by Rita Fierro | Dec 5, 2019 | Facilitation, Inclusive Conversations, Participatory Leadership, Racism, Uncategorized

On Wednesday, we found out that Donald J Trump is our president-elect. I spent the day grieving for what I thought the next ten years of my life would look like, for me and the children I’d like to bring into the world. Outrage got him elected. Outrage now grows in those of us who have begun marching. I spent the campaign season reassuring myself that 60 years of desegregation, activism, and coalition building could not have happened in vain. That we were a better people, a more united people, than it seemed. That the violence, the hate, was the minority of us, and Trump’s campaign would become just a bad dream. I was wrong.

The violence is rising.

When I guide groups through frustration and outrage, I say it’s time to tend to the margins. In this case, the margins have become 50% of the popular vote.

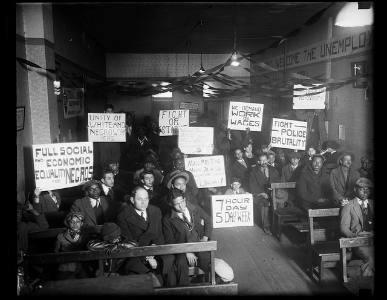

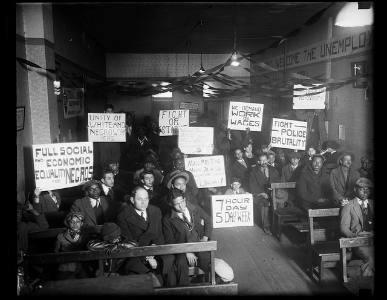

For our series on inclusive conversations (conversations where differences are seen as an opportunity, not a threat), tip #7: Look for wisdom in the outrage.

I support groups of people to agree on a future direction, even large groups of people.

It’s a process that sometimes happens quickly and sometimes takes months. In each and every process, there is always a moment, when the frustration and the anger turn up. Often, I get blamed.

“Rita, you are not the right person to do this.”

“Rita, I have no idea what you want from us.”

“Rita, I’m lost.”

“Rita, you were too ‘woo woo’ in that meeting, Black folk do healing differently.”

“Rita, you are blaming me for your lack of skills.”

I said I support groups towards a common decision, I didn’t say it was easy. Often, the frustration gets directed at me. Things get delicate.

It is very hard not to react when attacked. It’s extremely hard to keep listening when I disagree with the accusations and my own emotions are triggered. But I know from experience that when the frustration shows up, it’s time to tend to the margins.

First, this means taking the time to listen to the perspective of the person/people who has/have a different opinion and really, really, taking the time to understand it. That process can take a phone call, two, or three, a lunch or more. I try my best to not take personally whatever the accusation is, but to truly listen to understand.

Second, when I’m alone again, I lick my wounds. Again, I didn’t say it was easy. I didn’t say the accusations don’t hurt. And some days are better than others. I can’t deeply listen to others unless I listen deeply to myself. I spend time thinking about how I was affected by the interactions. Did the accusations get to me? Why? Are they a projection of my own thoughts about myself?

Third, I do some thinking and processing about the conversations I had. I may call a colleague for insights. I am actively looking for the wisdom that the frustrated person or subgroup carries for the whole group. In group relations theory, every individual holds something for the whole group. It could be an emotion, and/or experience. Discovering this pearl of wisdom means finding what the individual is holding for the whole group, which helps veer away from scapegoating the person/group who disagrees. I’m not talking about looking for a compromise. I’m talking about listening to the wisdom in the outrage. The wisdom in the outrageous. Digging deeper for a kernel that will change the whole group’s dynamic from conflict to shared purpose.

Fourth, ONLY once I’m clear of what the wisdom is, I start a separate group of conversations to identify solutions. In tending to the margins, it’s important to not look for solutions too soon. Sometimes I call the frustrated folks back. Sometimes I make a small adjustment in the process, to incorporate the critical opinions. Sometimes a radical change of direction is needed.

To people on the outside, tending to the margins looks like pure magic. “How did you do that? How did you get everyone on board?” I hear this time and time again. I’ve seen the person/people in the group that others labeled difficult, come around once they saw their concerns listened to and incorporated in the future direction of the group. The others are stunned that an agreement was reached at all.

***

Tending to the margins is hard right now. Trump and trumpers stand for everything my America, focused on inclusion, is not. Yet listening, deeply listening to the frustration of the America that voted for him is really important right now. Especially, but not only for white folk. We need to listen, not agree, but listen. Otto Scharmer called it understanding the blind spot that has created this condition.

I’m one of those white people who function in predominantly Black spaces. The white spaces I navigate tend to be progressive ones. I don’t interact much with conservatives these days.

