by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Facilitation, Participatory Leadership, Racism

Many facilitation processes completely ignore power dynamics and their effect on group conversations. At best, power differentials are identified ahead of time but not addressed as interactions occur. This blog lists some of the ways that Art of Hosting plans for differences in power among participants. It also narrates a combination of processes implemented for this specific purpose.

In Art of Hosting, we learn to plan for power differentials by choosing in advance the best conversational technology for a specific need. Some ways to address power differential prior to hosting a conversation are:

- Assembling a diverse calling team: Ensuring that the team that crafts the event’s invitation is diverse will more likely attract a diversity in the participants;

- Setting the tone: Hosting a space of openness, welcoming all perspectives, and emphasizing that collective intelligence draws from the strength of multiple perspectives is key;

- Hosts developing an in-depth understanding of the event’s context ahead of time:Hosts should talk with the client and other key stakeholders about about group dynamics, priorities, and intentions;

- Choosing the appropriate technology and order of technologies: Hosts select the technologies by keeping in mind how the dynamics in the room may play out in relation to the intent of the event.

Yet, even in taking these steps, power dynamics occurring during conversational interactions are not addressed. For example, I’ve noticed in World Café and Open Space processes how some participants dominate while others choose to be quiet. Having done work with groups to help them overcome the limitations of their power dynamics, I’m frustrated at the lack of opportunities to debrief how power dynamics show up in many facilitation and participatory leadership technologies.

For this reason, Alissa and I created a conversational technology we call the Power Café, which we practiced at the Alternate Roots conference in North Carolina last August. This conference brought together artists and activists focused on social justice, and Alternate Roots has invested many years addressing racial and gender inequity within diverse groups. We had planned the process for an audience that was diverse along ethnic, racial, age, gender, and class lines. At the last moment, we were informed that another power dynamic would be added to our room. Representatives from foundations were coming to participate in the daily events as well.

What We Did (total 2.5 hours)

- In a circle, we led a quick step-forward/step-back activity identifying people’s roles and personal identities. This ensured that everyone in the room knew the range of diversities among us.

- We gave a teach-in about the emotional and practical challenges to collaboration among social activists.

- We hosted a two-round World Café in which the driving questions were emotions-based: What is Alternate Roots feeling right now? What are you feeling right now?

- After the Café, we asked participants to pair-up with someone with whom they felt comfortable talking about power dynamics. We gave each pair a list of questions to help them reflect on how power dynamics emerged in the World Café.

- Alissa and I put on big hats labelled “Provocateur” to remind participants we were changing our role. We told participants we would push them to be more critical in their exchanges. We also warned them that because we were rotating among groups, we wouldn’t necessarily be aware of everything they were talking about. It was up to them whether to welcome our comments or dismiss them.

We asked provocative questions: Did she behave that way because she’s white? Does he think he’s smarter because he’s older? Does class have something to do with this? Does race play a role here?

We ended in a closing circle where participants shared an insight they gained from their time in pairs or during the Cafe. Guiding questions included: What did you notice? What do you need? What can you offer?

What Happened

- We had a diverse group in all the ways we had expected, and participants were aware of the differences among them prior to engaging in conversation;

- Most content that emerged from the Café was about racial dynamics and the challenges that their community was facing in tending to the tensions arising from current events (Trayvon Martin and the Civil Rights Amendment were currently in the news), while spending time together;

- During the report-back from the Café, a white woman started crying, expressing her sense of being overwhelmed and wanting injustice to end, worldwide. We adjusted our time limits to offer her extra time for comfort and compassion from the group, and moved on when her experience threatened to dominate the rest of the group’s needs;

- When it came time for the pairs to form, an older male of color who was a funder wanted to pair up with a younger Native American woman, who was avoiding him. We noticed her dissenting body language and paired her up with someone else. We paired the man up with an older white woman who was one of the founders of Alternate Roots and comfortable in this “turf”;

- One woman who was especially quiet in the Café was quite vociferous in her pair. It was effective to alternate small group and large group activities;

- Participants mentioned (as we did, as well) that our positionality as two white women hosting social justice conversations was problematic, but we still worked effectively in helping some conversations take place and offering effective tools to do so.

