by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Inclusive Conversations

Many friends have talked to me about struggling with Facebook posts on their “friends’ ” timeline especially in this time of heated presidential debates and recent tragic terrorist attacks in Nigeria, Lebanon, Mali, Turkey, Ivory Coast, Belgium, and Pakistan. Some posts were prejudicial, others blatantly racist. The way Facebook is structured, someone’s status shows up on our feed, so many of us feel the need to “call out” misinformation and prejudice, and feel deeply disturbed when we choose silence. It is known that reacting to Facebook posts can create more trouble in relationships and friendships.

I believe in calling out prejudicial behavior during personal interactions. I value calling out injustice, because being silent also means being complicit. Speaking out is also an opportunity to begin an inclusive conversation: one where differences are seen as an opportunity instead of a threat.

But Facebook is another beast. I do a lot of thinking about this context before I step into the ring. Yet this concept of always calling out injustice, I believe predates Facebook. Since Facebook is not a face-to-face interaction, I found it rarely promotes genuine dialogue when people have divergent opinions. So in front of my Facebook feeds, I’m presented with choices of how to react: calling out or being silent. This is a false duality and we have other options:

- Assess the context: Am I trying to win an argument or am I coming from a place of curiosity? Who is this person and what is their relationship to me? How is my comment likely to be received? What are the advantages/disadvantages to commenting on someone’s wall? Would sending a private message be more effective? Am I/they likely to be/feel attacked; if so, have I done this before? How do I feel today? Am I in a space to be able to engage mindfully? I am capable of being completely present to the person I’m communicating with or am I frustrated about something else in my life and taking it out on them? Am I in a place where I can engage and freely let go if the conversation doesn’t go as I would like?

- 2. Call out: I can name the assumptions in a person’s discourse, their misinformation, the impact of their perspective on the world, the injustice, or the discriminatory effect on a targeted group. I could also just state: I disagree, and point out other points of view.

- Be silent: this option can range from withdrawing after I say my opinion to not saying anything at all. Is this the right venue for what I have to say? A friend of mine recently wrote under her FB post something I admired: “P.S. I have no interest in being part of any intense Facebook arguments. Happy to debate in person, but internet discourse can become hostile too quickly for my taste–perhaps because we cannot see each other’s faces. Just sharing my thoughts.”

- Ask questions: can I identify a question that will help me point at the default in the thinking? Can I ask a question that promotes real communication and inquiry?

- Post and article on my own feed. I can choose to be more explicit in my own personal stance by posting articles with my perspective. The other person might notice, just like I did, and maybe read it.

- Offer a reflection: I can invite the other person to reflect. This may be best done by me getting off my pedestal and offering an example of a time when I too, thought the same way or made the same mistake they are making.

- Use the misinformation in a different context. Sometimes the most awful things I see online, I can repurpose in a different conversation, article, lecture and/or training. When I use my moments of outrage as teaching moments for me, I can reflect deeper into why I think the way I do and gain a sense of empowerment by using the information in a different way.

- Deconstruct the thinking. Gain insight on another perspective, analyze it, debunk the underlying assumptions, and key inquiry questions so that when I’m in an actual in-person interaction I’ve done some pre-thinking about it. I make this choice often when the online situation feels like it would not promote real dialogue.

- Create other opportunities for dialogue that enable me to engage with people who have those opinions. If I’m dissatisfied with the need for real conversations around the issue, I can become more active in creating opportunities to engage in conversation in diverse groups. I can start anywhere, friends, religious community, neighborhood association, parent association, or activists. Chances are, my Facebook friend is not the only one with those opinions.

- Increase my capacity to continue dialogue in the cases of extreme differences of opinions. I can use my outrage as an opportunity to build my own capacity for real dialogue. I can attend some trainings, for instance that can help me build my capacity for having hard conversations. The following have been best for me:

- The Virtues ProjectTM helped me pay attention to someone else’s strengths while in the conflict, it gave me language to express appreciation, too.

- Art of Hosting taught me to stop controlling conversations, breathe freedom into them, and helped me find the courage to name what was really going on;

- Group Relations taught me what in my personal history was getting me locked into similar conflicts over and over again.

- 11. Establish relationships where I can be held accountable. No matter how progressive we think we are, there is always space to grow. This can be done by identifying a group of like-minded people with whom to build accountability to check my own ability to have open dialogue. Establishing ally relationships to have people I trust who can point out to me my underlying assumptions. These relationships can be a godsend especially when conversations go awry despite how hard I try.

