by Rita Fierro | Dec 5, 2019 | Facilitation, Inclusive Conversations, Participatory Leadership, Racism, Uncategorized

On Wednesday, we found out that Donald J Trump is our president-elect. I spent the day grieving for what I thought the next ten years of my life would look like, for me and the children I’d like to bring into the world. Outrage got him elected. Outrage now grows in those of us who have begun marching. I spent the campaign season reassuring myself that 60 years of desegregation, activism, and coalition building could not have happened in vain. That we were a better people, a more united people, than it seemed. That the violence, the hate, was the minority of us, and Trump’s campaign would become just a bad dream. I was wrong.

The violence is rising.

When I guide groups through frustration and outrage, I say it’s time to tend to the margins. In this case, the margins have become 50% of the popular vote.

For our series on inclusive conversations (conversations where differences are seen as an opportunity, not a threat), tip #7: Look for wisdom in the outrage.

I support groups of people to agree on a future direction, even large groups of people.

It’s a process that sometimes happens quickly and sometimes takes months. In each and every process, there is always a moment, when the frustration and the anger turn up. Often, I get blamed.

“Rita, you are not the right person to do this.”

“Rita, I have no idea what you want from us.”

“Rita, I’m lost.”

“Rita, you were too ‘woo woo’ in that meeting, Black folk do healing differently.”

“Rita, you are blaming me for your lack of skills.”

I said I support groups towards a common decision, I didn’t say it was easy. Often, the frustration gets directed at me. Things get delicate.

It is very hard not to react when attacked. It’s extremely hard to keep listening when I disagree with the accusations and my own emotions are triggered. But I know from experience that when the frustration shows up, it’s time to tend to the margins.

First, this means taking the time to listen to the perspective of the person/people who has/have a different opinion and really, really, taking the time to understand it. That process can take a phone call, two, or three, a lunch or more. I try my best to not take personally whatever the accusation is, but to truly listen to understand.

Second, when I’m alone again, I lick my wounds. Again, I didn’t say it was easy. I didn’t say the accusations don’t hurt. And some days are better than others. I can’t deeply listen to others unless I listen deeply to myself. I spend time thinking about how I was affected by the interactions. Did the accusations get to me? Why? Are they a projection of my own thoughts about myself?

Third, I do some thinking and processing about the conversations I had. I may call a colleague for insights. I am actively looking for the wisdom that the frustrated person or subgroup carries for the whole group. In group relations theory, every individual holds something for the whole group. It could be an emotion, and/or experience. Discovering this pearl of wisdom means finding what the individual is holding for the whole group, which helps veer away from scapegoating the person/group who disagrees. I’m not talking about looking for a compromise. I’m talking about listening to the wisdom in the outrage. The wisdom in the outrageous. Digging deeper for a kernel that will change the whole group’s dynamic from conflict to shared purpose.

Fourth, ONLY once I’m clear of what the wisdom is, I start a separate group of conversations to identify solutions. In tending to the margins, it’s important to not look for solutions too soon. Sometimes I call the frustrated folks back. Sometimes I make a small adjustment in the process, to incorporate the critical opinions. Sometimes a radical change of direction is needed.

To people on the outside, tending to the margins looks like pure magic. “How did you do that? How did you get everyone on board?” I hear this time and time again. I’ve seen the person/people in the group that others labeled difficult, come around once they saw their concerns listened to and incorporated in the future direction of the group. The others are stunned that an agreement was reached at all.

***

Tending to the margins is hard right now. Trump and trumpers stand for everything my America, focused on inclusion, is not. Yet listening, deeply listening to the frustration of the America that voted for him is really important right now. Especially, but not only for white folk. We need to listen, not agree, but listen. Otto Scharmer called it understanding the blind spot that has created this condition.

I’m one of those white people who function in predominantly Black spaces. The white spaces I navigate tend to be progressive ones. I don’t interact much with conservatives these days.