Overall, the methodology worked well, and we are looking forward to new opportunities to practice it!

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

Southern Italy is not the first place in the world where most people would turn their attention to when they think about oppression. My passion for understanding privilege and oppression in the United States and my choice to learn from African American present and past history is often puzzling to those who cannot see the link.

Ancient Norman Castle of Apice, Benevento.

1 / 6

StartStop

Well, over many centuries Southern Italy was invaded over and over again by Moors, Romans, Vandals, Normans, Slavs, Visigoths, the French, and Spaniards. This makes us a surviving people, and that’s why Italy has so many castles, arches, and other edifices – parting gifts from past invaders.

It took the Romans 53 years to get my people, the Samnites, to submit to their will. The Italian national unification movement, which created the nation of Italy in 1861, deposed our beloved and trusted southern Italian leader Garibaldi, as the northern industrial forces feared that the southern Italian agricultural workers would demand a social revolution and redistribution of land. This redistribution of land has been sought after since the Roman Empire, and is still relevant to the North-South conflict today.

Sound familiar?

There are three common internalized responses to oppression I hear a lot both in my small Southern Italian hometown of Benevento and in the predominantly Black neighborhood I live in, in the USA:

- “They won’t let us do anything.”

- “They’re jealous; as soon as you try to rise they will bring you down.”

- “You can’t do that.” (“It” can be anything from creating a workshop to a radical shift in political representation.)

These three common responses, I believe, are a strong indicator of a people who have never felt represented by their government and who have gotten accustomed to being repressed instead of encouraged.

This defeatist thinking is a hindrance to our work of building collective action. Overcoming it isn’t easy.

Carter G. Woodson, a phenomenal African American historian and thinker said it most effectively:

“When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his ‘proper place’ and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.”

I’ve done a great deal of inner-awareness work in the past years to overcome my self-sabotage and negative thinking mechanisms. I have made some progress, though I’m certainly not done. Being in Italy during the holiday season with my family while I offered seminars and workshops reminded me on a daily basis how the ongoing imposition of limiting beliefs is a way to keep oppressed people “in their place” and off the radar of innovation and world change.

It reminds me of how far I’ve come, and how much farther I need to go for positive thinking to become a default for me.

Breaking away and living in other countries may have allowed me to escape the hypnotic negative thinking of my people. I’m beginning to think that specific vibrations of internalized oppression are peculiar to a land and people, and it may be easier to live and operate within the context of oppression of a people other than one’s own. When I am in the USA, the pain I feel isn’t as paralyzing, internalized, and self-inflicted as when I’m in Benevento.

This reflection is helping me mitigate the judgment I feel about my own people that underlies my irritation with them. Reflecting on my peculiar positionality within my culture is helping me be a more compassionate daughter, role model for my cousins, and consultant in the work I am doing in Italy.

When I am in Italy and as I work with oppressed peoples around the world, I practice:

- Patience, as I recognize that it is my privilege of being able to travel that has affected the way I look at my own oppressed reality when I’m up close;

- Gratitude, as I appreciate the opportunities I’ve had to break away and live differently; and

- Compassion towards those who are still stuck in a negative-thinking cycle.

- Another view from my grandparents’ farm in Apice, the trees on the right and bordering the river.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Internalized Oppression, Racism

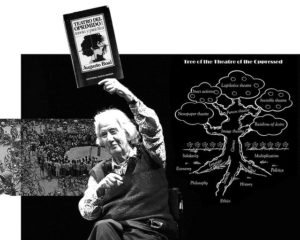

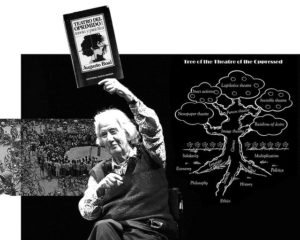

Just before this groundbreaking week, I attended a four-day Theatre of the Oppressed training for facilitators. This was my unintentional preparation for a week in which the South Carolina shooting and less-heard burning of Black churches, the Supreme court upholding of the Affordable Care Act and Gay Marriage. Whatever side you are on, the mix of these events are making our opinions about difference in America slap us in the face.

