I’ve been integrating Participatory Leadership practices with Evaluation for years now. It started simply as a way to bring two passions together. After systematic reflection, blogging, proposal writing, co-editing a journal issue (New Directions in Evaluation, Spring 2016), and teaching trainings on building the bridge between evaluation and facilitation, I have become a lot more aware of the critical importance of this bridge for evaluation practice in service to our changing world.

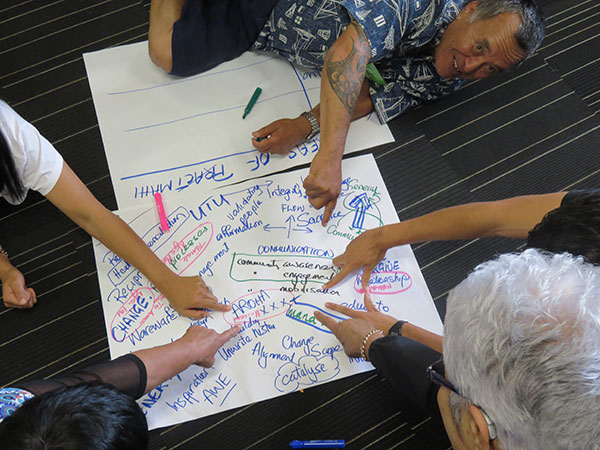

A drug and alcohol prevention network uses participatory leadership to help identify priority work areas in Auckland, NZ.

- Creating a Positive and Future Forming Reality. Participatory Leadership practices help shape the future in terms of possibilities and opportunities. As Gergen (2014) points out, if research does not take an active role in helping participants envision new, innovative, and positive collective realities, then our research methods only mirror back a negative view of current reality, de facto supporting the status quo. With its focus on collective intelligence, participatory innovation, emergence, shared decisions, and shared ownership, Participatory Leadership practices are future forming. They help groups identify powerful questions to inspire, move forward, and overcome challenges. I use evaluative tools to document that movement forward. I also use facilitation tools that in the Art of Hosting community are called harvesting tools (graphic recording, video recording, mind mapping, notes of conversations, doodles, post-its, etc.) to show what took place and what decisions were made.

- Local People (Stakeholders) Drive the Agenda. In most evaluations, even participatory evaluations, evaluation capacity building, and democratic evaluations, the evaluator generally decides in which phases of the evaluation process stakeholders will participate: evaluation questions, design, purpose, methodology, methods, or reporting. Participatory Leadership practices can be used to allocate more space for the needs of local people to drive the agenda of conversations that precede planning by answering the following questions: 1) What conversation does the group need to have to be strengthened in their purpose, collective work, and effectiveness? 2) How can we use the evaluation to hold the space for these inspiring conversations? 3) What evaluation and harvesting practices can we use to document these conversations?

- Building Dialogic Capacity. Participatory Leadership practices and theories help us reflect on the pitfalls of oppositional talking, or debating, and the creative power of true dialogue. We challenge participants to move beyond oppositional dialogue into deeper listening and creative conversations. In doing so, the group’s builds its capacity to engage in genuine, creative, and generative dialogue.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage in storytelling in Christ Church, NZ.

- Culturally Affirming. While there are evaluators who work all around the world in a variety of cultural contexts, the theory and practice of evaluation are still dominated by Western worldviews. For the non-believer, the evaluation language can often come across as linear, cold, distant, emotionless, complicated, rigid, and somewhat out of reach. While participatory evaluation and capacity building evaluation use activities to make evaluation more approachable, Participatory Leadership practices focus on the atmosphere we create in our meetings: a welcoming, more heartfelt environment where different cultures are welcomed and have more freedom to be who they are. I wouldn’t say that Participatory Leadership is culture-free, yet it isn’t as tightly constrained and culturally prescriptive as other approaches (timeframes are flexible, agendas shift depend on participants’ reactions, participants have space to raise their own issues or start their own conversations). There is more space for counternarratives to be told (more detail on this to follow in another blog).

- Advocate Inclusion and Involve Large Groups in the Design. Participatory evaluations typically involve small groups because many believe that the more people involved, the harder it is to reach decisions. Participatory Leadership practices enable us to work with large groups using relatively minimal resources and generate meaningful information to inform evaluation design and practice. For instance, a skilled group of facilitators can conduct a World Café or Open Space with 150 people in 2-3 hours to inform the Evaluation design. Some Democratic Evaluations also involve larger groups, because the evaluators are trained in dialogue and deliberation.

- Hosting Polarities and Power differences. In my experience, management can gatekeep and ostracize participation in decision-making more because they lack the skillset to handle opposite opinions productively than for ill intent. Participatory Leadership practices help the evaluator prepare for, plan for, and host dynamic tensions and power differences in a way that is both respectful of all individual parties and productive to the group.

Participatory Leadership and Evaluation training participants engage at the AEA conference in Denver, CO .

- Holding Space for Complexity. Using the Cynefin Framework as a point of reference, the comfort zone of an evaluator, generically speaking, is most likely to be the realm of the complicated. Our logic models are generally created, tested, and validated with complicated frameworks in mind: several causes generate several effects, in a mixture of linear and non-linear ways. However, the contextual factors and external factors in our logic model designs are areas of complexity that are often listed, but not deeply investigated. Participatory Leadership practices allow space for the investigation of the complex within our evaluation designs in a way that is meaningful and productive to other aspects of our work.

Our world is changing rapidly. If it is true that there is an unsustainable, self-destructive trend in our world, it is also true that there is another one: innovation, cooperation, and community-building. Participatory Leadership can bring tremendous strengths to our evaluation practices as it incorporates skills to engage groups and communities in an inspiring way around what to do with the current struggles of our world. In doing so, Participatory Leadership trains us to see the potential in the unknown, the emergent, the unclear, the out-of-control. And as long as we are dealing with human beings, the unknown, the unclear, and the unpredictable is always near. We can try to control it, just to satisfy our own compulsion and need for a security blanket. Or, we can immerse ourselves in the transformation and put our evaluation skillsets at the service of conversations that people need to have in a changing world.