by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

Southern Italy is not the first place in the world where most people would turn their attention to when they think about oppression. My passion for understanding privilege and oppression in the United States and my choice to learn from African American present and past history is often puzzling to those who cannot see the link.

Ancient Norman Castle of Apice, Benevento.

1 / 6

StartStop

Well, over many centuries Southern Italy was invaded over and over again by Moors, Romans, Vandals, Normans, Slavs, Visigoths, the French, and Spaniards. This makes us a surviving people, and that’s why Italy has so many castles, arches, and other edifices – parting gifts from past invaders.

It took the Romans 53 years to get my people, the Samnites, to submit to their will. The Italian national unification movement, which created the nation of Italy in 1861, deposed our beloved and trusted southern Italian leader Garibaldi, as the northern industrial forces feared that the southern Italian agricultural workers would demand a social revolution and redistribution of land. This redistribution of land has been sought after since the Roman Empire, and is still relevant to the North-South conflict today.

Sound familiar?

There are three common internalized responses to oppression I hear a lot both in my small Southern Italian hometown of Benevento and in the predominantly Black neighborhood I live in, in the USA:

- “They won’t let us do anything.”

- “They’re jealous; as soon as you try to rise they will bring you down.”

- “You can’t do that.” (“It” can be anything from creating a workshop to a radical shift in political representation.)

These three common responses, I believe, are a strong indicator of a people who have never felt represented by their government and who have gotten accustomed to being repressed instead of encouraged.

This defeatist thinking is a hindrance to our work of building collective action. Overcoming it isn’t easy.

Carter G. Woodson, a phenomenal African American historian and thinker said it most effectively:

“When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his ‘proper place’ and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.”

I’ve done a great deal of inner-awareness work in the past years to overcome my self-sabotage and negative thinking mechanisms. I have made some progress, though I’m certainly not done. Being in Italy during the holiday season with my family while I offered seminars and workshops reminded me on a daily basis how the ongoing imposition of limiting beliefs is a way to keep oppressed people “in their place” and off the radar of innovation and world change.

It reminds me of how far I’ve come, and how much farther I need to go for positive thinking to become a default for me.

Breaking away and living in other countries may have allowed me to escape the hypnotic negative thinking of my people. I’m beginning to think that specific vibrations of internalized oppression are peculiar to a land and people, and it may be easier to live and operate within the context of oppression of a people other than one’s own. When I am in the USA, the pain I feel isn’t as paralyzing, internalized, and self-inflicted as when I’m in Benevento.

This reflection is helping me mitigate the judgment I feel about my own people that underlies my irritation with them. Reflecting on my peculiar positionality within my culture is helping me be a more compassionate daughter, role model for my cousins, and consultant in the work I am doing in Italy.

When I am in Italy and as I work with oppressed peoples around the world, I practice:

- Patience, as I recognize that it is my privilege of being able to travel that has affected the way I look at my own oppressed reality when I’m up close;

- Gratitude, as I appreciate the opportunities I’ve had to break away and live differently; and

- Compassion towards those who are still stuck in a negative-thinking cycle.

- Another view from my grandparents’ farm in Apice, the trees on the right and bordering the river.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

Just before this groundbreaking week, I attended a four-day Theatre of the Oppressed training for facilitators. This was my unintentional preparation for a week in which the South Carolina shooting and less-heard burning of Black churches, the Supreme court upholding of the Affordable Care Act and Gay Marriage. Whatever side you are on, the mix of these events are making our opinions about difference in America slap us in the face.

Photo by em_diesus

We can choose to do the deep work that allyship, forgiveness, and restorative justiceentail. This work is never comfortable. When we face the beast, we often want to run away. Most often this is because we discover that beast who we hate outside of us, is also within us, we have internalized it. We are not immune of the context we grew up in. I’ve learned that I no longer do this work to help others. I do it to embrace my own humanity in how I show up for others, but also how I show up for myself.