Photo by em_diesus

We can choose to do the deep work that allyship, forgiveness, and restorative justiceentail. This work is never comfortable. When we face the beast, we often want to run away. Most often this is because we discover that beast who we hate outside of us, is also within us, we have internalized it. We are not immune of the context we grew up in. I’ve learned that I no longer do this work to help others. I do it to embrace my own humanity in how I show up for others, but also how I show up for myself.

There are many different approaches to doing this “work.” One is the Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a groundbreaking way of using theatre and improvisation in groups to help people engage individually and collectively with how they have been affected by power structures and beliefs. Created by Augusto Boal, it is grounded in Paul Friere’s powerful Pedagogy of the Oppressed. By being spect-actors, simultaneously spectators and actors, participants have a chance to both reflect on a situation and offer strategies to overcome the challenges each solution presents.

I tend to take on a role in groups, one in which I challenge the group to go deeper. At times I’ve been painfully scapegoated for it. But the group in my Theatre of the Oppressed training was a singular group of people who are brave themselves and who are as passionate about facilitating conversations about power, inequity, and justice, as I am. So they welcomed my challenge and bid me higher, pushing me way out of my comfort zone.

In some small-group work, we set up a skit of a summer backyard party in which the owner, a white woman, Sally, who recently moved into the imaginary neighborhood, tells off the Black guy, Jamal, who’s lived in the neighborhood for generations, because he plays loud rap music from his car in front of her house. A friend and ally, Kate, steps in to support the Black guy and calm Sally down, but Sally is drinking. She gets louder and louder, nastier and nastier. As her sense of entitlement grows, so does her escalating rage. Here are some things she says:

“Not in my neighborhood.”

“I didn’t spend all this money to live in this neighborhood to hear that music.”

“This is why we don’t like people like you moving in.”

“What’s wrong with you people?”

“Shut that music in front of my house. This is my property.”

When Kate steps in to ask Sally to not treat her friend Jamal this way, Sally hesitates for a second, but then keeps going, even louder.

“Stop talking to me, I want the music off, NOW.”

Augusto Boal photo by LCR SAP

Kate is turned-off by the ineffectiveness of her attempt to support Jamal, she physically takes two steps back, even if she still wants to help. She doesn’t know how, the violence puts her off. Jamal is left to confront Sally. He is peaceful and brave. He offers a handshake: “I’m a neighbor, nice to meet you, can we talk about this?”

Sally barely concedes her fingertips, showing her disgust for touching him.

This was a theatre moment. But it truthfully depicts how quickly things can precipitate in our own U.S.A.

I was the one who played Sally’s role.

The instructor suggested: “Boal says there is a bit of the oppressor in all of us. I challenge you to discover what playing the oppressor will teach you.”

It has taken me two weeks to write about this powerful experience that Boal would call “the oppressor within.” The experience was as enlightening as it was horrifying. Here’s why.

- It wasn’t hard. I wanted to think of myself as such a “good person” that it would be awfully hard for me to stay in character. It wasn’t. I had a repertoire of experiences to play the role: a combination of conversations had, listened to, ways I’ve been treated, and emotional truth.

- Dismissing human beings. In Sally’s role, it wasn’t hard for me to dismiss these two human beings and anything they said to get what I wanted. What I wanted in that moment was more important than anything else. As if Jamal wasn’t a human being, he was just an obstacle to be removed.