I’m feeling a real strong need to understand, to find the wisdom, in what seems like retro insanity. Is it that poor, rural, white America feels despised and dismissed by a country dominated by the urban coastal cities? That a country that governs from the coasts and dismisses the majority of its landmass is unsustainable? Our electoral college supports our coastal privilege? Is it that in our strife for diversity and inclusion, we underestimate how hard the white poor has been hit? Is it that we spend too much time despising our own instead of organizing our own? Is it that we are using white supremacy divide and conquer tools ourselves every time we use the term “hick” or “white trash”? Have we failed to build class alliances? Too much time on our phones at Sunday dinner? That the white poor continues to support racism in bad faith? In good faith? Maybe all of this or much more. Many pundits are writing articles on all of this, as I too write. I’m not calling upon you to read more articles, though you may choose to. I’m calling on you to face those who don’t think like you with genuine curiousity. I’m launching into the next week with this intention. I hope some trumpers set a similar intention for their interactions with me. It’s important I step into this work, becuse given the rising hostility, it’s even harder for my brother and sisters of color right now.

There’s wisdom in this mess for our nation. My process with groups teaches me that. Even on the discouraged days I least believe in a shared purpose, I still know it’s possible. I must look for the wisdom in the outrage, the kernel that will change that can unite us in spite of what we are experiencing right now.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Uncategorized

Speaking with Radical Honesty is a relatively easy practice to preach and a really hard thing to do. I first heard the phrase a few years ago, and it lingered in my mind. Our ability to hold the HARD conversations in life is a big part of what defines us. HARD conversations are as an integral part of life as are joy and love.

I once attended a ten week course hosted by a community that is very important to me and makes me feel at home. I hated the course. It was too long, too boring, and I longed for creativity and intellectual depth, but most of all I longed for warmth and heart. The teacher was tired of teaching and it showed. Throughout the ten weeks I took on different roles. First, I challenged the teacher with hard questions that got no answers, then I withdrew, then I tried to learn more about her story and connect with her. Finally, I withdrew again. Other participants in the course were also bored, but did not speak up. The ten weeks dragged.

Baby orphan elephants hugging (Nairobi, Kenya)

1 / 2

StartStop

At the end of the ten weeks, the assistant teacher spoke to me from a place of love and Radical Honesty: “It hurt when you withdrew. It felt like you thought you knew more than me, that you were superior. I felt that I failed you, that I was not a good enough instructor for you. I wanted to give you more and couldn’t. ”

The assistant teacher’s Radical Honesty drew me in. I had to admit that I did not know how to have a Radically Honest conversation with the teachers. I didn’t know how to voice my boredom and ask questions about how we could co-create a different class. I was scared of being judged for wanting different things and seeing things differently.

Often, the things that most need to be said are hard to say and hard to hear. How you handle the elephants in a room is a big part of how you show up in a workplace.

Some people keep an elephant in its place and never mention it. They feed the elephant while denying its obvious presence, silently leaving mounds of food and milk in the middle of the room. Other times, people scream to the world that the elephant is standing right there, while everyone else around them pretends not to see it.

There is another way to handle unacknowledged tensions in a room: asking questions with curiosity and wonder. “Hmmmm,” says the wise one, “I wonder where the food that you laid at the center of the room went yesterday? It’s no longer there.” Slowly and delicately we engage with others and overcome the resistance to naming what is in the room. I did this in a final conversation with my teacher by asking her what aspect of teaching brought her enthusiasm. “I don’t know,” she answered.

It takes courage to welcome Radical Honesty as an opportunity for growth, and you’ll never know exactly how you’ll grow from it. Sometimes a relationship can stumble over a challenging conversation and shoot up afterwards like a rocket –sudden, immediate, strong, impressive.

The teacher and I never became close, but the teaching assistant and I did. In our Radically Honest conversation, we each held the best and most tender parts of ourselves.

These conversations are not for the faint of heart, and they are also not for every relationship. They take time and commitment.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Inclusive Conversations, Uncategorized

“What is it about you Americans?” a friend in New Zealand said to me a few months ago, “Why are you so resistant to the common good?” The state of panic, fomented by some presidential candidates, reminds me of that statement. Inclusive conversations are defined as conversations where differences are leveraged as a resource, not a threat. For this issue, I’m addressing practicing inclusion for our common good.

What is the “common good?” It is something that affects all of us humans as human. Right now, the political landscape has become polarized because it is fear-driven, it helps us forget that we have anything in common. People rush to push others away in order to offer an illusion of protection. If only I can live in a box, and protect my box, I’ll be fine. Let’s just make the box bigger, stronger, let fewer people in. It is an illusion. We have forgotten that human beings cannot live in a box. We are human, we cannot live outside of communities.