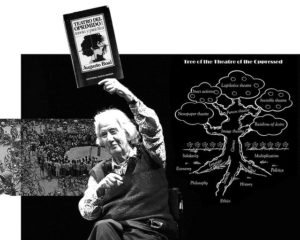

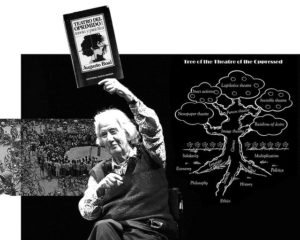

There are many different approaches to doing this “work.” One is the Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a groundbreaking way of using theatre and improvisation in groups to help people engage individually and collectively with how they have been affected by power structures and beliefs. Created by Augusto Boal, it is grounded in Paul Friere’s powerful Pedagogy of the Oppressed. By being spect-actors, simultaneously spectators and actors, participants have a chance to both reflect on a situation and offer strategies to overcome the challenges each solution presents.

I tend to take on a role in groups, one in which I challenge the group to go deeper. At times I’ve been painfully scapegoated for it. But the group in my Theatre of the Oppressed training was a singular group of people who are brave themselves and who are as passionate about facilitating conversations about power, inequity, and justice, as I am. So they welcomed my challenge and bid me higher, pushing me way out of my comfort zone.

In some small-group work, we set up a skit of a summer backyard party in which the owner, a white woman, Sally, who recently moved into the imaginary neighborhood, tells off the Black guy, Jamal, who’s lived in the neighborhood for generations, because he plays loud rap music from his car in front of her house. A friend and ally, Kate, steps in to support the Black guy and calm Sally down, but Sally is drinking. She gets louder and louder, nastier and nastier. As her sense of entitlement grows, so does her escalating rage. Here are some things she says:

“Not in my neighborhood.”

“I didn’t spend all this money to live in this neighborhood to hear that music.”

“This is why we don’t like people like you moving in.”

“What’s wrong with you people?”

“Shut that music in front of my house. This is my property.”

When Kate steps in to ask Sally to not treat her friend Jamal this way, Sally hesitates for a second, but then keeps going, even louder.

“Stop talking to me, I want the music off, NOW.”

Augusto Boal photo by LCR SAP

Kate is turned-off by the ineffectiveness of her attempt to support Jamal, she physically takes two steps back, even if she still wants to help. She doesn’t know how, the violence puts her off. Jamal is left to confront Sally. He is peaceful and brave. He offers a handshake: “I’m a neighbor, nice to meet you, can we talk about this?”

Sally barely concedes her fingertips, showing her disgust for touching him.

This was a theatre moment. But it truthfully depicts how quickly things can precipitate in our own U.S.A.

I was the one who played Sally’s role.

The instructor suggested: “Boal says there is a bit of the oppressor in all of us. I challenge you to discover what playing the oppressor will teach you.”

It has taken me two weeks to write about this powerful experience that Boal would call “the oppressor within.” The experience was as enlightening as it was horrifying. Here’s why.

- It wasn’t hard. I wanted to think of myself as such a “good person” that it would be awfully hard for me to stay in character. It wasn’t. I had a repertoire of experiences to play the role: a combination of conversations had, listened to, ways I’ve been treated, and emotional truth.

- Dismissing human beings. In Sally’s role, it wasn’t hard for me to dismiss these two human beings and anything they said to get what I wanted. What I wanted in that moment was more important than anything else. As if Jamal wasn’t a human being, he was just an obstacle to be removed.

- The ball of anger. Yelling at Jamal was like taking everything that had ever hurt me, from being made fun of in nursery school to being fired on the job, any resentment for anything I believed should not have happened to me, and channeling through, no against him. This was a spiral. Once it started, it was addictive. It was easier than I thought to let it escalate.

- The shame. After I stepped out of role, I had a deep sense of shame. I felt others more distant. Were others judging me for playing the role like I had? Were they asking themselves if this is really who I am? Is it?

- The isolation. Also after I stepped out of role, I felt so isolated, that I was questioning the foundation of my own humanity. I felt alone in the world, disconnected. I felt a sense of despair that only human contact could nurture away. John A Powell in a recent interview said “The issue of race is an issue of belonging.” In that isolation, I was terrified of not belonging anywhere. Thankfully, I know how to reach out for connection. I’ve learned to ask for help. How do the people who embody this harsh role to an extreme feel on a day-to-day basis? It brought to a tremendous sense of pity.

