I was terrified of not belonging anywhere. Thankfully, I know how to reach out for connection. I’ve learned to ask for help. How do the people who embody this harsh role to an extreme feel on a day-to-day basis? It brought to a tremendous sense of pity.

The oppressor in me is completely disconnected from others and my true self. The oppressor in me is judgmental, harsh, ruthless, entitled, but also isolated and terrified. The oppressor in me is my inner critic. Confronting the oppressor outside means also confronting the one within. The scope of this work is not navel-gazing, guilt, or a shallow helping others. It is: to “initiate a healing process toward freedom and justice.”

The goal of theatre of the oppressed though, is to offer strategies, not solutions. So what makes this role true for me? What part of our oppressive society have I taken in and do I play against myself and others? How do I overcome those roles?

The more I work on my within, the more I walk and work more boldy in the world.

Photo by em_diesus

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Inclusive Conversations, Uncategorized

Do your conversations these days feel like black holes of despair that transform even the sweetest of donuts into booger-tasting jelly beans? If most conversations you have about these crazy primaries end up in fights and go nowhere, tip #4 is for you. Inclusive conversations occur when differences are seen as a resource, not a threat. Previous tips included preparing the conversation, choosing when and where to invest your energy, opening the door to the conversation and making allies. Today’s tip is more about the actual conversation. Tip #4: No matter how insane you think people are to think the way they do, don’t beat them down with what you know, try to pause, and meet them where they are, instead. But before I explain what I mean by: “meet people where they are,” here’s a little story for you.

Sunday dinner, with my family in Italy and we’re discussing child prostitution. I was probably 20 years old. Yes, in my family this is what we talked about over Sunday dinner, along with everything else controversial, like war, politics, and inevitably, the corruption of the Catholic Church. The final cherry on the cake? The ethics and moral stature of our local priest. And this is where I got my Italian equivalent to what in the United States would be “debate team” training.

Here were our rules:

1) To get the stage, you had to yell louder and gesticulate bigger than everyone else.

2) Once you had the stage, you had 5-10 seconds to make your opening statement.

3) If your opening statement was persuasive, you could keep the stage for another minute, but only if you didn’t get distracted by the five people who were revving up their motors to jump in.

4) If your opening statement was weak, you would lose the stage.

5) If you paused, you’d lose the stage.

6) If you stuttered, you’d lose the stage.

7) If you had the stage for a whole minute, or two (which meant you were a pro) you had to have a final punchline to end your point to win.

8) If you lost, someone would interrupt you.

9) If you won, someone would interrupt you.

Brutal rules, I know. It was our bonding time. Bonding through fire. Our Sunday dinners were notorious for being loud. Even with the doors closed, neighbors on the street could hear us arguing. And Grandmom’s (Nonna’s) house is an earthquake-proof cement house in the open country-side and the street was a quarter a mile away. The men joked that they needed a traffic light to get a word in edgewise. We are a determined bunch of folks. We could run you down with words, any day, anytime of the week, just to be right. With this kind of training, I’m sure you’re not surprised that conflict in my family is an everyday affair.

Hot peppers (that my grandmother planted) in front of her house in the countryside. The road borders the property. The houses in the distance are on that road.

But back to the child prostitution dinner. “You have to persecute the men, because the men are the clients, and without them there would be no…” my aunt yells. “Go after the traffickers, you know the mafia is allied with those crappy politicia…” my other aunt interrupts. “It’s all the priest’s fault”, my uncle says, just to instigate the crowd. This is 15 years before the catholic sexual abuse scandals. The men in my family blame priests for everything. It is their weekly excuse for sleeping in on a Sunday morning instead of accompanying their wives to church.

An uncle who has been quiet so far and really hates the exponential volume of these conversations, finally screams: “What the hell do we care? Really? This doesn’t affect us!” Perhaps this was an ill attempt to quiet things down but I was livid.

“It’s that type of not-giving-a-damn-attitude that puts girls at constant risk…” I yelled. I listed every study on violence against women I could think of. I kept the stage for a whole two minutes. My heart was pounding as I was yelling at the top of my lungs. And then my last fatal blow:

“Let’s see if you care if it happens to your own daughter.” He was immediately offended and shut down. He got up and may have gone to the bathroom. Everyone else got up to clear the table. We dispersed. We moved on to talk about the mafia and the politicians’ role in everything that is wrong with our country. I’m thankful for my brother who said to me that day: “You’re right and you make good points, but your tone is so condescending no one will ever listen to you.”

