by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Program Evaluation

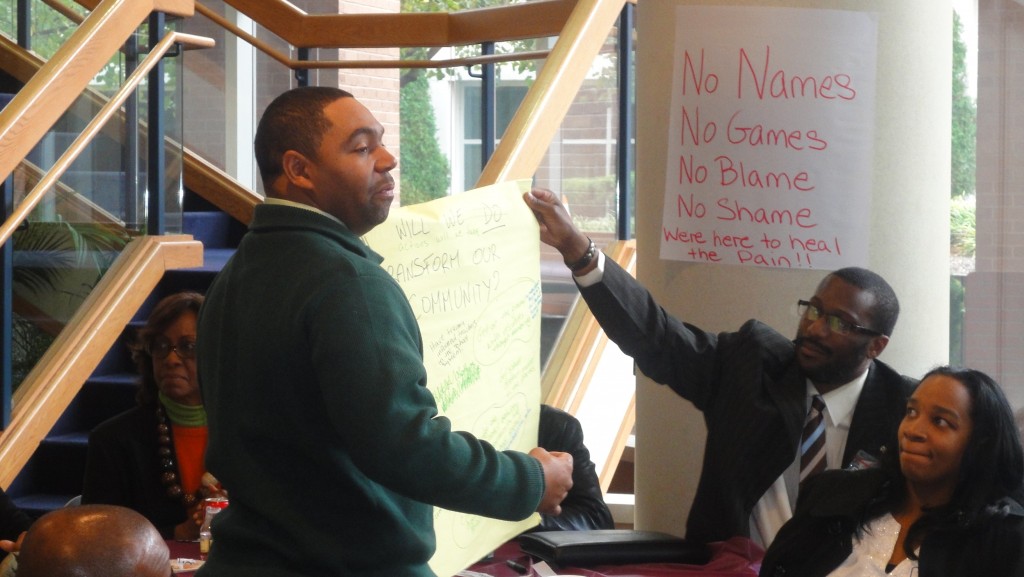

I recently was hired to help a group of people (Chester Real Change) generate a visual model that represented the transformative process they collectively experienced regarding the impact that violence had had on them.

As a participatory leadership facilitator, I worked with my client to create a structure for a retreat and questions that could meaningfully generate deep reflection. We decided we would start with personal process and then move to group work and image generation. I proposed a 20-minute individual journaling session that would encourage reflection on the following questions: What changed for you from the beginning to the end of the process? In which moment did you experience the shift? What helped the shift unfold?

In 5 minutes, participants were done and laughing and talking. Struggling to control any expressions of irritation, I asked participants to share their reflections.

“Well, I don’t like the term ‘shift’,” One participant said. “Things didn’t really shift for me. Things didn’t change; it’s just that I was having a group experience. For the first time, I got to meet other people who had to deal with violence in a different way.”

Community building in Chester, Pennsylvania

1 / 3

StartStop

“So,” I asked, “if you were to pinpoint the moment in which you felt that community, the moment in which things changed for you, when was it?”

The director of the host organization stepped in: “What I’ve learned in this process is to NOT do what you are doing, which is to contrast, simplify, and interpret other people’s answers, but to listen to different perspectives. I think she gave you the description of her experience, and you need to listen deeper and not try to change what she said.”

The handslap hurt, but was helpful and needed. I realized I had forgotten to take off my evaluator hat: I had focused on desired outcomes and pushed the conversation instead of allowing it to go where participants saw fit. Otto Scharmer in Theory U would say that I was thinking from limited past experiences instead of presencing: stepping into the possibilities of the future by sensing and connecting with it as it takes form.

Scharmer says that you sense and connect by holding an open heart and open mind. I wasn’t open enough. Generating a process for facilitation is very different than generating one for evaluation. With evaluation, you stick to a process to identify and measure desired outcomes; in facilitation, you must let go of the process and allow it to change, trusting that a vision of the future will emerge.

I was grateful for the director’s comment (and thanked him), because it allowed me to take off my evaluator hat and allow the future to take place instead of pushing and planning for it to do so. The moment in which I became aware of this I was able to hold the space for more generative listening, and I engaged participants in the active role of letting me know if the process was working for them. I checked in with participants and made many variations to our process throughout the day.

