by Rita Fierro | Dec 5, 2019 | Facilitation, Inclusive Conversations, Participatory Leadership, Racism, Uncategorized

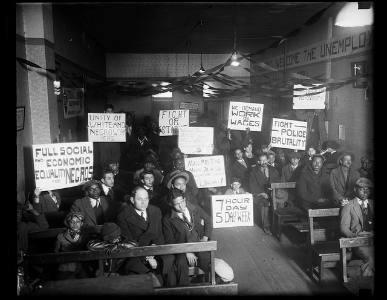

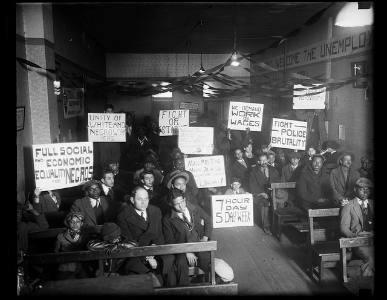

On Wednesday, we found out that Donald J Trump is our president-elect. I spent the day grieving for what I thought the next ten years of my life would look like, for me and the children I’d like to bring into the world. Outrage got him elected. Outrage now grows in those of us who have begun marching. I spent the campaign season reassuring myself that 60 years of desegregation, activism, and coalition building could not have happened in vain. That we were a better people, a more united people, than it seemed. That the violence, the hate, was the minority of us, and Trump’s campaign would become just a bad dream. I was wrong.

The violence is rising.

When I guide groups through frustration and outrage, I say it’s time to tend to the margins. In this case, the margins have become 50% of the popular vote.

For our series on inclusive conversations (conversations where differences are seen as an opportunity, not a threat), tip #7: Look for wisdom in the outrage.

I support groups of people to agree on a future direction, even large groups of people.

It’s a process that sometimes happens quickly and sometimes takes months. In each and every process, there is always a moment, when the frustration and the anger turn up. Often, I get blamed.

“Rita, you are not the right person to do this.”

“Rita, I have no idea what you want from us.”

“Rita, I’m lost.”

“Rita, you were too ‘woo woo’ in that meeting, Black folk do healing differently.”

“Rita, you are blaming me for your lack of skills.”

I said I support groups towards a common decision, I didn’t say it was easy. Often, the frustration gets directed at me. Things get delicate.

It is very hard not to react when attacked. It’s extremely hard to keep listening when I disagree with the accusations and my own emotions are triggered. But I know from experience that when the frustration shows up, it’s time to tend to the margins.

First, this means taking the time to listen to the perspective of the person/people who has/have a different opinion and really, really, taking the time to understand it. That process can take a phone call, two, or three, a lunch or more. I try my best to not take personally whatever the accusation is, but to truly listen to understand.

Second, when I’m alone again, I lick my wounds. Again, I didn’t say it was easy. I didn’t say the accusations don’t hurt. And some days are better than others. I can’t deeply listen to others unless I listen deeply to myself. I spend time thinking about how I was affected by the interactions. Did the accusations get to me? Why? Are they a projection of my own thoughts about myself?

Third, I do some thinking and processing about the conversations I had. I may call a colleague for insights. I am actively looking for the wisdom that the frustrated person or subgroup carries for the whole group. In group relations theory, every individual holds something for the whole group. It could be an emotion, and/or experience. Discovering this pearl of wisdom means finding what the individual is holding for the whole group, which helps veer away from scapegoating the person/group who disagrees. I’m not talking about looking for a compromise. I’m talking about listening to the wisdom in the outrage. The wisdom in the outrageous. Digging deeper for a kernel that will change the whole group’s dynamic from conflict to shared purpose.

Fourth, ONLY once I’m clear of what the wisdom is, I start a separate group of conversations to identify solutions. In tending to the margins, it’s important to not look for solutions too soon. Sometimes I call the frustrated folks back. Sometimes I make a small adjustment in the process, to incorporate the critical opinions. Sometimes a radical change of direction is needed.