- The ball of anger. Yelling at Jamal was like taking everything that had ever hurt me, from being made fun of in nursery school to being fired on the job, any resentment for anything I believed should not have happened to me, and channeling through, no against him. This was a spiral. Once it started, it was addictive. It was easier than I thought to let it escalate.

- The shame. After I stepped out of role, I had a deep sense of shame. I felt others more distant. Were others judging me for playing the role like I had? Were they asking themselves if this is really who I am? Is it?

- The isolation. Also after I stepped out of role, I felt so isolated, that I was questioning the foundation of my own humanity. I felt alone in the world, disconnected. I felt a sense of despair that only human contact could nurture away. John A Powell in a recent interview said “The issue of race is an issue of belonging.” In that isolation, I was terrified of not belonging anywhere. Thankfully, I know how to reach out for connection. I’ve learned to ask for help. How do the people who embody this harsh role to an extreme feel on a day-to-day basis? It brought to a tremendous sense of pity.

The oppressor in me is completely disconnected from others and my true self. The oppressor in me is judgmental, harsh, ruthless, entitled, but also isolated and terrified. The oppressor in me is my inner critic. Confronting the oppressor outside means also confronting the one within. The scope of this work is not navel-gazing, guilt, or a shallow helping others. It is: to “initiate a healing process toward freedom and justice.”

The goal of theatre of the oppressed though, is to offer strategies, not solutions. So what makes this role true for me? What part of our oppressive society have I taken in and do I play against myself and others? How do I overcome those roles?

The more I work on my within, the more I walk and work more boldy in the world.

Photo by em_diesus

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Racism, Uncategorized

African American people taught me how to live well, at peace, while feeling like a fish out of water. It hurts to watch how many people, and our media, assume that violence is norm in Black culture.

By the standards of most Americans I am an incredibly weird person. I am an Italian American woman who spent seven years studying African American culture in college, first for a Master’s in Sociology, then a PhD in African American studies. I left a life in Rome, Italy, the eternal city, to study in Philadelphia. I wish I could make a collage with the look on people’s faces, of all colors, when I tell them what I just told you.

I studied to end injustice, but I also studied to make peace with my own dual Italian American cultural heritage. I felt at odds in my own skin.

In those seven years, I did a lot more than study. I grew up, too. The journey started at 23. I got my PhD at 30. And in those seven years, I met two women, who led me, taught me, assisted me, held me, and walked with me in the path to becoming a woman. Both of these women are Black. So I joke at times that I’m an Italian American raised by Black women. Without these women, I could not be who I am. They taught me to love myself unconditionally, forgive myself, express myself, express my art, stand and walk in the world, while never fitting in.

It’s been ten years since the PhD and I’ve continued to grow. I’ve continued to listen and learn about Black folks in America. And I feel that I understand now that while my mentors are phenomenal individuals, their lessons were cultural, from a collective experience. They taught me some of what their families had taught them: how to survive in the face of incredible adversity.

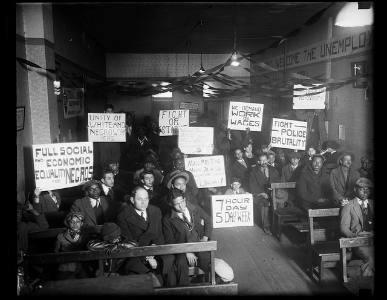

I’ve reached the conclusion that Black people are the ethical anchor of our country. Because of ongoing discrimination, in housing, education, voting, employment, health, and the criminal justice system, Black folks have needed to dig deeper into their humanity, their resources, their talents, their networks, than anyone else in order to survive America. Of course, many other people of color have experienced these challenges, too. Over the years, I felt an affinity for African American culture that made me want to know more.

To me, the reason why Black folks dominate the art world is because they’ve needed to use art to express their deepest pain, injustice, and emotions. From old spirituals to blues, Nina Simone to Miles Davis, India Arie to The Roots, art has become a vehicle for humanity, for expressing humanness, aliveness. Playing hearts, souls, and pain through the beat of drums, voices, guitars, trumpets, saxes, and basses.