As the best meditation practices teach us, once you let go of the strong attempts to empty your mind, you may achieve that which you desire. Similarly, when I completely let go of my facilitation goal, not surprisingly, a conversation took place where we identified the image we so aspired to create.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Participatory Leadership, Program Evaluation

I’ve been integrating Participatory Leadership practices with Evaluation for years now. It started simply as a way to bring two passions together. After systematic reflection, blogging, proposal writing, co-editing a journal issue (New Directions in Evaluation, Spring 2016), and teaching trainings on building the bridge between evaluation and facilitation, I have become a lot more aware of the critical importance of this bridge for evaluation practice in service to our changing world.

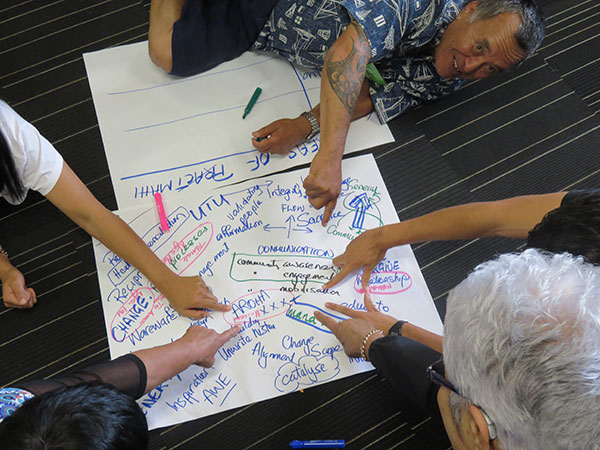

A drug and alcohol prevention network uses participatory leadership to help identify priority work areas in Auckland, NZ.

- Creating a Positive and Future Forming Reality. Participatory Leadership practices help shape the future in terms of possibilities and opportunities. As Gergen (2014) points out, if research does not take an active role in helping participants envision new, innovative, and positive collective realities, then our research methods only mirror back a negative view of current reality, de facto supporting the status quo. With its focus on collective intelligence, participatory innovation, emergence, shared decisions, and shared ownership, Participatory Leadership practices are future forming. They help groups identify powerful questions to inspire, move forward, and overcome challenges. I use evaluative tools to document that movement forward. I also use facilitation tools that in the Art of Hosting community are called harvesting tools (graphic recording, video recording, mind mapping, notes of conversations, doodles, post-its, etc.) to show what took place and what decisions were made.

- Local People (Stakeholders) Drive the Agenda. In most evaluations, even participatory evaluations, evaluation capacity building, and democratic evaluations, the evaluator generally decides in which phases of the evaluation process stakeholders will participate: evaluation questions, design, purpose, methodology, methods, or reporting. Participatory Leadership practices can be used to allocate more space for the needs of local people to drive the agenda of conversations that precede planning by answering the following questions: 1) What conversation does the group need to have to be strengthened in their purpose, collective work, and effectiveness? 2) How can we use the evaluation to hold the space for these inspiring conversations? 3) What evaluation and harvesting practices can we use to document these conversations?

- Building Dialogic Capacity. Participatory Leadership practices and theories help us reflect on the pitfalls of oppositional talking, or debating, and the creative power of true dialogue. We challenge participants to move beyond oppositional dialogue into deeper listening and creative conversations. In doing so, the group’s builds its capacity to engage in genuine, creative, and generative dialogue.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage in storytelling in Christ Church, NZ.

- Culturally Affirming. While there are evaluators who work all around the world in a variety of cultural contexts, the theory and practice of evaluation are still dominated by Western worldviews. For the non-believer, the evaluation language can often come across as linear, cold, distant, emotionless, complicated, rigid, and somewhat out of reach. While participatory evaluation and capacity building evaluation use activities to make evaluation more approachable, Participatory Leadership practices focus on the atmosphere we create in our meetings: a welcoming, more heartfelt environment where different cultures are welcomed and have more freedom to be who they are. I wouldn’t say that Participatory Leadership is culture-free, yet it isn’t as tightly constrained and culturally prescriptive as other approaches (timeframes are flexible, agendas shift depend on participants’ reactions, participants have space to raise their own issues or start their own conversations). There is more space for counternarratives to be told (more detail on this to follow in another blog).

- Advocate Inclusion and Involve Large Groups in the Design. Participatory evaluations typically involve small groups because many believe that the more people involved, the harder it is to reach decisions. Participatory Leadership practices enable us to work with large groups using relatively minimal resources and generate meaningful information to inform evaluation design and practice. For instance, a skilled group of facilitators can conduct a World Café or Open Space with 150 people in 2-3 hours to inform the Evaluation design. Some Democratic Evaluations also involve larger groups, because the evaluators are trained in dialogue and deliberation.