To people on the outside, tending to the margins looks like pure magic. “How did you do that? How did you get everyone on board?” I hear this time and time again. I’ve seen the person/people in the group that others labeled difficult, come around once they saw their concerns listened to and incorporated in the future direction of the group. The others are stunned that an agreement was reached at all.

***

Tending to the margins is hard right now. Trump and trumpers stand for everything my America, focused on inclusion, is not. Yet listening, deeply listening to the frustration of the America that voted for him is really important right now. Especially, but not only for white folk. We need to listen, not agree, but listen. Otto Scharmer called it understanding the blind spot that has created this condition.

I’m one of those white people who function in predominantly Black spaces. The white spaces I navigate tend to be progressive ones. I don’t interact much with conservatives these days.

I’m feeling a real strong need to understand, to find the wisdom, in what seems like retro insanity. Is it that poor, rural, white America feels despised and dismissed by a country dominated by the urban coastal cities? That a country that governs from the coasts and dismisses the majority of its landmass is unsustainable? Our electoral college supports our coastal privilege? Is it that in our strife for diversity and inclusion, we underestimate how hard the white poor has been hit? Is it that we spend too much time despising our own instead of organizing our own? Is it that we are using white supremacy divide and conquer tools ourselves every time we use the term “hick” or “white trash”? Have we failed to build class alliances? Too much time on our phones at Sunday dinner? That the white poor continues to support racism in bad faith? In good faith? Maybe all of this or much more. Many pundits are writing articles on all of this, as I too write. I’m not calling upon you to read more articles, though you may choose to. I’m calling on you to face those who don’t think like you with genuine curiousity. I’m launching into the next week with this intention. I hope some trumpers set a similar intention for their interactions with me. It’s important I step into this work, becuse given the rising hostility, it’s even harder for my brother and sisters of color right now.

There’s wisdom in this mess for our nation. My process with groups teaches me that. Even on the discouraged days I least believe in a shared purpose, I still know it’s possible. I must look for the wisdom in the outrage, the kernel that will change that can unite us in spite of what we are experiencing right now.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Participatory Leadership

My colleague, Alissa Schwartz dreamed in her sleep about a new facilitation structure where a group narrates its history. In a circle, ordered from youngest to oldest, each person shares everything they know about the group’s history. The mystery unfolds as the elders speak towards the end. In this blog I share an experience in which I applied this process.

***

Within three weeks of Alissa sharing with me her dream, I had the opportunity to apply her structure twice! I was evaluating a consortium that supports African civil society organizations with Encompass a fellow facilitation, evaluation, and training company. The history of the consortium was very complex. Even by reviewing existing documentation, we had challenges understanding how approaches shifted over time.

At two meetings with multiple stakeholders, I facilitated History Circles. I made three modifications to Alissa’s design:

- I asked participants to order themselves from youngest to oldest in terms of their organizational membership and/or knowledge (instead of actual age);

- I allowed people who had already spoken to build upon someone else’s information, if they had forgotten to say something during their turn; and

- I sat at the center of the circle and graphic recorded their history on a timeline.

During the first meeting in Boston, the structure worked beautifully. The first people who spoke had the most simplistic views of the consortium’s history and described the moment they received their American funding as the beginning of the process. The last three people to speak carried the most knowledge and offered many stories about how the process began in Africa, among organizers, before any funding was received. The younger members listened with interest, and participants extended the storytelling during lunch, listening to an elder describe the consortium’s earlier years. It was a modern adaption of a traditional circle of elders. The total process lasted a little less than two hours.

I repeated the process in a meeting in Togo in West Africa. This time, it took only an hour, as most members were new to the consortium and had little to recount. For most participants, however, the pace of the structure was too slow, maybe because they were younger and more lively than members of the first group. Yet, participants appreciated the process of learning about their organizational history.

One African participant said: “This exercise is very helpful. We focus on the job and what people expect of us, and we don’t spend time on the history. This inspires us that when a tree grows, it gives flowers.”