Besides an organizational consultant, I am also a Reiki practitioner and teacher. Reiki is healing energy that fosters balance and relaxation in the body. It helps relieve pain, anxiety, stress, and depression. In the past 14 years as a Reiki practitioner, I have treated people at mental health, recovery, and AIDS clinics, homeless shelters, and privately. I have treated: social workers and managers, homeless and professionals, people with mental health challenges and recovering from addiction, old and young, rich and poor, republicans, democrats, independents, socialists and anarchists, formally educated and not, veterans and pacifists, from the United States and other places in the world. People generally come to me because their body is hurting, and they’ll do anything to try to make it feel better, even if they don’t believe in Reiki. Reiki brings emotional healing and peace too, but most people don’t believe or care about that in the beginning of treatment. They just want their head, knee, back, sciatica pain to go away. Doing Reiki has taught me about the common good.

There is one thing that I know all human beings have in common: a yearning to connect and be seen, appreciated, and loved. When I hold my hands over someone where they feel pain, I sometimes see images, like photographs stored in their body. My hands become the darkroom for these pictures to come to light. More frequently than not, those images are moments of separation or isolation. A man stopped by the police terrified his family would have nothing to eat if they locked him up. A mother and daughter fighting. The shame of abortion, 50 years later. An old friend walks away after a misunderstanding. A lover surprised with someone else. The immigration police knocking on one’s door.

The most frequent image I see is that of rejection. The personal feels excluded, or unloved, because they feel they do not belong they:are schizophrenic or schizoaffective, alcoholic or drug user, homeless or mentally vulnerable, Black or Latino, have four toes or three nipples, are too fat or too skinny.

As a sociologist, it is so blatant to me that the rise in shootings in the USA and the world is connected to this increased sense of exclusion and fear. Durkeim in 1897, called it anomia, a social cause of suicide. Durkheim said that when social norms change too quickly, as they often do in the post-industrial world, some feel a sense of disconnect and alienation from societal norms, they take their lives to react. I believe that currently, the sense of exclusion is so high, for some as individuals, for others as a group, that many are willing to take their own lives and the lives of others to just be able to end the pain that they feel inside. So to me, it is clear that the rising violence originates from the pain of exclusion, whatever the politics. Hurt people hurt people.

It’s so easy to hate this or that politician, take your pick. It’s much harder to love and talk with your neighbor or family member on the other side of any controversial argument and have a conversation and stay open mind and heart. When we shut down we ultimately hurt ourselves, and store the sense of isolation into our bodies as pain. While we struggle to find legal agreements and long-term solutions, let us not forget the greatest antidote to violence is love, connection, and community. Especially when connectedness and openness takes courage. For when we feel loved, embraced, and connected in community, we safeguard it. So what we do for the common good benefits ourselves as individuals, too.

Our weapons are way too advanced for how immature we are at love. We say “I love you,” but can turn it quickly into hate. It’s harder to love when we are scared, stay loving and open when we are angry, when we are terrified. There is no other option for us to survive as a species.

What if each of us today took someone who has outrageous beliefs and accepted or listened to the story that gave life to them? What if we stepped through the illusion of fear focused on our common good? Societies that pay more attention to the common good are a lot less violent than ours. We must begin to value and invest in our common good. Our survival as a country and a species depends on our ability to learn how to do so.

Photo credit: Louis Waweru

ITALIAN VERSION

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Inclusive Conversations, Uncategorized

Do your conversations these days feel like black holes of despair that transform even the sweetest of donuts into booger-tasting jelly beans? If most conversations you have about these crazy primaries end up in fights and go nowhere, tip #4 is for you. Inclusive conversations occur when differences are seen as a resource, not a threat. Previous tips included preparing the conversation, choosing when and where to invest your energy, opening the door to the conversation and making allies. Today’s tip is more about the actual conversation. Tip #4: No matter how insane you think people are to think the way they do, don’t beat them down with what you know, try to pause, and meet them where they are, instead. But before I explain what I mean by: “meet people where they are,” here’s a little story for you.

Sunday dinner, with my family in Italy and we’re discussing child prostitution. I was probably 20 years old. Yes, in my family this is what we talked about over Sunday dinner, along with everything else controversial, like war, politics, and inevitably, the corruption of the Catholic Church. The final cherry on the cake? The ethics and moral stature of our local priest. And this is where I got my Italian equivalent to what in the United States would be “debate team” training.