The view of my grandparents’ land and tobacco fields.

A few years later, someone told me something very similar. We were having dinner at my place in Rome, with some of my African friends. We had a fiery conversation about the United States’ international imperialism. A dear friend said to me: “You know more than most people do about this stuff, but the way you talk, you push away people who could be allies, instead of helping them get curious to find out more.” That’s when it finally hit me. No one listens to what we say when how we say it makes them feel inferior.

After six years of college in Italy and six years of grad school in the United States studying the history of racism, discrimination, and exclusion all around the world, I had more material that most to offer a great, easy to win debate. Academia taught me to not win a debate by interrupting, but with logic: name the assumption your opposition is working from, display ample historical evidence that proves those assumptions to be wrong historically, move to how the historical evidence lives on today. Propose a solution. Final punch. It was a different tactic, but it created the same effect. There is a winner and a loser.

We are taught to debate this way in the academic world, it helps us establish credibility, prove we are qualified and gain self-confidence in what we know. But the systematic beating people down with evidence is not effective at helping people see another point of view or at making allies. Both parties in the conversation eventually walk away empty. The “loser” walks away feeling horrible about themselves. They also walk away feeling horrible about the world we live in. This person’s curiosity is not stimulated. The apparent winner may feel an ego boost at first, but eventually feels disconnected and alone, depleted by the conversation too.

Great teachers know that they cannot teach a student unless they know first, what the student already knows. New knowledge depends on pre-existing knowledge. Communication specialists will tell you that that unless you know what your audience cares about, you cannot communicate effectively with them.

So for today’s tip, instead of beating people down with the knowledge you have, try meeting people where they are. This expression is common so here are four ways I’ve learned to do this that I recommend:

- Find out what the person’s current knowledge is on the topic.

- Find out what the person cares about in other aspects of their life.

- Give up any false sense of superiority and talk to them as peers.

- Prioritize the message with very few points and relatable examples.

- Relate your key points to the topics the other person cares about.

- Ask questions, before, during, and after. The conversation is not over once you make your point. There is no touchdown scoreboard.

- No matter how much you think you already know, make sure you learn something from the other person too.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Inclusive Conversations

When you take a stand, it doesn’t have to be you against the world. Taking a stand can also inspire a group to be the best it can be.

Until now, all the tips on inclusive conversations were about being receptive, asking questions, and listening. Today’s tip switches gears: it’s about taking a clear stand in the presence of flawed process.

Some years ago, I was a member of a committee in a strategic planning process for a larger organization. As is typical in strategic planning, the committee brainstormed goals, prioritized them, and then asked the organization’s membership to vote on them. One of the goals—which I had proposed—was to increase the diversity of our membership, which was predominantly white. Once the wider membership voted on the goals, the diversity goal received fewer votes. Only 60% of the membership voted for more diversity versus the 70% or higher approval of the highest-ranking goals. I realized that the process itself was flawed. The people who most cared about diversity were not present in the organization, therefore could not vote.

In our recent presidential primaries, candidate Bernie Sanders has taken a stand calling out the flawed process.According to a recent Reuters/Ipsos poll, fifty-percent of Americans agree with him and two-thirds want to see the process changed.

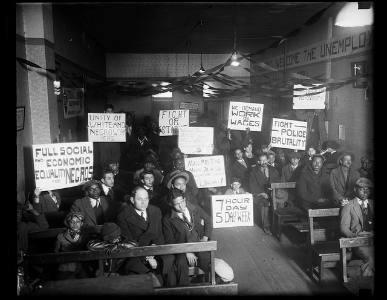

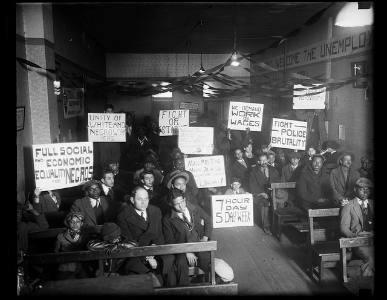

Unemployment rally at local Communist Party on March 5, 1930 to advocate for better labor conditions

As a member of the committee, I chose to take a stand.