The storytelling circle process has many strengths:

- It allows an outsider to hear most of the organizational or community history at one sitting;

- It allows the group to create a collective narrative of its own history;

- It supports a group reflection of a shared growth process; and

- It fosters awareness in the group of historical misinformation, as the newer members speak first, often sharing misperceptions that later get corrected when the “elders” speak.

I found three challenges to emerge during the process:

- Pace. Depending on the number of people involved, it can take a lot of time. It is also hard to time-manage individual contributions;

- Debrief. Once the last person is done talking, many participants are ready to take a break and do not want to continue in conversation; and

- Documentation. Corrections are made throughout the process, and as a graphic recorder or note-taker, you never know what will emerge from each person’s account.

Here’s what I did to overcome these challenges:

- Pace. The process works best with 10-12 people, at most. Remind participants not to repeat what has already been said;

- Debrief. After a break, I facilitated a quick-paced world café with 10 minutes per round; and

- Documentation. Before I began, I drew a timeline. As I recorded, I color-coded reoccurring information, such as meetings, problems, agreements, and practice.

We welcome other ideas about how to use and adapt a Storytelling History methodology. Try it out for yourself!

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Participatory Leadership, Racism

Many facilitation processes completely ignore power dynamics and their effect on group conversations. At best, power differentials are identified ahead of time but not addressed as interactions occur. This blog lists some of the ways that Art of Hosting plans for differences in power among participants. It also narrates a combination of processes implemented for this specific purpose.

In Art of Hosting, we learn to plan for power differentials by choosing in advance the best conversational technology for a specific need. Some ways to address power differential prior to hosting a conversation are:

- Assembling a diverse calling team: Ensuring that the team that crafts the event’s invitation is diverse will more likely attract a diversity in the participants;

- Setting the tone: Hosting a space of openness, welcoming all perspectives, and emphasizing that collective intelligence draws from the strength of multiple perspectives is key;

- Hosts developing an in-depth understanding of the event’s context ahead of time:Hosts should talk with the client and other key stakeholders about about group dynamics, priorities, and intentions;

- Choosing the appropriate technology and order of technologies: Hosts select the technologies by keeping in mind how the dynamics in the room may play out in relation to the intent of the event.

Yet, even in taking these steps, power dynamics occurring during conversational interactions are not addressed. For example, I’ve noticed in World Café and Open Space processes how some participants dominate while others choose to be quiet. Having done work with groups to help them overcome the limitations of their power dynamics, I’m frustrated at the lack of opportunities to debrief how power dynamics show up in many facilitation and participatory leadership technologies.

For this reason, Alissa and I created a conversational technology we call the Power Café, which we practiced at the Alternate Roots conference in North Carolina last August. This conference brought together artists and activists focused on social justice, and Alternate Roots has invested many years addressing racial and gender inequity within diverse groups. We had planned the process for an audience that was diverse along ethnic, racial, age, gender, and class lines. At the last moment, we were informed that another power dynamic would be added to our room. Representatives from foundations were coming to participate in the daily events as well.

What We Did (total 2.5 hours)

- In a circle, we led a quick step-forward/step-back activity identifying people’s roles and personal identities. This ensured that everyone in the room knew the range of diversities among us.

- We gave a teach-in about the emotional and practical challenges to collaboration among social activists.

- We hosted a two-round World Café in which the driving questions were emotions-based: What is Alternate Roots feeling right now? What are you feeling right now?

- After the Café, we asked participants to pair-up with someone with whom they felt comfortable talking about power dynamics. We gave each pair a list of questions to help them reflect on how power dynamics emerged in the World Café.

- Alissa and I put on big hats labelled “Provocateur” to remind participants we were changing our role. We told participants we would push them to be more critical in their exchanges. We also warned them that because we were rotating among groups, we wouldn’t necessarily be aware of everything they were talking about. It was up to them whether to welcome our comments or dismiss them.

We asked provocative questions: Did she behave that way because she’s white? Does he think he’s smarter because he’s older? Does class have something to do with this? Does race play a role here?