Here were our rules:

1) To get the stage, you had to yell louder and gesticulate bigger than everyone else.

2) Once you had the stage, you had 5-10 seconds to make your opening statement.

3) If your opening statement was persuasive, you could keep the stage for another minute, but only if you didn’t get distracted by the five people who were revving up their motors to jump in.

4) If your opening statement was weak, you would lose the stage.

5) If you paused, you’d lose the stage.

6) If you stuttered, you’d lose the stage.

7) If you had the stage for a whole minute, or two (which meant you were a pro) you had to have a final punchline to end your point to win.

8) If you lost, someone would interrupt you.

9) If you won, someone would interrupt you.

Brutal rules, I know. It was our bonding time. Bonding through fire. Our Sunday dinners were notorious for being loud. Even with the doors closed, neighbors on the street could hear us arguing. And Grandmom’s (Nonna’s) house is an earthquake-proof cement house in the open country-side and the street was a quarter a mile away. The men joked that they needed a traffic light to get a word in edgewise. We are a determined bunch of folks. We could run you down with words, any day, anytime of the week, just to be right. With this kind of training, I’m sure you’re not surprised that conflict in my family is an everyday affair.

Hot peppers (that my grandmother planted) in front of her house in the countryside. The road borders the property. The houses in the distance are on that road.

But back to the child prostitution dinner. “You have to persecute the men, because the men are the clients, and without them there would be no…” my aunt yells. “Go after the traffickers, you know the mafia is allied with those crappy politicia…” my other aunt interrupts. “It’s all the priest’s fault”, my uncle says, just to instigate the crowd. This is 15 years before the catholic sexual abuse scandals. The men in my family blame priests for everything. It is their weekly excuse for sleeping in on a Sunday morning instead of accompanying their wives to church.

An uncle who has been quiet so far and really hates the exponential volume of these conversations, finally screams: “What the hell do we care? Really? This doesn’t affect us!” Perhaps this was an ill attempt to quiet things down but I was livid.

“It’s that type of not-giving-a-damn-attitude that puts girls at constant risk…” I yelled. I listed every study on violence against women I could think of. I kept the stage for a whole two minutes. My heart was pounding as I was yelling at the top of my lungs. And then my last fatal blow:

“Let’s see if you care if it happens to your own daughter.” He was immediately offended and shut down. He got up and may have gone to the bathroom. Everyone else got up to clear the table. We dispersed. We moved on to talk about the mafia and the politicians’ role in everything that is wrong with our country. I’m thankful for my brother who said to me that day: “You’re right and you make good points, but your tone is so condescending no one will ever listen to you.”

The view of my grandparents’ land and tobacco fields.

A few years later, someone told me something very similar. We were having dinner at my place in Rome, with some of my African friends. We had a fiery conversation about the United States’ international imperialism. A dear friend said to me: “You know more than most people do about this stuff, but the way you talk, you push away people who could be allies, instead of helping them get curious to find out more.” That’s when it finally hit me. No one listens to what we say when how we say it makes them feel inferior.

After six years of college in Italy and six years of grad school in the United States studying the history of racism, discrimination, and exclusion all around the world, I had more material that most to offer a great, easy to win debate. Academia taught me to not win a debate by interrupting, but with logic: name the assumption your opposition is working from, display ample historical evidence that proves those assumptions to be wrong historically, move to how the historical evidence lives on today. Propose a solution. Final punch. It was a different tactic, but it created the same effect. There is a winner and a loser.

We are taught to debate this way in the academic world, it helps us establish credibility, prove we are qualified and gain self-confidence in what we know. But the systematic beating people down with evidence is not effective at helping people see another point of view or at making allies. Both parties in the conversation eventually walk away empty. The “loser” walks away feeling horrible about themselves. They also walk away feeling horrible about the world we live in. This person’s curiosity is not stimulated. The apparent winner may feel an ego boost at first, but eventually feels disconnected and alone, depleted by the conversation too.

Great teachers know that they cannot teach a student unless they know first, what the student already knows. New knowledge depends on pre-existing knowledge. Communication specialists will tell you that that unless you know what your audience cares about, you cannot communicate effectively with them.