I must admit that assessing the context (no. 1 above) with honesty and integrity towards myself and my motives, is always the best first step. When, instead, I dive right in with a solution, I’m often in a more vulnerable position of being hurt. And some days, like all of us, I still forget.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Inclusive Conversations, Participatory Leadership

In the last blog, I listed a self-care tip for having inclusive conversations: choosing when and where to invest your energy. Inclusive conversations are conversations where differences are seen as a resource instead of a threat. These conversations can be tricky because differences can bring up fear, hurt, or anger.

Today’s tip is also about self-care. If you’re not taking care of yourself in a conversation, or hosting yourself, and being present, as the Art of hosting’s four-fold practice would put it, then it’s unlikely that the conversation will be productive. Inclusive conversations are often hard and courageous conversations. So today’s tip: Look for allies and build support before you jump in.

I used to think I had to always speak out against any injustice, prejudice, and imperfection to be a worthy activist. Once, I was a member of a mixed activist group. The leadership was all white while most of the activists were African American. I demanded the leadership confront its own privilege and stop gatekeeping opportunities for a more diverse leadership. In a public meeting, designed just for this purpose, the leadership attacked me and attempted to taint my character. No one stood up for me. When I looked around the room, I was alone. I had no allies.

Two painful months later, one of the activists contacted me. “At the time,” she said, “I didn’t know what you meant by “gatekeeping,” but now I understand. Sorry I wasn’t ready to support you and stand up to the leadership.” See, she didn’t know because I had not built my support network. I learned from the experience that slamming my head against the wall of authority and power is not activism, it’s masochism. One is more likely to burn-out this way. It took me years to recover from the experience. I was scapegoated other times in a variety of groups, until I understood how scapegoating works and what I was doing to help it.

Scapegoating is a common group dynamic. When uncomfortable feelings arise in a group, there is a tendency to project those feelings against the person who inspired them. Truth-tellers are easy scapegoats because they say things that others try to hide. People who are very empathic are most susceptible to being scapegoated, because they can unintentionally take on the emotions of the group. By blaming the scapegoat, the group can avoid facing its own feelings of fear, discomfort, and hurt. Those feelings are projected to the scapegoat.

Scapegoating is not a right-wing thing, though we are hearing a lot of it in this presidential race. I’ve been scapegoated among conservative circles, liberal artists, radical hipster anti-racism activists, and preppy extra-educated psychologists. Scapegoating is everywhere. Just start noticing in any community how the gossip is concentrated against 1-2 people. Ladies and gentlemen, those are the scapegoats.

If you’re interested in knowing more about scapegoating and group dynamics, let me know and I’ll be happy to write more. Those of us who become scapegoats, experienced it first in our own families. A group relations conference helped me see this and set this painful experience to rest once and for all. But that’s a much longer story. For now, I just want to mention one easy tip.

Since I now know my tendency to be scapegoated, as soon as I enter a new group, I take some time to build relationships and get to know the people around me. I’m intentionally looking for allies. I’m intentionally building a support system for myself and others. I’m also learning what is perceived as “normal” in this group. I try to not step into conversations about power and privilege before I have a clear understanding of who this group is, how many people share my views, and who speaks truth to power and can offer me support.

Not pushing the envelope too soon has another effect, it helps me host the group, the fourth step in the four-fold practice, in Art of hosting terms. In other words, it helps me learn the group culture, see where the group is, get a sense of where it is going, and choose the most strategic time to make a controversial comment.

You think this is an easy cop-out? Think twice. Allies and timing are strategic. If a group is ready to be challenged and go deeper, it will be less willing to scapegoat you and your contribution can be more transformative. If you choose to oppose the larger group, doing it with allies by your side can be more effective because a group of people acting in unity are harder to scapegoat.

The newly arrived, isolated person who is quick to question what is normal for the group is the easiest scapegoat ever. These days, before I choose to do this, it better be worth it.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Inclusive Conversations, Uncategorized

Do your conversations these days feel like black holes of despair that transform even the sweetest of donuts into booger-tasting jelly beans? If most conversations you have about these crazy primaries end up in fights and go nowhere, tip #4 is for you. Inclusive conversations occur when differences are seen as a resource, not a threat. Previous tips included preparing the conversation, choosing when and where to invest your energy, opening the door to the conversation and making allies. Today’s tip is more about the actual conversation. Tip #4: No matter how insane you think people are to think the way they do, don’t beat them down with what you know, try to pause, and meet them where they are, instead. But before I explain what I mean by: “meet people where they are,” here’s a little story for you.