We ended in a closing circle where participants shared an insight they gained from their time in pairs or during the Cafe. Guiding questions included: What did you notice? What do you need? What can you offer?

What Happened

- We had a diverse group in all the ways we had expected, and participants were aware of the differences among them prior to engaging in conversation;

- Most content that emerged from the Café was about racial dynamics and the challenges that their community was facing in tending to the tensions arising from current events (Trayvon Martin and the Civil Rights Amendment were currently in the news), while spending time together;

- During the report-back from the Café, a white woman started crying, expressing her sense of being overwhelmed and wanting injustice to end, worldwide. We adjusted our time limits to offer her extra time for comfort and compassion from the group, and moved on when her experience threatened to dominate the rest of the group’s needs;

- When it came time for the pairs to form, an older male of color who was a funder wanted to pair up with a younger Native American woman, who was avoiding him. We noticed her dissenting body language and paired her up with someone else. We paired the man up with an older white woman who was one of the founders of Alternate Roots and comfortable in this “turf”;

- One woman who was especially quiet in the Café was quite vociferous in her pair. It was effective to alternate small group and large group activities;

- Participants mentioned (as we did, as well) that our positionality as two white women hosting social justice conversations was problematic, but we still worked effectively in helping some conversations take place and offering effective tools to do so.

Overall, the methodology worked well, and we are looking forward to new opportunities to practice it!

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Participatory Leadership, Program Evaluation

I’ve been integrating Participatory Leadership practices with Evaluation for years now. It started simply as a way to bring two passions together. After systematic reflection, blogging, proposal writing, co-editing a journal issue (New Directions in Evaluation, Spring 2016), and teaching trainings on building the bridge between evaluation and facilitation, I have become a lot more aware of the critical importance of this bridge for evaluation practice in service to our changing world.

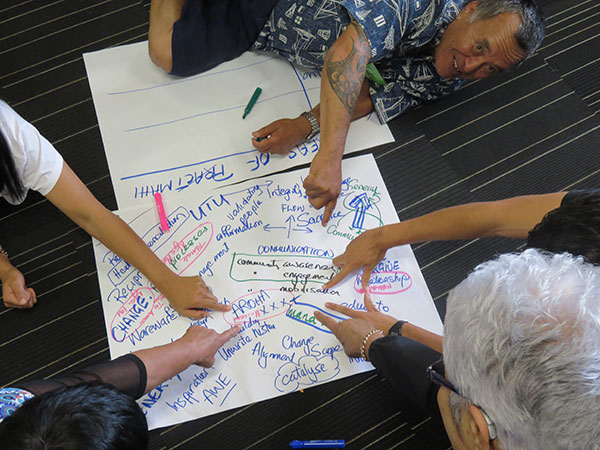

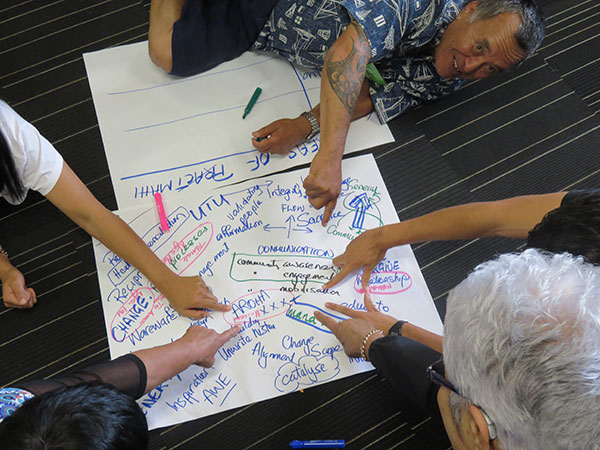

A drug and alcohol prevention network uses participatory leadership to help identify priority work areas in Auckland, NZ.