So for today’s tip, instead of beating people down with the knowledge you have, try meeting people where they are. This expression is common so here are four ways I’ve learned to do this that I recommend:

- Find out what the person’s current knowledge is on the topic.

- Find out what the person cares about in other aspects of their life.

- Give up any false sense of superiority and talk to them as peers.

- Prioritize the message with very few points and relatable examples.

- Relate your key points to the topics the other person cares about.

- Ask questions, before, during, and after. The conversation is not over once you make your point. There is no touchdown scoreboard.

- No matter how much you think you already know, make sure you learn something from the other person too.

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Racism, Uncategorized

African American people taught me how to live well, at peace, while feeling like a fish out of water. It hurts to watch how many people, and our media, assume that violence is norm in Black culture.

By the standards of most Americans I am an incredibly weird person. I am an Italian American woman who spent seven years studying African American culture in college, first for a Master’s in Sociology, then a PhD in African American studies. I left a life in Rome, Italy, the eternal city, to study in Philadelphia. I wish I could make a collage with the look on people’s faces, of all colors, when I tell them what I just told you.

I studied to end injustice, but I also studied to make peace with my own dual Italian American cultural heritage. I felt at odds in my own skin.

In those seven years, I did a lot more than study. I grew up, too. The journey started at 23. I got my PhD at 30. And in those seven years, I met two women, who led me, taught me, assisted me, held me, and walked with me in the path to becoming a woman. Both of these women are Black. So I joke at times that I’m an Italian American raised by Black women. Without these women, I could not be who I am. They taught me to love myself unconditionally, forgive myself, express myself, express my art, stand and walk in the world, while never fitting in.

It’s been ten years since the PhD and I’ve continued to grow. I’ve continued to listen and learn about Black folks in America. And I feel that I understand now that while my mentors are phenomenal individuals, their lessons were cultural, from a collective experience. They taught me some of what their families had taught them: how to survive in the face of incredible adversity.

I’ve reached the conclusion that Black people are the ethical anchor of our country. Because of ongoing discrimination, in housing, education, voting, employment, health, and the criminal justice system, Black folks have needed to dig deeper into their humanity, their resources, their talents, their networks, than anyone else in order to survive America. Of course, many other people of color have experienced these challenges, too. Over the years, I felt an affinity for African American culture that made me want to know more.

To me, the reason why Black folks dominate the art world is because they’ve needed to use art to express their deepest pain, injustice, and emotions. From old spirituals to blues, Nina Simone to Miles Davis, India Arie to The Roots, art has become a vehicle for humanity, for expressing humanness, aliveness. Playing hearts, souls, and pain through the beat of drums, voices, guitars, trumpets, saxes, and basses.

I’ve traveled the world. Yet in my experiences, Black folk in America, as a people, have deeper compassions, feelings, and forgiveness than any other culture I know. They have been trying to forgive white folk for hundreds of years of injustice. They’ve been nurturing community and organizing peacefully as long as they’ve been on this land.

Dressed in Sunday’s Best

I know most white folks are scared that Black folk will become violent and attempt to turn over the social order and be on top. This has not happened and will not happen because Black folk will not do to whites what we did to them because the majority of Black folk have worked hard and work hard every day to be productive, patient, and loving. To believe that a better world is possible. To not judge the few for the actions of the many.

Spirituality upholds Black folk. The strong connection to each other, to God, to a higher power, to prayer, to whatever you want to call it, that connection has kept Black folk alive and positive for centuries. Have you noticed how in Black neighborhoods there is a church every few feet? Learning to elevate one’s heart, mind, and soul above limiting circumstances. Moving mountains with kindness. Drawing strength, never easily, from the bowels of existence, which in the words of W.E.B. DuBois “dogged strength alone keeps from being torn asunder.”

Most of us white folk are so attached to having things our way that we lack the same capacity to be positive through hardship, love through challenges, patient when times or tough, and to express when we’re in pain. Think how much you would love your neighbor if you knew that their great-grandfather had raped your great-grandmother, during slavery, and that your neighbor’s family has forgotten this, but yours has not.

How much would you love your neighbor if your neighbor’s brother also worked for the police force that killed your dad when you were 5? And your brother when he was 15, and your best friend when he was 20?

Now add on the fact that your neighbor also has better access to better healthcare, education, employment, housing, legal and political representation than you. Would you even try to love your neighbor? Would your protests against inferior access to healthcare, education, employment, and legal representation be peaceful?