I’m feeling a real strong need to understand, to find the wisdom, in what seems like retro insanity. Is it that poor, rural, white America feels despised and dismissed by a country dominated by the urban coastal cities? That a country that governs from the coasts and dismisses the majority of its landmass is unsustainable? Our electoral college supports our coastal privilege? Is it that in our strife for diversity and inclusion, we underestimate how hard the white poor has been hit? Is it that we spend too much time despising our own instead of organizing our own? Is it that we are using white supremacy divide and conquer tools ourselves every time we use the term “hick” or “white trash”? Have we failed to build class alliances? Too much time on our phones at Sunday dinner? That the white poor continues to support racism in bad faith? In good faith? Maybe all of this or much more. Many pundits are writing articles on all of this, as I too write. I’m not calling upon you to read more articles, though you may choose to. I’m calling on you to face those who don’t think like you with genuine curiousity. I’m launching into the next week with this intention. I hope some trumpers set a similar intention for their interactions with me. It’s important I step into this work, becuse given the rising hostility, it’s even harder for my brother and sisters of color right now.

There’s wisdom in this mess for our nation. My process with groups teaches me that. Even on the discouraged days I least believe in a shared purpose, I still know it’s possible. I must look for the wisdom in the outrage, the kernel that will change that can unite us in spite of what we are experiencing right now.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Facilitation

On a recent work trip to Ethiopia, I led and facilitated a group of 15 researchers collecting stories about adolescent girls for Girl Effect with SART, an Ethiopian Research company. We followed a BBC crew showing a documentary about stories of Ethiopian girls.

I used participatory leadership practices to build the team’s spirit and commitment to their work. For the team to take ownership of the process, they needed to understand the importance of women’s experiences. What better way for this to occur than on our own team? But in the meetings, the women were quiet.

A researcher collects a young storyteller’s story

1 / 4

StartStop

During the first two days of working together, I was frustrated. Everything I learned about facilitation was not working. One-on-one informal conversations flowed, but once the team was in a meeting, my opening question would be met with silence. “What are you learning about this community?” “What would you like to share about your experience today?” “Did anything stand out?” On the third day, the coordinator approached me and said: “Dr. Rita, the questions you ask, they’re too ….they’re too hard to answer. That’s why we’re quiet. We’re Ethiopian. We don’t like to break the ice. We prefer silence.”

I asked him to guide me in ways to overcome these challenges, and I learned to begin with more concrete questions (“Who facilitated groups today?” “Were young girls more responsive in smaller groups?” “Were girls looking for validation from facilitators?”). I also asked team members to respond to a question by going around in a circle, which made it easier for people to speak up, as their turn was designated and expected.

This worked well in debriefing the research process, but didn’t address team members’ emotional needs. Though the project was short, the two weeks of data collection were very intense ones for the researchers; the more they collected stories, the more stories of physical violence against children, rape, hunger, and tremendous poverty emerged. I could see the team becoming sad, worn out, and overwhelmed. I could sense the team spirit wavering.

I wanted to offer my support, yet, as a western researcher, it was unlikely that they would come to me. A strong sense of reserve and dignity kept team members from sharing their challenges. Still, I continued to hold space for the hard conversations in our meetings. At each meeting, I asked if there was discomfort, and I renewed my availability for anyone who needed me. “Are there any stories that were hard to hear?” “How do you feel collecting these stories?” All questions were met with silence, yet I was no longer worried. I could sense that spirits were not as heavy. Just by having the option to talk, members were lightening up.

Later, I asked the coordinator if team members ever talked about their experiences AFTER our meetings: “Yes, last night we did, and for quite a while.” “Good,” I said, “I don’t have to hear the conversation. I just want it to take place. As long as you go to each other about how this work makes you feel so you don’t burn out.”

I was happy hosting the silence that generated later conversations. I didn’t need to hear the whole conversation. Sometimes all a facilitator can do is host the silence that plants the seed for conversations to grow in better-suited contexts. English was not my researchers’ first language, and I was not a person from their culture. If the conversation didn’t take place in my presence it didn’t matter.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Facilitation

In 2012, I hosted a retreat for Kito International an organization in Nairobi, Kenya that trains street youth to establish their own businesses and move towards self-sufficiency. The founder Wiclif Otieno is an ex-street youth himself. In a country with a 75% unemployment rate for people ages 18-35, it is a painful truth that 300,000 youth live on the street.

Our purpose for the day was to envision the best possible future for the Kawangware community of Kito’s site and to identify ways to move in that direction.