- Creating a Positive and Future Forming Reality. Participatory Leadership practices help shape the future in terms of possibilities and opportunities. As Gergen (2014) points out, if research does not take an active role in helping participants envision new, innovative, and positive collective realities, then our research methods only mirror back a negative view of current reality, de facto supporting the status quo. With its focus on collective intelligence, participatory innovation, emergence, shared decisions, and shared ownership, Participatory Leadership practices are future forming. They help groups identify powerful questions to inspire, move forward, and overcome challenges. I use evaluative tools to document that movement forward. I also use facilitation tools that in the Art of Hosting community are called harvesting tools (graphic recording, video recording, mind mapping, notes of conversations, doodles, post-its, etc.) to show what took place and what decisions were made.

- Local People (Stakeholders) Drive the Agenda. In most evaluations, even participatory evaluations, evaluation capacity building, and democratic evaluations, the evaluator generally decides in which phases of the evaluation process stakeholders will participate: evaluation questions, design, purpose, methodology, methods, or reporting. Participatory Leadership practices can be used to allocate more space for the needs of local people to drive the agenda of conversations that precede planning by answering the following questions: 1) What conversation does the group need to have to be strengthened in their purpose, collective work, and effectiveness? 2) How can we use the evaluation to hold the space for these inspiring conversations? 3) What evaluation and harvesting practices can we use to document these conversations?

- Building Dialogic Capacity. Participatory Leadership practices and theories help us reflect on the pitfalls of oppositional talking, or debating, and the creative power of true dialogue. We challenge participants to move beyond oppositional dialogue into deeper listening and creative conversations. In doing so, the group’s builds its capacity to engage in genuine, creative, and generative dialogue.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage in storytelling in Christ Church, NZ.

- Culturally Affirming. While there are evaluators who work all around the world in a variety of cultural contexts, the theory and practice of evaluation are still dominated by Western worldviews. For the non-believer, the evaluation language can often come across as linear, cold, distant, emotionless, complicated, rigid, and somewhat out of reach. While participatory evaluation and capacity building evaluation use activities to make evaluation more approachable, Participatory Leadership practices focus on the atmosphere we create in our meetings: a welcoming, more heartfelt environment where different cultures are welcomed and have more freedom to be who they are. I wouldn’t say that Participatory Leadership is culture-free, yet it isn’t as tightly constrained and culturally prescriptive as other approaches (timeframes are flexible, agendas shift depend on participants’ reactions, participants have space to raise their own issues or start their own conversations). There is more space for counternarratives to be told (more detail on this to follow in another blog).

- Advocate Inclusion and Involve Large Groups in the Design. Participatory evaluations typically involve small groups because many believe that the more people involved, the harder it is to reach decisions. Participatory Leadership practices enable us to work with large groups using relatively minimal resources and generate meaningful information to inform evaluation design and practice. For instance, a skilled group of facilitators can conduct a World Café or Open Space with 150 people in 2-3 hours to inform the Evaluation design. Some Democratic Evaluations also involve larger groups, because the evaluators are trained in dialogue and deliberation.

- Hosting Polarities and Power differences. In my experience, management can gatekeep and ostracize participation in decision-making more because they lack the skillset to handle opposite opinions productively than for ill intent. Participatory Leadership practices help the evaluator prepare for, plan for, and host dynamic tensions and power differences in a way that is both respectful of all individual parties and productive to the group.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage at the AEA conference in Denver, CO .

- Holding Space for Complexity. Using the Cynefin Framework as a point of reference, the comfort zone of an evaluator, generically speaking, is most likely to be the realm of the complicated. Our logic models are generally created, tested, and validated with complicated frameworks in mind: several causes generate several effects, in a mixture of linear and non-linear ways. However, the contextual factors and external factors in our logic model designs are areas of complexity that are often listed, but not deeply investigated. Participatory Leadership practices allow space for the investigation of the complex within our evaluation designs in a way that is meaningful and productive to other aspects of our work.