Sunday dinner, with my family in Italy and we’re discussing child prostitution. I was probably 20 years old. Yes, in my family this is what we talked about over Sunday dinner, along with everything else controversial, like war, politics, and inevitably, the corruption of the Catholic Church. The final cherry on the cake? The ethics and moral stature of our local priest. And this is where I got my Italian equivalent to what in the United States would be “debate team” training.

Here were our rules:

1) To get the stage, you had to yell louder and gesticulate bigger than everyone else.

2) Once you had the stage, you had 5-10 seconds to make your opening statement.

3) If your opening statement was persuasive, you could keep the stage for another minute, but only if you didn’t get distracted by the five people who were revving up their motors to jump in.

4) If your opening statement was weak, you would lose the stage.

5) If you paused, you’d lose the stage.

6) If you stuttered, you’d lose the stage.

7) If you had the stage for a whole minute, or two (which meant you were a pro) you had to have a final punchline to end your point to win.

8) If you lost, someone would interrupt you.

9) If you won, someone would interrupt you.

Brutal rules, I know. It was our bonding time. Bonding through fire. Our Sunday dinners were notorious for being loud. Even with the doors closed, neighbors on the street could hear us arguing. And Grandmom’s (Nonna’s) house is an earthquake-proof cement house in the open country-side and the street was a quarter a mile away. The men joked that they needed a traffic light to get a word in edgewise. We are a determined bunch of folks. We could run you down with words, any day, anytime of the week, just to be right. With this kind of training, I’m sure you’re not surprised that conflict in my family is an everyday affair.

Hot peppers (that my grandmother planted) in front of her house in the countryside. The road borders the property. The houses in the distance are on that road.

But back to the child prostitution dinner. “You have to persecute the men, because the men are the clients, and without them there would be no…” my aunt yells. “Go after the traffickers, you know the mafia is allied with those crappy politicia…” my other aunt interrupts. “It’s all the priest’s fault”, my uncle says, just to instigate the crowd. This is 15 years before the catholic sexual abuse scandals. The men in my family blame priests for everything. It is their weekly excuse for sleeping in on a Sunday morning instead of accompanying their wives to church.

An uncle who has been quiet so far and really hates the exponential volume of these conversations, finally screams: “What the hell do we care? Really? This doesn’t affect us!” Perhaps this was an ill attempt to quiet things down but I was livid.

“It’s that type of not-giving-a-damn-attitude that puts girls at constant risk…” I yelled. I listed every study on violence against women I could think of. I kept the stage for a whole two minutes. My heart was pounding as I was yelling at the top of my lungs. And then my last fatal blow:

“Let’s see if you care if it happens to your own daughter.” He was immediately offended and shut down. He got up and may have gone to the bathroom. Everyone else got up to clear the table. We dispersed. We moved on to talk about the mafia and the politicians’ role in everything that is wrong with our country. I’m thankful for my brother who said to me that day: “You’re right and you make good points, but your tone is so condescending no one will ever listen to you.”

The view of my grandparents’ land and tobacco fields.

A few years later, someone told me something very similar. We were having dinner at my place in Rome, with some of my African friends. We had a fiery conversation about the United States’ international imperialism. A dear friend said to me: “You know more than most people do about this stuff, but the way you talk, you push away people who could be allies, instead of helping them get curious to find out more.” That’s when it finally hit me. No one listens to what we say when how we say it makes them feel inferior.

After six years of college in Italy and six years of grad school in the United States studying the history of racism, discrimination, and exclusion all around the world, I had more material that most to offer a great, easy to win debate. Academia taught me to not win a debate by interrupting, but with logic: name the assumption your opposition is working from, display ample historical evidence that proves those assumptions to be wrong historically, move to how the historical evidence lives on today. Propose a solution. Final punch. It was a different tactic, but it created the same effect. There is a winner and a loser.

We are taught to debate this way in the academic world, it helps us establish credibility, prove we are qualified and gain self-confidence in what we know. But the systematic beating people down with evidence is not effective at helping people see another point of view or at making allies. Both parties in the conversation eventually walk away empty. The “loser” walks away feeling horrible about themselves. They also walk away feeling horrible about the world we live in. This person’s curiosity is not stimulated. The apparent winner may feel an ego boost at first, but eventually feels disconnected and alone, depleted by the conversation too.

Great teachers know that they cannot teach a student unless they know first, what the student already knows. New knowledge depends on pre-existing knowledge. Communication specialists will tell you that that unless you know what your audience cares about, you cannot communicate effectively with them.