The oppressor in me is completely disconnected from others and my true self. The oppressor in me is judgmental, harsh, ruthless, entitled, but also isolated and terrified. The oppressor in me is my inner critic. Confronting the oppressor outside means also confronting the one within. The scope of this work is not navel-gazing, guilt, or a shallow helping others. It is: to “initiate a healing process toward freedom and justice.”

The goal of theatre of the oppressed though, is to offer strategies, not solutions. So what makes this role true for me? What part of our oppressive society have I taken in and do I play against myself and others? How do I overcome those roles?

The more I work on my within, the more I walk and work more boldy in the world.

Photo by em_diesus

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Internalized Oppression

There once was a little girl named Folasi; she was lively and loved to sing, dance, run and breathe. She built a home for herself in the forest. It was a cardboard box with cut-out windows decorated with colorful paint and leaves. To her, it was a mansion. On the days in which a soft breeze would come through, she could sit in her home and feel protected.

Folasi invited her friends one by one, to see her home in the forest.

When Sata came, they sang magical melodies that imitated the birds. The birds gathered around them to teach them new melodies.

When Dan came, they danced to imitate the leaves and the tall trees began to sway with them.

When Peta came, they painted from morning to nightfall. The colors of the forest became vivid: the misty brown of the ground, and the deep dark brown of the tree trunks, the yellow-green of new leaves and deeper green of older ones, the light blue of the afternoon sky and the yellow, red, and purple shades of the sunset.

When Rara came, they ran from one edge of the forest to the other and squirrels and rabbits would follow them. Rara ran fast ahead of Folasi and it was hard for her to keep up. They would lie in the grass and explode in laughter as their chests rose and fell, out of precious breath.

When Bibi came, they sat still in the middle of a circle of trees and breathed in deeply the clean air. They would turn one at a time in the direction of each tree to see and feel the uniqueness of each one. In the silence, the trees whispered in their ears. “Come play when it rains,” Mr. Maple would say. “Never stop playing,” Mrs. Sequoia would say.

After all her friends had visited, Folasi decided to go back to her home in the forest alone to plan a way to keep her happiness forever. She went back to the forest for five days.

On the first day, she fell asleep and had a dream. A huge brown goat came and wiped out her home in the forest. She woke up crying and relieved; it was just a dream. Then Folasi realized that Sata’s skin was brown like the goat and she decided it must have been a sign. Sata was no longer welcome to her home in the forest.

On the second day, Folasi was scared to have another bad dream, but she was bored with no one to sing, dance, play, run, or breathe with. So she closed all the windows and doors to feel safe and fell fast asleep. This time she dreamt that a strong wind swirled in circles and lifted up the home in the direction of the setting sun. She chased the home trying to catch it, but it flew faster than she could run and the sun was blinding her. Folasi woke up frightened, but relieved that her home was still safe. However, she then realized that the wind in her dream blew her house in the same direction that Rara ran the day they played and she could not keep up. It must be a sign. Rara would not be welcomed back.

And so it was the following three days as well. Day after day, Folasi had a bad dream about her home being destroyed. She saw similarities between each threat and each friend and one by one, she decided she would not let them come back.

On the seventh day, Folasi came back to the forest. She was confident with her plan to protect her happiness. She was satisfied and thanked the trees for their guidance. She slept again.

Now that she felt safe, Folasi had beautiful dreams. She dreamt of long days singing in her home and fun days painting. She dreamt of dancing with the trees and breathing in their love. She slept several days and nights.

Then she woke to a cold shiver. She reached for a blanket, but there was none.

She groggily opened her eyes and was terrified by what she saw. The colors of the forest were all gone. The leaves had disappeared and the branches were bare. A cold freezing breeze came through. A layer of snow covered the ground. Suddenly she was cold, frightened, and alone. She couldn’t run because the strong wind would blow her home away, and she was too sad to dance. Her paints had dried up and her voice was hoarse.