I’ve traveled the world. Yet in my experiences, Black folk in America, as a people, have deeper compassions, feelings, and forgiveness than any other culture I know. They have been trying to forgive white folk for hundreds of years of injustice. They’ve been nurturing community and organizing peacefully as long as they’ve been on this land.

Dressed in Sunday’s Best

I know most white folks are scared that Black folk will become violent and attempt to turn over the social order and be on top. This has not happened and will not happen because Black folk will not do to whites what we did to them because the majority of Black folk have worked hard and work hard every day to be productive, patient, and loving. To believe that a better world is possible. To not judge the few for the actions of the many.

Spirituality upholds Black folk. The strong connection to each other, to God, to a higher power, to prayer, to whatever you want to call it, that connection has kept Black folk alive and positive for centuries. Have you noticed how in Black neighborhoods there is a church every few feet? Learning to elevate one’s heart, mind, and soul above limiting circumstances. Moving mountains with kindness. Drawing strength, never easily, from the bowels of existence, which in the words of W.E.B. DuBois “dogged strength alone keeps from being torn asunder.”

Most of us white folk are so attached to having things our way that we lack the same capacity to be positive through hardship, love through challenges, patient when times or tough, and to express when we’re in pain. Think how much you would love your neighbor if you knew that their great-grandfather had raped your great-grandmother, during slavery, and that your neighbor’s family has forgotten this, but yours has not.

How much would you love your neighbor if your neighbor’s brother also worked for the police force that killed your dad when you were 5? And your brother when he was 15, and your best friend when he was 20?

Now add on the fact that your neighbor also has better access to better healthcare, education, employment, housing, legal and political representation than you. Would you even try to love your neighbor? Would your protests against inferior access to healthcare, education, employment, and legal representation be peaceful?

It is this ability to connect with humanity, with humanness that causes white folks to be so enamored with Black music, culture, food, fashion. We white folks reach out to Blackness to connect with our own humanity.

A rally attendee on a scooter holds a sign reading Black Lives Matter at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco.

This is also why I believe when we white folk say something we know is questionable in a group conversation, we look at Black folk for a reaction. Deep down, we know Black folk are the measure of our humanity. We know they are the measure of whether what we said was fucked up.

Most Black folks are already modeling humanness with incredible compassion and grace. But we cannot demand they do what we as a country, don’t do.

Our country is a ship in the waters of ethical confusion. Black folk are the anchor. They anchor us with the deepest and most profound parts of our country’s humanity: our ability to love, to create, to forgive, to connect, to organize for justice.

The waters are getting choppy. And the captain–society, the government, white folks, our institutions–is revving the motor. How can we expect the anchor to keep the ship grounded?

Every murder is an acceleration. Every child charged as an adult is an acceleration. Every bargain deal accepted by an innocent man is an acceleration. Every person in prison because they cannot pay a fine is an acceleration. The ship cannot stay still if the acceleration continues.

It is unjust to expect Black folk to anchor our collective ship.

The chain linking the anchor to the ship is breaking.

So whomever you are, wake up. Find your humanity. Choose whether you want to keep revving the motor on our ship or demand it stop. Get involved to change the conditions that are generating this insane acceleration. Join an organization, that suits you, that is working to slow it down. There are many.

Langston Hughes described it well when he wrote:

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?…

Or does it Explode?”

Langston Hughes

***

I wrote this in response to the killings of Philando Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling by the hands of police officers. May your souls rest in peace. May your lives not be ended in vain.

Five hours after I wrote this, Micah Xavier Johnson, a Black man who had served in the United States Army in Afghanistan, earning several medals, shot 11 white police officers, killing five, in Dallas, TX.

Images:

Dressed in Sunday’s Best by Su-Chan

https://www.flickr.com/photos/su-chan/

A rally attendee on a scooter holds a sign reading Black Lives Matter at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco.

By Pax Ahimsa Gethen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50063410

Recent Comments