It is this ability to connect with humanity, with humanness that causes white folks to be so enamored with Black music, culture, food, fashion. We white folks reach out to Blackness to connect with our own humanity.

A rally attendee on a scooter holds a sign reading Black Lives Matter at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco.

This is also why I believe when we white folk say something we know is questionable in a group conversation, we look at Black folk for a reaction. Deep down, we know Black folk are the measure of our humanity. We know they are the measure of whether what we said was fucked up.

Most Black folks are already modeling humanness with incredible compassion and grace. But we cannot demand they do what we as a country, don’t do.

Our country is a ship in the waters of ethical confusion. Black folk are the anchor. They anchor us with the deepest and most profound parts of our country’s humanity: our ability to love, to create, to forgive, to connect, to organize for justice.

The waters are getting choppy. And the captain–society, the government, white folks, our institutions–is revving the motor. How can we expect the anchor to keep the ship grounded?

Every murder is an acceleration. Every child charged as an adult is an acceleration. Every bargain deal accepted by an innocent man is an acceleration. Every person in prison because they cannot pay a fine is an acceleration. The ship cannot stay still if the acceleration continues.

It is unjust to expect Black folk to anchor our collective ship.

The chain linking the anchor to the ship is breaking.

So whomever you are, wake up. Find your humanity. Choose whether you want to keep revving the motor on our ship or demand it stop. Get involved to change the conditions that are generating this insane acceleration. Join an organization, that suits you, that is working to slow it down. There are many.

Langston Hughes described it well when he wrote:

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?…

Or does it Explode?”

Langston Hughes

***

I wrote this in response to the killings of Philando Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling by the hands of police officers. May your souls rest in peace. May your lives not be ended in vain.

Five hours after I wrote this, Micah Xavier Johnson, a Black man who had served in the United States Army in Afghanistan, earning several medals, shot 11 white police officers, killing five, in Dallas, TX.

Images:

Dressed in Sunday’s Best by Su-Chan

https://www.flickr.com/photos/su-chan/

A rally attendee on a scooter holds a sign reading Black Lives Matter at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco.

By Pax Ahimsa Gethen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50063410

by Rita Fierro | Oct 18, 2019 | Antiracism, Racism, Trauma Transformation, Uncategorized

We have work to do. The election of Trump has ripped the bandaid off our modern myths of justice, revealing the collective wounds we swept there after the Civil Rights Movement. While our society shifted to a more inclusive society in the 1960s, fifty years of good intentions does not erase 350 years of horrific deeds.

Our wounds have been festering for centuries, cyclically reopened by violence. We are now being called to face our demons and to heal more fully, together.

Persecuted white Europeans migrated here only to enslave others and transfer their victimhoods onto indigenous peoples and Black people. As Black people have rebelled at injustice, at each advancement white people have been reminded of their own ancestral wounds the pain of which increases with privilege lost. Every person and every culture can transform this pain, can create a new pattern, but we haven’t yet.

In the Civil Rights Movement, we tried to create new patterns using nonviolent tactics aimed to replace fear with love. Northern white liberals used these methods only to transform the hateful hearts of Southern racists without redirecting our energies back onto ourselves, our communities, and local economies.

In the north, we barred Blacks from unions, allowed housing segregation and job discrimination to continue, and decided having Black people sit at lunch counters was change enough, turning a blind eye to the truth that many didn’t have money to enter the restaurant at all. We betrayed justice and fed ourselves tales of victory, focusing on the new handful of Black faces populating our neighborhoods, restaurants, and workplaces. We did nothing to support the majority of Black folks whose poverty, injustice, and incarceration rates were rising. The non-violent movement in the south became the violent rioting movements of the north because when racial justice was needed economically, whites chose to turn back to our privilege and live complacently.

As whites, we must feel our wounds again now. We must look into the mirror. White folk of all shades, now is our opportunity to atone, heal ourselves and our ancestral pain.