The founder also wanted the organization to transition to peer-training by inviting two youth who completed the program to train other youth. We had a morning World Café with the guiding question: “What can we envision for Kawangware?”, a teach-in on the Chaordic Stepping Stones, an afternoonOpen Space with a guiding question: “What can we do together that we can’t do alone?”, and a Circle Council intended to facilitate making a decision about peer-training.

In a Circle Council, Circle Practice is used to make decisions by: 1) One member proposing a decision needing to be made; 2) Each member speaking their opinion and feelings about the decision; 3) Members speaking up on what is clear to them; 4) Creating a set of options; 5) Voting on the options; and 6) Building consensus by working with and modifying the most-supported option.

Circle Process in the Kito International home office and workshop site in Nairobi, Ken

1 / 3

StartStop

I chose to facilitate this decision-making structure because I was told there was disagreement among Kito’s stakeholders. I hoped that new, composite solutions would emerge via the overt expression of different opinions in the group.

After the founder presented the decision to participants, however, I watched as one after the other, each person agreed. I was surprised. I had chosen a structure intended to build consensus. What should I offer a group of people who already had that? What was being hidden under the surface of people’s approval? I had no choice but to listen and think at a deeper level. Otto Scharmer calls it Sensing: listening to the spoken and unspoken and seizing the opportunity for the new to emerge.

In this “sensing” space, the room felt somewhat cold and distant, and the consensus somewhat volatile and superficial. Maybe the youth didn’t want to challenge the founder out of fear of affecting their relationship, gratitude about being included, not feeling qualified to disagree, or maybe because I, a foreigner, was in the room. Sensing also revealed that the two potential peer trainers felt intimidated by the role they were being asked to step into. What could I offer to move these feelings about insecurity and fear of change into a more generative space?

I led another circle and asked: “What do you think the youth trainers need to fulfill their role to the fullest, and what can you offer to support them?” As each participant voiced what they thought the youth needed and how they could provide support, they also spoke of qualities already possessed by the youth: joy, determination, commitment, enthusiasm, willingness to learn, companionship, and respect. I watched the youth change from slumping in their chairs, to sitting tall, backs straight. Eyes went from droopy to lively. The atmosphere lightened, the smiles became abundant.

***

I’m pleased to say, that the youth trainers have now trained two groups and are confident in their abilities. “I learned so much by teaching.” One youth trainer told me this summer. “I learn from my students, every day.”