Our world is changing rapidly. If it is true that there is an unsustainable, self-destructive trend in our world, it is also true that there is another one: innovation, cooperation, and community-building. Participatory Leadership can bring tremendous strengths to our evaluation practices as it incorporates skills to engage groups and communities in an inspiring way around what to do with the current struggles of our world. In doing so, Participatory Leadership trains us to see the potential in the unknown, the emergent, the unclear, the out-of-control. And as long as we are dealing with human beings, the unknown, the unclear, and the unpredictable is always near. We can try to control it, just to satisfy our own compulsion and need for a security blanket. Or, we can immerse ourselves in the transformation and put our evaluation skillsets at the service of conversations that people need to have in a changing world.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Inclusive Conversations, Participatory Leadership

In the last blog, I listed a self-care tip for having inclusive conversations: choosing when and where to invest your energy. Inclusive conversations are conversations where differences are seen as a resource instead of a threat. These conversations can be tricky because differences can bring up fear, hurt, or anger.

Today’s tip is also about self-care. If you’re not taking care of yourself in a conversation, or hosting yourself, and being present, as the Art of hosting’s four-fold practice would put it, then it’s unlikely that the conversation will be productive. Inclusive conversations are often hard and courageous conversations. So today’s tip: Look for allies and build support before you jump in.

I used to think I had to always speak out against any injustice, prejudice, and imperfection to be a worthy activist. Once, I was a member of a mixed activist group. The leadership was all white while most of the activists were African American. I demanded the leadership confront its own privilege and stop gatekeeping opportunities for a more diverse leadership. In a public meeting, designed just for this purpose, the leadership attacked me and attempted to taint my character. No one stood up for me. When I looked around the room, I was alone. I had no allies.

Two painful months later, one of the activists contacted me. “At the time,” she said, “I didn’t know what you meant by “gatekeeping,” but now I understand. Sorry I wasn’t ready to support you and stand up to the leadership.” See, she didn’t know because I had not built my support network. I learned from the experience that slamming my head against the wall of authority and power is not activism, it’s masochism. One is more likely to burn-out this way. It took me years to recover from the experience. I was scapegoated other times in a variety of groups, until I understood how scapegoating works and what I was doing to help it.

Scapegoating is a common group dynamic. When uncomfortable feelings arise in a group, there is a tendency to project those feelings against the person who inspired them. Truth-tellers are easy scapegoats because they say things that others try to hide. People who are very empathic are most susceptible to being scapegoated, because they can unintentionally take on the emotions of the group. By blaming the scapegoat, the group can avoid facing its own feelings of fear, discomfort, and hurt. Those feelings are projected to the scapegoat.

Scapegoating is not a right-wing thing, though we are hearing a lot of it in this presidential race. I’ve been scapegoated among conservative circles, liberal artists, radical hipster anti-racism activists, and preppy extra-educated psychologists. Scapegoating is everywhere. Just start noticing in any community how the gossip is concentrated against 1-2 people. Ladies and gentlemen, those are the scapegoats.

If you’re interested in knowing more about scapegoating and group dynamics, let me know and I’ll be happy to write more. Those of us who become scapegoats, experienced it first in our own families. A group relations conference helped me see this and set this painful experience to rest once and for all. But that’s a much longer story. For now, I just want to mention one easy tip.

Since I now know my tendency to be scapegoated, as soon as I enter a new group, I take some time to build relationships and get to know the people around me. I’m intentionally looking for allies. I’m intentionally building a support system for myself and others. I’m also learning what is perceived as “normal” in this group. I try to not step into conversations about power and privilege before I have a clear understanding of who this group is, how many people share my views, and who speaks truth to power and can offer me support.

Not pushing the envelope too soon has another effect, it helps me host the group, the fourth step in the four-fold practice, in Art of hosting terms. In other words, it helps me learn the group culture, see where the group is, get a sense of where it is going, and choose the most strategic time to make a controversial comment.

You think this is an easy cop-out? Think twice. Allies and timing are strategic. If a group is ready to be challenged and go deeper, it will be less willing to scapegoat you and your contribution can be more transformative. If you choose to oppose the larger group, doing it with allies by your side can be more effective because a group of people acting in unity are harder to scapegoat.