So for today’s tip, instead of beating people down with the knowledge you have, try meeting people where they are. This expression is common so here are four ways I’ve learned to do this that I recommend:

- Find out what the person’s current knowledge is on the topic.

- Find out what the person cares about in other aspects of their life.

- Give up any false sense of superiority and talk to them as peers.

- Prioritize the message with very few points and relatable examples.

- Relate your key points to the topics the other person cares about.

- Ask questions, before, during, and after. The conversation is not over once you make your point. There is no touchdown scoreboard.

- No matter how much you think you already know, make sure you learn something from the other person too.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Inclusive Conversations

When you take a stand, it doesn’t have to be you against the world. Taking a stand can also inspire a group to be the best it can be.

Until now, all the tips on inclusive conversations were about being receptive, asking questions, and listening. Today’s tip switches gears: it’s about taking a clear stand in the presence of flawed process.

Some years ago, I was a member of a committee in a strategic planning process for a larger organization. As is typical in strategic planning, the committee brainstormed goals, prioritized them, and then asked the organization’s membership to vote on them. One of the goals—which I had proposed—was to increase the diversity of our membership, which was predominantly white. Once the wider membership voted on the goals, the diversity goal received fewer votes. Only 60% of the membership voted for more diversity versus the 70% or higher approval of the highest-ranking goals. I realized that the process itself was flawed. The people who most cared about diversity were not present in the organization, therefore could not vote.

In our recent presidential primaries, candidate Bernie Sanders has taken a stand calling out the flawed process.According to a recent Reuters/Ipsos poll, fifty-percent of Americans agree with him and two-thirds want to see the process changed.

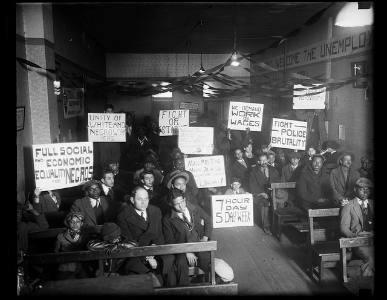

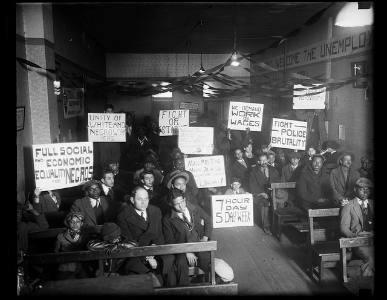

Unemployment rally at local Communist Party on March 5, 1930 to advocate for better labor conditions

As a member of the committee, I chose to take a stand.

“Given our predominantly white membership,” I said to the committee, “I argue that 60% is a high percentage, even if it is not the highest. If we had waited for any social equality goal to be voted upon by a white majority, our country would still be under legal segregation. Majority rule is not an appropriate process for choosing to increase diversity, because, many who might benefit are excluded from our membership and do not have the chance to vote.”

“But what benefits does diversity offer our whole membership?” someone asked. This is such a common question. The hidden privilege behind this question used to infuriate me because it assumes that the majority has to benefit from any action before it gets approved. It basically means “what do I get out of this?” The question no longer infuriates me. I prepare myself for the answer, before it’s even asked.

“There’s an abundance of research about how diversity improves the way people think, helping them think more deeply and creatively. We have much to benefit. I also suggest we keep diversity as a goal to choose, as an organization, the higher moral ground. Let us choose to be intentionally inclusive instead of passively exclusive.”

It worked. The goal was included in the strategic plan.

We Can Do It!’ World War 2 poster boosting morale of American women contributing to the war effort created by J. Howard Miller in 1942.

Then we recognized, like many organizations, that we didn’t really know what we were doing to be exclusive. The first objective became to find out why and build partnerships with other, more diverse organizations to grow a more inclusive membership. And it’s working. There is now a committee of people working specifically on the goal. I’ve drifted away from the work, taken by other priorities, but the work is continuing.

But before taking a stand, consider the following reflections:

- Check your motives. Are you doing this just to be “right”? What do you want to achieve and for whom?

- Check your morale and mental state. Taking a stand can have a negative effect on you. Are you in the best emotional and mental space to take this on?

- Check your allies. Are there people in the group you can reach out to support you? Check Tip 3 on the risks of not doing this.

- Check the assumptions. Are there assumptions that need to be named to make a more persuasive stance?

- Check the benefits to your audience. What does your audience get out of supporting your stance? Get clear about this before you speak up.

- Check your patience. Sometimes pushing too hard can have the opposite effect. Make sure to include patience and pauses in your plan. Oftentimes, a pause can build support because people have a chance to reflect.