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Program Evaluation

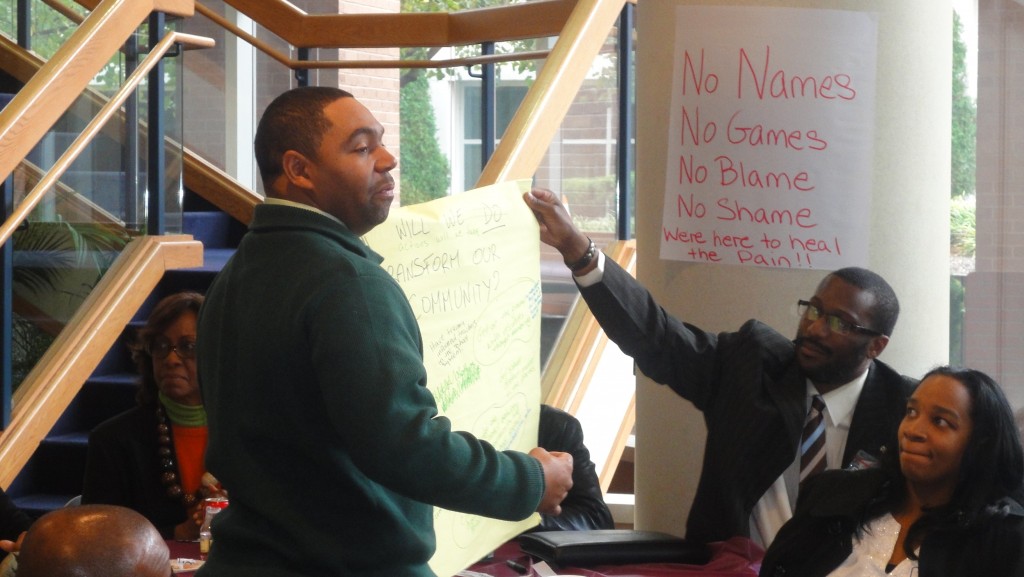

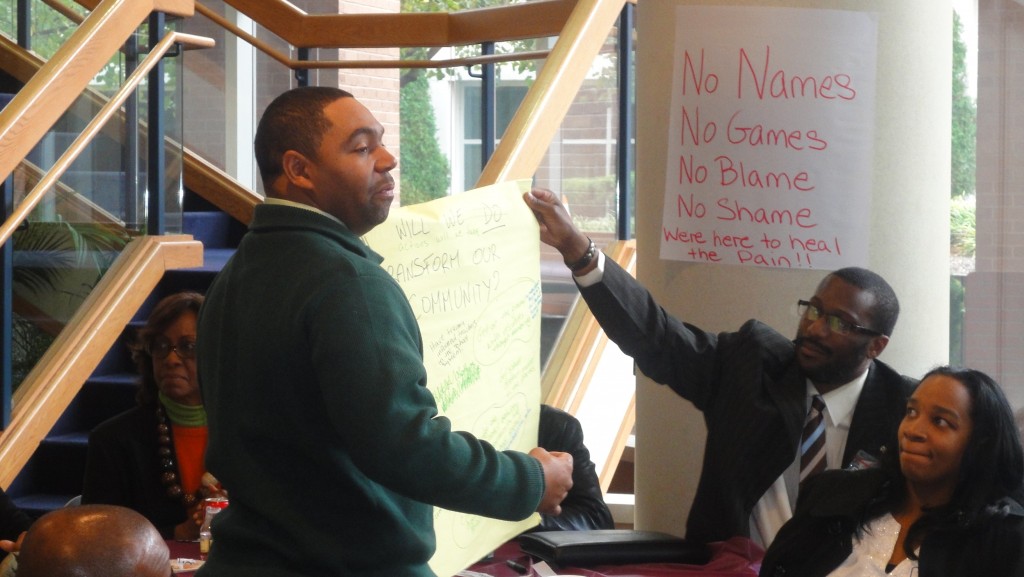

I recently was hired to help a group of people (Chester Real Change) generate a visual model that represented the transformative process they collectively experienced regarding the impact that violence had had on them.

As a participatory leadership facilitator, I worked with my client to create a structure for a retreat and questions that could meaningfully generate deep reflection. We decided we would start with personal process and then move to group work and image generation. I proposed a 20-minute individual journaling session that would encourage reflection on the following questions: What changed for you from the beginning to the end of the process? In which moment did you experience the shift? What helped the shift unfold?

In 5 minutes, participants were done and laughing and talking. Struggling to control any expressions of irritation, I asked participants to share their reflections.

“Well, I don’t like the term ‘shift’,” One participant said. “Things didn’t really shift for me. Things didn’t change; it’s just that I was having a group experience. For the first time, I got to meet other people who had to deal with violence in a different way.”

Community building in Chester, Pennsylvania

1 / 3

StartStop

“So,” I asked, “if you were to pinpoint the moment in which you felt that community, the moment in which things changed for you, when was it?”

The director of the host organization stepped in: “What I’ve learned in this process is to NOT do what you are doing, which is to contrast, simplify, and interpret other people’s answers, but to listen to different perspectives. I think she gave you the description of her experience, and you need to listen deeper and not try to change what she said.”

The handslap hurt, but was helpful and needed. I realized I had forgotten to take off my evaluator hat: I had focused on desired outcomes and pushed the conversation instead of allowing it to go where participants saw fit. Otto Scharmer in Theory U would say that I was thinking from limited past experiences instead of presencing: stepping into the possibilities of the future by sensing and connecting with it as it takes form.

Scharmer says that you sense and connect by holding an open heart and open mind. I wasn’t open enough. Generating a process for facilitation is very different than generating one for evaluation. With evaluation, you stick to a process to identify and measure desired outcomes; in facilitation, you must let go of the process and allow it to change, trusting that a vision of the future will emerge.

I was grateful for the director’s comment (and thanked him), because it allowed me to take off my evaluator hat and allow the future to take place instead of pushing and planning for it to do so. The moment in which I became aware of this I was able to hold the space for more generative listening, and I engaged participants in the active role of letting me know if the process was working for them. I checked in with participants and made many variations to our process throughout the day.

As the best meditation practices teach us, once you let go of the strong attempts to empty your mind, you may achieve that which you desire. Similarly, when I completely let go of my facilitation goal, not surprisingly, a conversation took place where we identified the image we so aspired to create.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation

On a recent evaluation and facilitation project, I came on as the new hire to a well-developed team. The client was a prestigious foundation, and it was a high stakes project for everyone involved.

I was expected to hit the ground running and had no time to get myself acquainted with the particular work style of this team. Over time, my initial discomfort increased, rather than decreased. My colleague’s management style favored attention to details over big picture thinking, and I learned from this process that I’m more of a big picture person.

My gut started to tell me we were missing something. I didn’t feel comfortable asking my busy colleagues to talk about something I couldn’t put my own finger on, though. Imagine asking a colleague: “I want to have a meeting with you, but I don’t know what it’s about!”