The newly arrived, isolated person who is quick to question what is normal for the group is the easiest scapegoat ever. These days, before I choose to do this, it better be worth it.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Participatory Leadership, Trauma Transformation, Uncategorized

When most people think about trauma, they think about how individuals experience physically or emotionally violent circumstances that leave them traumatized. Traumatic experiences are painful, but can be transformative, too. Personal healing is transformative when we release shame, blame, and guilt, and allow the traumatic experience to be integrated into the rest of our lives. The same goes for groups. When trauma occurs in groups, both the individual and the group can learn from it. Welcome to my new blog series: Trauma is a two-way street.

When a person experiences trauma it affects how they interact in all the groups they belong to. Conflict, dishonesty, and challenges among groups, I argue, are most often rooted in trauma, both individual and collective. In group dynamics too, trauma is not just an obstacle, it is an opportunity for transformation. The group can strengthen its bond and its commitment to its shared work when trauma is understood, transformed, and integrated into the group’s experience of itself.

Take scapegoating, for instance. People who have been emotionally, physically, or sexually abused as children, often develop a sense of isolation in their families. They feel that they’ve never been protected and safe. As a result, they learn to fend for themselves, and are often looking out for the next attacker or betrayer, developing a distrust in people, and especially groups. They can also become very independent and self-reliant, ready to speak their minds and be successful despite the lack of support. In group, this combination of factors often translates into being a truthteller without building supportive relationships. Groups often react negatively to people who do this, especially when that truth is being avoided.

So the group blames the individual for disrupting the group’s flow and the individual is scapegoated. If individual leaves, the group is likely to do the same to the next person. When the person leaves, they experience the same thing in the next group they join. When both sides avoid truths about themselves, the dynamic is repeated in a painful, disempowering way.

But scapegoating can become an opportunity to transform trauma, instead. Let’s see how.

I wrote Avoid Being Scapegoated: Look for Allies and Build Support a couple of years ago. In this blog, I’m focusing on how scapegoating affects groups and what both the individual being scapegoated and the group can do about the experience to transform the trauma.

What the person being scapegoated can do:

– Take ownership of your need to heal your own emotional wounds. Discover your first experiences being scapegoated (generally in the family), and do whatever you need (journal, release the emotions, create art, etc.) to heal them. If the emotions are very intense, you may want to support seek out support from a professional: energy-worker, acupuncturist, massage therapist, or a psycho-therapist. You may consider taking a break from the group while you do this.

- – Say that you feel scapegoated: “I feel I’m being scapegoated for speaking my truth.”

- – Shift the attention away from yourself: “Can the group honestly say I am the only person that feels this way? I am the only one that sees what is happening as problematic? I hear you say that your concern is that ____. I’m curious to know if others agree with you or there are other perspectives as well.””

- – Build Allies and support. Before attending other meetings, ask people you trust about their thoughts and request their support: “Since you also think/feel about about this the way I do, the next time people gang up on me, could you please speak up?”

- – Restate your commitment to the group, and move the conversation forward: “My commitment is to contribute to this group fulfilling its intention to_____. Can you see that my comment comes within this commitment? Can you hear it so we can learn and move beyond it instead of getting stuck in it? Can we take a step back, and think about what’s next?”

What the group/group facilitator can do:

- – Identify the issue creating the scapegoating and ask the group to own how they contribute to it: “What does everyone else think/feel about this issue?”

- – Make space to learn from the conversation: “I’m grateful this was brought to our attention. What does this discussion teach us about ourselves and our work?.”

- – Support Transparency, create a space for people to share opinions privately (not everyone will speak out publicly): “ I’m happy this was brought to my attention. It’s always better to share reservations so we can handle them, instead of hiding them. Feel free to communicate privately with our leadership, too.”

- – Integrate dissent into the meeting. Choose a check-in question that allows everyone to speak to how they participate in the dissent: “Complete the sentence. What frustrates me most about this process right now is….”

- – Envision how the group can grow from the experience: “I’d like to see us grow from this conversation, what if we all became more ___ /built our capacity to ____ as a result of this conversation?”

Recent Comments