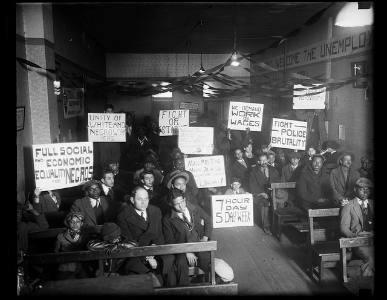

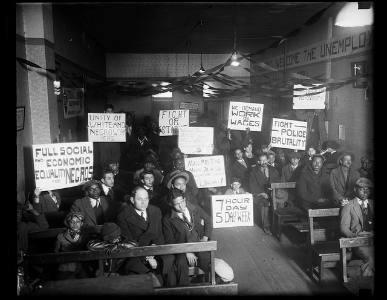

Civil Rights Protest, 1965

For us people of color, the original wound stems from slavery. The original wound was a loss of self, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. An overlooked piece of our journey to freedom is that slavery was only 1/3 physical. Most of us have not made it to freedom. Our bodies may have made it to the north, but our minds and spirits have yet to reach their destination.

The trauma of slavery has affected our ability to respond. We often take the blame for things that aren’t ours and blame others for things that aren’t theirs. Taking responsibility means, quite literally, the ability to respond. We need to intentionally remember: our history, our strength, our journey, ourselves and our spirit because there has been an intentional dismemberment of those things in our communities. The plan was to keep the body strong and the mind and spirit weak.

The Civil Rights Movement brought lots of gifts including a wound of unkept promises. As African Americans in this country we don’t get to live our lives as individuals. We are seen as the collective “we” everywhere we go. This “we” is simultaneously bonding and supportive and binding and restraining. The illusion of the Civil Rights Movement was that we would finally live as individuals.

When Martin Luther King died, many of us abandoned love, choosing fear and anger instead. The pain of losing Martin was too much for us to bear. When they killed him, some of us started to believe that love didn’t always win and we wanted to win. So we put back on the cloak of fear and anger and started to fight again.

Each side has its share of the collective wound, two sides of the same coin. But now, as a nation, we face a choice.

Black Lives Matter protest, San Francisco

If we repeat the cycle of violence, our weapons are stronger than they were 60 years ago. It’d be easy to self-destruct this time. If we choose to heal, we can become united like never before. Here are the ways we can heal, build a foundation for a new movement, and reach unity:

(1) Clean the Wound, Face the Truth

Let us remove the niceties, the fake stories of glory, the arrogance of superiority. Let us face the truth of our country’s history: We are not an exemplary democracy. We have nothing to preach about. We are hurting and we are still trying to understand how to create justice. It is time to feel the rage and anger that is trapped inside.

(2) Disinfect the Wound, Mourn

We need to grieve together. Grieve with people you trust so we can let go of the past and create room for a new future. Our new movement begins with the courage to mourn communally.

(3) Suture the Wound, Drop the Fear and Reach for Deeper Healing

We must move away from reacting. Step into responsibility instead of reaction, choose purposeful action and if we don’t know that is yet, wait until we do. In giving up fear, we can deepen our understandings and make choices from a place of truth, inspiration, and love. We must give up rushing to action for action’s sake. Go inward first. Healing at the individual level is needed to heal at the system level. Let us aim for deeper healing.

(4) Tend to the Scar, Don’t forget, Instead Act from Deeper Wisdom

We must learn and remember our history. Every right earned had a backlash: slave-breeding followed the end of the slave trade, the Dred Scott case followed the underground railroad, lynching followed Black economic advancement, the assassination of leaders followed the Civil Right’s movement. This is the beginning of the backlash of Obama’s election. We too must do what generations preceding ours have done. We must organize, push, hold accountable, and stay united in the face of fear and national terrorism.

(5) After the Healing of Individual Wounds, Tend to Collective Scars

After bringing our attentions to our own wounds, we can tend to the scars of how we have related to each other. Let’s leave Facebook activism and choose diverse groups of people we can unite with face to face. Build your skills and engage in hard conversations. Learn to lean on other brothers and sisters.

(6) When All Scars are Healed, Build a New Movement

Once the wounds are healed we can build true unity. We may still hurt each other from time to time, but we will know how to transform this pain instead of transferring it. We will be stronger than ever, and we will put together the lessons of the past to build a new movement.

The dialogue of our election campaign revealed an adolescent nation at best. We are being asked to grow up. It’s a moment of initiation. And as is true with most initiations, there is a real chance we won’t make it. Complacency could cost us 150 years of social progress. However, with a foundation of healed wounds, we can respond instead of reacting. Once we can do that, we will be undefeatable. There is a path forward. Blessings to us all on this journey.

Recent Comments