“Given our predominantly white membership,” I said to the committee, “I argue that 60% is a high percentage, even if it is not the highest. If we had waited for any social equality goal to be voted upon by a white majority, our country would still be under legal segregation. Majority rule is not an appropriate process for choosing to increase diversity, because, many who might benefit are excluded from our membership and do not have the chance to vote.”

“But what benefits does diversity offer our whole membership?” someone asked. This is such a common question. The hidden privilege behind this question used to infuriate me because it assumes that the majority has to benefit from any action before it gets approved. It basically means “what do I get out of this?” The question no longer infuriates me. I prepare myself for the answer, before it’s even asked.

“There’s an abundance of research about how diversity improves the way people think, helping them think more deeply and creatively. We have much to benefit. I also suggest we keep diversity as a goal to choose, as an organization, the higher moral ground. Let us choose to be intentionally inclusive instead of passively exclusive.”

It worked. The goal was included in the strategic plan.

We Can Do It!’ World War 2 poster boosting morale of American women contributing to the war effort created by J. Howard Miller in 1942.

Then we recognized, like many organizations, that we didn’t really know what we were doing to be exclusive. The first objective became to find out why and build partnerships with other, more diverse organizations to grow a more inclusive membership. And it’s working. There is now a committee of people working specifically on the goal. I’ve drifted away from the work, taken by other priorities, but the work is continuing.

But before taking a stand, consider the following reflections:

- Check your motives. Are you doing this just to be “right”? What do you want to achieve and for whom?

- Check your morale and mental state. Taking a stand can have a negative effect on you. Are you in the best emotional and mental space to take this on?

- Check your allies. Are there people in the group you can reach out to support you? Check Tip 3 on the risks of not doing this.

- Check the assumptions. Are there assumptions that need to be named to make a more persuasive stance?

- Check the benefits to your audience. What does your audience get out of supporting your stance? Get clear about this before you speak up.

- Check your patience. Sometimes pushing too hard can have the opposite effect. Make sure to include patience and pauses in your plan. Oftentimes, a pause can build support because people have a chance to reflect.

- Check your learning. Try to not shut down when you take a stand. As for any other conversation, keep asking questions and learning from the perspectives of others in the group. The more you listen to others, the more likely you are to be listened to.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Racism, Uncategorized

African American people taught me how to live well, at peace, while feeling like a fish out of water. It hurts to watch how many people, and our media, assume that violence is norm in Black culture.

By the standards of most Americans I am an incredibly weird person. I am an Italian American woman who spent seven years studying African American culture in college, first for a Master’s in Sociology, then a PhD in African American studies. I left a life in Rome, Italy, the eternal city, to study in Philadelphia. I wish I could make a collage with the look on people’s faces, of all colors, when I tell them what I just told you.

I studied to end injustice, but I also studied to make peace with my own dual Italian American cultural heritage. I felt at odds in my own skin.

In those seven years, I did a lot more than study. I grew up, too. The journey started at 23. I got my PhD at 30. And in those seven years, I met two women, who led me, taught me, assisted me, held me, and walked with me in the path to becoming a woman. Both of these women are Black. So I joke at times that I’m an Italian American raised by Black women. Without these women, I could not be who I am. They taught me to love myself unconditionally, forgive myself, express myself, express my art, stand and walk in the world, while never fitting in.

It’s been ten years since the PhD and I’ve continued to grow. I’ve continued to listen and learn about Black folks in America. And I feel that I understand now that while my mentors are phenomenal individuals, their lessons were cultural, from a collective experience. They taught me some of what their families had taught them: how to survive in the face of incredible adversity.

I’ve reached the conclusion that Black people are the ethical anchor of our country. Because of ongoing discrimination, in housing, education, voting, employment, health, and the criminal justice system, Black folks have needed to dig deeper into their humanity, their resources, their talents, their networks, than anyone else in order to survive America. Of course, many other people of color have experienced these challenges, too. Over the years, I felt an affinity for African American culture that made me want to know more.