- Hosting Polarities and Power differences. In my experience, management can gatekeep and ostracize participation in decision-making more because they lack the skillset to handle opposite opinions productively than for ill intent. Participatory Leadership practices help the evaluator prepare for, plan for, and host dynamic tensions and power differences in a way that is both respectful of all individual parties and productive to the group.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage at the AEA conference in Denver, CO .

- Holding Space for Complexity. Using the Cynefin Framework as a point of reference, the comfort zone of an evaluator, generically speaking, is most likely to be the realm of the complicated. Our logic models are generally created, tested, and validated with complicated frameworks in mind: several causes generate several effects, in a mixture of linear and non-linear ways. However, the contextual factors and external factors in our logic model designs are areas of complexity that are often listed, but not deeply investigated. Participatory Leadership practices allow space for the investigation of the complex within our evaluation designs in a way that is meaningful and productive to other aspects of our work.

Our world is changing rapidly. If it is true that there is an unsustainable, self-destructive trend in our world, it is also true that there is another one: innovation, cooperation, and community-building. Participatory Leadership can bring tremendous strengths to our evaluation practices as it incorporates skills to engage groups and communities in an inspiring way around what to do with the current struggles of our world. In doing so, Participatory Leadership trains us to see the potential in the unknown, the emergent, the unclear, the out-of-control. And as long as we are dealing with human beings, the unknown, the unclear, and the unpredictable is always near. We can try to control it, just to satisfy our own compulsion and need for a security blanket. Or, we can immerse ourselves in the transformation and put our evaluation skillsets at the service of conversations that people need to have in a changing world.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Africa, Program Evaluation

This article appeared in the American Evaluation Association’s Feminist Issues in Evaluation Interest Group’s Newsletter on July 9, 2015 and is being republished here.

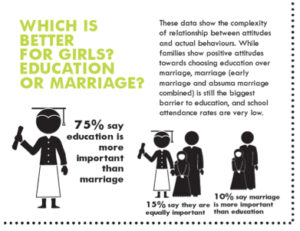

In the PAGES project for Girlhub Ethiopia, in March 2014, we explored community attitudes about girls’ education. The Afar region of Ethiopia is predominantly desert; the population is predominantly Muslim and nomadic. Most Afar people live in mobile homes made of sticks, mats, and plastic covers that are gathered into a bundle when it’s time to move.

The overall evaluation was a randomized control trial that included 3000 participants. The surveys and interviews in the overall evaluation revealed that the community had very positive attitudes towards education. When asked if children were “in school” most parents and most children said yes. School enrollment is mandatory in Ethiopia.

A subset of 100 girls and 100 female caregivers participated in our exploratory study using SenseMaker’s mixed-method storytelling methodology. Grounded in complexity theory (Cynefin Framework), SenseMaker uses more indirect and complex response items to help identify contradictions and complexity.

Here are some:

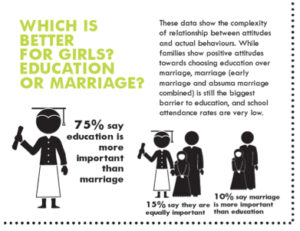

- While 75% of girls said they were “in school” only 25% attended 5 days a week.

- While 75% participants say that education is more important than marriage to improve a girls’ life, 77% of girls and 57% of caregivers say that child marriage is a barrier to girls’ education.

- While chores (which include walking 5-10 km a day to fetch water) are listed as the biggest barrier for girls’ education (84% of girls and 82% of caregivers say so). Many participants (32%) say that the family’s beliefs about education determine whether a girl goes to school.

When asked who benefits from a girls’ education, the camp is split. Some say it benefits equally the girl, the family, and the community.

Many saw it benefitting the girl first, her family at a later date, and only minimally and in the long term, the community. This perception of long-term gain over short-term gain may explain the gap between attitudes and behavior, between school enrollment and actual attendance. If you had no water to drink today, would long-term gain drive your decisions? One of the recommendations made to PAGES was to add to the school curricula topics that provide helpful information for the family and the community in the short-term, given the challenges of the Afar region.

An infographic summary of results is available online on the Fierro Consultingwebsite. The full report will be available on the Girlhub Ethiopia’s website and the Fierro Consulting website in Fall 2015.

Photo courtesy of Girlhub Ethiopia ©2013

Recent Comments