- Check your learning. Try to not shut down when you take a stand. As for any other conversation, keep asking questions and learning from the perspectives of others in the group. The more you listen to others, the more likely you are to be listened to.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Inclusive Conversations

Got relatives or friends on the other side of your political beliefs? Can’t get three words in before the conversation gets rough? Do you avoid talking all together to avoid feeling awful? For my series on inclusive conversations−conversations where differences are seen not as a resource, not a threat−and this tip is for you: don’t word-pick, empathize.

Here’s how this tip became real to me.

Italy. Summer of 2008. It was the first summer Obama was in office. I was in a pub in Rome having a drink with two good friends and some of their friends I barely knew. It was Obama’s first year, and Europe was thrilled and relieved that we just abandoned the Dark Age, religious crusade era of George W. Bush. Hope was in the air, for a man who could compose a grammatically correct sentence, inspire the audience, was savvy in international politics, and had used hope, rather than fear, to galvanize his voters.

One of my friends introduced me to the others as an expert in African American culture, given my PhD in African American Studies.

Someone asked, “So what do you think about Obama being elected? Has the United States stopped being racist?”

“Well,” a second person replied, “you can’t ask that question, because Obama isn’t really Black.”

In the context of the United States, that was of course an offensive statement.

People had accused him of not being Black enough during the primaries, but this was Italy, a different context all together. They knew little or nothing of that aspect of the American controversy.

Italy has not had a movement for political correctness and people are extremely blunt.

I was tempted to word-pick. I have been trained to. I was taught to word-pick debating in college: “How are you defining ___?” And the conversation shifts to definitions, away from the original topic. It’s a good stalling tactic, but it’s not a good bridge builder, like most debate tactics. Debating is about winning, not about building understanding. And the word-pick debate is often useless, words are used differently in different cultures, contexts, by different people, even.

I tried to not beat him down with knowledge (see Tip #4 Meet people where they are). Instead:

1) “Don’t get furious, get curious” it’s a tip from the Virtues ProjectTM. When someone says something that comes across as offensive, try asking questions.

“Why would you say that?” I said.

“Because his mother was white.”

“Actually in the United States, for centuries, a one-drop rule defined Black any person with any African ancestry. So most people with any African ancestry in America consider themselves Black, because they are treated as such. Plus, Blackness in America is cultural, not just genetic.

“Oh. I thought that because he’s light skinned, there would be no prejudice against him. You know like Berlusconi saying, “he’s just a little tanned….”

2) Ask more questions. Try to understand why they think that way.

“What makes you think there’s no prejudice?”

“He’s a lawyer, he looks cool, he’s not that dark, like here, you know Black people here are really Black (Italy has a large Senegalese immigrant population)……when we see someone like him, we don’t think of them as Black.

“Do you see why what you just said is offensive?”

“No, I don’t. I think the Italian leftist media is exaggerating.”

The attack on the media. The ongoing defense of the populist millionaire mogul who had “such a high opinion of himself that he thinks it’s acceptable to say anything to anyone.” Sound familiar?

Don’t get confused, I’m talking about Italy, 2008. Americans made fun of us back then for the galvanizing appeal the billionaire media mogul’s simplified messages had. Because he was rich, “Many Italians were convinced that he would do for their country what he did for himself.” But he didn’t.

He left the country in shambles, looking only after himself. He governed for 9 years and was a prominent political leader for 19 years, 1994-to 2013. What finally got him out of politics (but only for 6 years, let’s see what happens in 2019) was a tax evasion lawsuit. The many others (2,500 trial dates across 17 years as prime minister), distortion, corruption, prostitution of minors, could not. He had passed a law while in power that people in congress could not be persecuted and another law that people over seventy could not be locked up. So he’s “paying” now with community service, while Italy stumbles to recover from 20 years of populism and a destroyed economy.

We have a lot to learn from Italy.

Back to the man in the pub.

“Where do you read your news from?” I asked

He mentioned a right-wing Italian local newspaper.

I struggle to empathize – to see where he is coming from. He does not know the USA context, he does read USA newspapers, he doesn’t know any Black American people.

I taught him a few things about American history, the one-drop rule, ongoing discrimination, Black culture. By the end, I was offering him websites to read.

“You’re in the context, you know so many things, I don’t.” He concluded. “I’d be curious to read different kind of news about America. Over here we always get the same crap…”

This conversation ended well. They don’t always. I’ll have to tell you about one gone bad sometime….

And while giving up on word-picking may not change your opponent’s position, deep listening, just may. A new study says just that…there is hope after all!

Recent Comments