All she could do, Folasi decided, was to sit and breathe.

“Maybe Mr. Maple can tell me what is going on,” she thought.

It was hard to sit and breathe. The wind was cold, bitterness in her nostrils. Breathing was all she could do. Determined, Folasi sat. She took three breaths and asked Mr. Maple for guidance.

“Mr. Maple! Mr. Maple! Can you help me? I had all these signs and I followed them to protect my home. But then I woke up and all the leaves are gone. And one small breath of this strong cold wind will destroy my home. What shall I do?”

Mr. Maple did not reply.

She breathed ten more breaths. Deeper, deeper still, ten more, twenty more.

Finally Mr. Maple began to talk as if awoken from a deep dream.

“My-ch-ild. It is not time for questions. It is time for sleep. Go to your home outside of the forest until the season of the winds ceases.”

Folasi cried, and cried, and cried. She thought her happiness in the forest was gone forever.

She started walking in the snow towards her brick home, shivering and crying. It began to snow and she got colder and colder. She decided to seek refuge in Mrs. Sequoia’s hollow trunk.

“Hello Mrs. Sequoia! Can I come inside of your trunk? It’s cold!” she asked.

She heard no answer, but stepped inside anyway.

Slowly, the shelter helped. The trunk was wide enough for her to sit. The sides of the trunk hugged her softly. She decided to breathe deeper. The snow outside blew stronger as a storm rose. She felt warmer and safe.

At a strong gust of wind, the trunk swayed gently. Folasi heard a loud yawn.

“Ahhhhh! Hello little one! What are you doing here?” said Mrs. Sequoia. Her voice was groggy, but soft, strong, and tender.

“Hello Mrs. Sequoia! I came inside because it’s too cold. Can I stay please?”

“What happened to you little one?” said Mrs. Sequoia.

Folasi told Mrs. Sequoia about her box and her futile attempts of protecting it. The unexpected cold winds came and sabotaged her home anyway. She explained how Mr. Maple told her to leave. Folasi thought her fun times in the forest were lost forever.

“Oh! That cranky old buzzard!” said Mrs. Sequoia. “He certainly could have explained some things to you! When he is sleeping he cares about no one but himself! Of course you can stay, my child, and there is no need to cry. The cold, the ‘season of the winds,’ as Mr. Maple called it, only lasts a few months. Then, you see, the spring will come again, and before you know it, all the things you loved about the forest will be back. The birds, the warm sun, the leaves, the heat of the ground, it will all be back in no time! Nothing is lost; it is simply hidden to the eye.”

Folasi perked her head for the first time in hours. “You mean I will be able to play in the forest again?”

“Of course my sweetie!” Mrs. Sequoia laughed a deep belly laugh. The whole tree swayed with the contagious chuckle. Folasi laughed too.

“Well, what shall I do now?” Folasi asked.

“As soon as the storm settles, go to your home outside the forest,” said Mrs. Sequoia, “and go back to your friends. They are not enemies. If you had kept your friends, you would have been safer in the forest. Instead, by pushing them away, you are now caught in the storm…alone. You see my dear, with friends and loved ones near, you can weather any storm: the storms you expect and the ones that surprise you in the night. Love is the greatest gift of life. It keeps you safe.”

“But don’t I have to protect the things I love?”

“Awwww….many make this mistake, you see, my dear, protection is like the river’s water. Water must flow freely to keep its quality. If you trap it, it becomes stagnant. When water doesn’t flow, it becomes a swamp and breeds disease…with those nasty mosquitoes that bite you! Love must flow freely. It is the paradox of life: you lost your home when you tried to protect it!

Love and stay open through the storms and you will always be protected. When you love, you may be hurt, but no real harm can come to you. One may betray you, but ten more will honor you. As the flow of the river that changes course, some drops stay in the original path, while others join the new adventure.

For now, rest my child. I will wake you when it is safe for you to walk home.”

Folasi slept a warm sleep, protected by her friend, Mrs. Sequoia. The following spring, she and her friends came back to the forest and built a home of sticks and logs to prepare for the winter. That year, they played in the forest even in the snow.

Recent Comments