To me, the reason why Black folks dominate the art world is because they’ve needed to use art to express their deepest pain, injustice, and emotions. From old spirituals to blues, Nina Simone to Miles Davis, India Arie to The Roots, art has become a vehicle for humanity, for expressing humanness, aliveness. Playing hearts, souls, and pain through the beat of drums, voices, guitars, trumpets, saxes, and basses.

I’ve traveled the world. Yet in my experiences, Black folk in America, as a people, have deeper compassions, feelings, and forgiveness than any other culture I know. They have been trying to forgive white folk for hundreds of years of injustice. They’ve been nurturing community and organizing peacefully as long as they’ve been on this land.

Dressed in Sunday’s Best

I know most white folks are scared that Black folk will become violent and attempt to turn over the social order and be on top. This has not happened and will not happen because Black folk will not do to whites what we did to them because the majority of Black folk have worked hard and work hard every day to be productive, patient, and loving. To believe that a better world is possible. To not judge the few for the actions of the many.

Spirituality upholds Black folk. The strong connection to each other, to God, to a higher power, to prayer, to whatever you want to call it, that connection has kept Black folk alive and positive for centuries. Have you noticed how in Black neighborhoods there is a church every few feet? Learning to elevate one’s heart, mind, and soul above limiting circumstances. Moving mountains with kindness. Drawing strength, never easily, from the bowels of existence, which in the words of W.E.B. DuBois “dogged strength alone keeps from being torn asunder.”

Most of us white folk are so attached to having things our way that we lack the same capacity to be positive through hardship, love through challenges, patient when times or tough, and to express when we’re in pain. Think how much you would love your neighbor if you knew that their great-grandfather had raped your great-grandmother, during slavery, and that your neighbor’s family has forgotten this, but yours has not.

How much would you love your neighbor if your neighbor’s brother also worked for the police force that killed your dad when you were 5? And your brother when he was 15, and your best friend when he was 20?

Now add on the fact that your neighbor also has better access to better healthcare, education, employment, housing, legal and political representation than you. Would you even try to love your neighbor? Would your protests against inferior access to healthcare, education, employment, and legal representation be peaceful?

It is this ability to connect with humanity, with humanness that causes white folks to be so enamored with Black music, culture, food, fashion. We white folks reach out to Blackness to connect with our own humanity.

A rally attendee on a scooter holds a sign reading Black Lives Matter at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco.

This is also why I believe when we white folk say something we know is questionable in a group conversation, we look at Black folk for a reaction. Deep down, we know Black folk are the measure of our humanity. We know they are the measure of whether what we said was fucked up.

Most Black folks are already modeling humanness with incredible compassion and grace. But we cannot demand they do what we as a country, don’t do.

Our country is a ship in the waters of ethical confusion. Black folk are the anchor. They anchor us with the deepest and most profound parts of our country’s humanity: our ability to love, to create, to forgive, to connect, to organize for justice.

The waters are getting choppy. And the captain–society, the government, white folks, our institutions–is revving the motor. How can we expect the anchor to keep the ship grounded?

Every murder is an acceleration. Every child charged as an adult is an acceleration. Every bargain deal accepted by an innocent man is an acceleration. Every person in prison because they cannot pay a fine is an acceleration. The ship cannot stay still if the acceleration continues.

It is unjust to expect Black folk to anchor our collective ship.

The chain linking the anchor to the ship is breaking.

So whomever you are, wake up. Find your humanity. Choose whether you want to keep revving the motor on our ship or demand it stop. Get involved to change the conditions that are generating this insane acceleration. Join an organization, that suits you, that is working to slow it down. There are many.

Langston Hughes described it well when he wrote:

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?…

Or does it Explode?”

Langston Hughes

***

I wrote this in response to the killings of Philando Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling by the hands of police officers. May your souls rest in peace. May your lives not be ended in vain.

Five hours after I wrote this, Micah Xavier Johnson, a Black man who had served in the United States Army in Afghanistan, earning several medals, shot 11 white police officers, killing five, in Dallas, TX.

Images:

Dressed in Sunday’s Best by Su-Chan

https://www.flickr.com/photos/su-chan/

A rally attendee on a scooter holds a sign reading Black Lives Matter at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco.

By Pax Ahimsa Gethen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50063410

Recent Comments