Instead, I retreated into a deep, self-critical mode. “My discomfort must be about my ego,” I thought. Did my ego create the struggle with my team because the management style being utilized was out of my comfort zone? Was my ego trying to push the big picture on the table at every meeting to gain control? Did I simply need to trust my colleagues more and let go?

So I tried something different. I gave my ego a good slap, and practiced letting go for the next few weeks.

Over time, the fact that a big-picture perspective was missing gave the project an unexpected jolt. After we identified a strategy to address the jolt, I found myself feeling more relaxed, and the nagging feeling was gone.

It was then that I realized that my discomfort had not been ego-driven. It was my intuition prompting me to pay attention and speak up.

Over the course of the project, I had chosen to silence my intuition, when instead I could have hosted an explorative conversation. I could have said: “You know, something in my gut tells me we’re missing something, but I can’t put my finger on it. Could we have some time, maybe just 30 minutes, to brainstorm on our overall framework to see whether my feeling is well founded?” I’m sure my teammates would have accepted the invitation.

While maintaining a practice of being aware of one’s ego getting in the way is a helpful one, I now aspire to host a balance within myself between self-critique and self-trust.

Maintaining this balance is critical self-facilitation work because both extremes –self-critique and self-trust– can strangle conversations. Both can make us get so wrapped up in our own minds that we lose touch with the needs of a group or process. We disconnect from the intelligence of our hearts, which can guide us through challenges. Hosting that balance within ourselves allows us to host it in the rooms where we carry our craft.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Participatory Leadership

My colleague, Alissa Schwartz dreamed in her sleep about a new facilitation structure where a group narrates its history. In a circle, ordered from youngest to oldest, each person shares everything they know about the group’s history. The mystery unfolds as the elders speak towards the end. In this blog I share an experience in which I applied this process.

***

Within three weeks of Alissa sharing with me her dream, I had the opportunity to apply her structure twice! I was evaluating a consortium that supports African civil society organizations with Encompass a fellow facilitation, evaluation, and training company. The history of the consortium was very complex. Even by reviewing existing documentation, we had challenges understanding how approaches shifted over time.

At two meetings with multiple stakeholders, I facilitated History Circles. I made three modifications to Alissa’s design:

- I asked participants to order themselves from youngest to oldest in terms of their organizational membership and/or knowledge (instead of actual age);

- I allowed people who had already spoken to build upon someone else’s information, if they had forgotten to say something during their turn; and

- I sat at the center of the circle and graphic recorded their history on a timeline.

During the first meeting in Boston, the structure worked beautifully. The first people who spoke had the most simplistic views of the consortium’s history and described the moment they received their American funding as the beginning of the process. The last three people to speak carried the most knowledge and offered many stories about how the process began in Africa, among organizers, before any funding was received. The younger members listened with interest, and participants extended the storytelling during lunch, listening to an elder describe the consortium’s earlier years. It was a modern adaption of a traditional circle of elders. The total process lasted a little less than two hours.

I repeated the process in a meeting in Togo in West Africa. This time, it took only an hour, as most members were new to the consortium and had little to recount. For most participants, however, the pace of the structure was too slow, maybe because they were younger and more lively than members of the first group. Yet, participants appreciated the process of learning about their organizational history.

One African participant said: “This exercise is very helpful. We focus on the job and what people expect of us, and we don’t spend time on the history. This inspires us that when a tree grows, it gives flowers.”

The storytelling circle process has many strengths:

- It allows an outsider to hear most of the organizational or community history at one sitting;

- It allows the group to create a collective narrative of its own history;

- It supports a group reflection of a shared growth process; and

- It fosters awareness in the group of historical misinformation, as the newer members speak first, often sharing misperceptions that later get corrected when the “elders” speak.

I found three challenges to emerge during the process:

- Pace. Depending on the number of people involved, it can take a lot of time. It is also hard to time-manage individual contributions;

- Debrief. Once the last person is done talking, many participants are ready to take a break and do not want to continue in conversation; and

- Documentation. Corrections are made throughout the process, and as a graphic recorder or note-taker, you never know what will emerge from each person’s account.

Here’s what I did to overcome these challenges:

- Pace. The process works best with 10-12 people, at most. Remind participants not to repeat what has already been said;

- Debrief. After a break, I facilitated a quick-paced world café with 10 minutes per round; and

- Documentation. Before I began, I drew a timeline. As I recorded, I color-coded reoccurring information, such as meetings, problems, agreements, and practice.

We welcome other ideas about how to use and adapt a Storytelling History methodology. Try it out for yourself!

Recent Comments