Just before this groundbreaking week, I attended a four-day Theatre of the Oppressed training for facilitators. This was my unintentional preparation for a week in which the South Carolina shooting and less-heard burning of Black churches, the Supreme court upholding of the Affordable Care Act and Gay Marriage. Whatever side you are on, the mix of these events are making our opinions about difference in America slap us in the face.

Photo by em_diesus

We can choose to do the deep work that allyship, forgiveness, and restorative justiceentail. This work is never comfortable. When we face the beast, we often want to run away. Most often this is because we discover that beast who we hate outside of us, is also within us, we have internalized it. We are not immune of the context we grew up in. I’ve learned that I no longer do this work to help others. I do it to embrace my own humanity in how I show up for others, but also how I show up for myself.

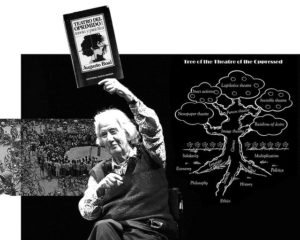

There are many different approaches to doing this “work.” One is the Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a groundbreaking way of using theatre and improvisation in groups to help people engage individually and collectively with how they have been affected by power structures and beliefs. Created by Augusto Boal, it is grounded in Paul Friere’s powerful Pedagogy of the Oppressed. By being spect-actors, simultaneously spectators and actors, participants have a chance to both reflect on a situation and offer strategies to overcome the challenges each solution presents.

I tend to take on a role in groups, one in which I challenge the group to go deeper. At times I’ve been painfully scapegoated for it. But the group in my Theatre of the Oppressed training was a singular group of people who are brave themselves and who are as passionate about facilitating conversations about power, inequity, and justice, as I am. So they welcomed my challenge and bid me higher, pushing me way out of my comfort zone.

In some small-group work, we set up a skit of a summer backyard party in which the owner, a white woman, Sally, who recently moved into the imaginary neighborhood, tells off the Black guy, Jamal, who’s lived in the neighborhood for generations, because he plays loud rap music from his car in front of her house. A friend and ally, Kate, steps in to support the Black guy and calm Sally down, but Sally is drinking. She gets louder and louder, nastier and nastier. As her sense of entitlement grows, so does her escalating rage. Here are some things she says:

“Not in my neighborhood.”

“I didn’t spend all this money to live in this neighborhood to hear that music.”

“This is why we don’t like people like you moving in.”

“What’s wrong with you people?”

“Shut that music in front of my house. This is my property.”

When Kate steps in to ask Sally to not treat her friend Jamal this way, Sally hesitates for a second, but then keeps going, even louder.

“Stop talking to me, I want the music off, NOW.”

Augusto Boal photo by LCR SAP

Kate is turned-off by the ineffectiveness of her attempt to support Jamal, she physically takes two steps back, even if she still wants to help. She doesn’t know how, the violence puts her off. Jamal is left to confront Sally. He is peaceful and brave. He offers a handshake: “I’m a neighbor, nice to meet you, can we talk about this?”

Sally barely concedes her fingertips, showing her disgust for touching him.

This was a theatre moment. But it truthfully depicts how quickly things can precipitate in our own U.S.A.

I was the one who played Sally’s role.

The instructor suggested: “Boal says there is a bit of the oppressor in all of us. I challenge you to discover what playing the oppressor will teach you.”

It has taken me two weeks to write about this powerful experience that Boal would call “the oppressor within.” The experience was as enlightening as it was horrifying. Here’s why.

- It wasn’t hard. I wanted to think of myself as such a “good person” that it would be awfully hard for me to stay in character. It wasn’t. I had a repertoire of experiences to play the role: a combination of conversations had, listened to, ways I’ve been treated, and emotional truth.

- Dismissing human beings. In Sally’s role, it wasn’t hard for me to dismiss these two human beings and anything they said to get what I wanted. What I wanted in that moment was more important than anything else. As if Jamal wasn’t a human being, he was just an obstacle to be removed.

- The ball of anger. Yelling at Jamal was like taking everything that had ever hurt me, from being made fun of in nursery school to being fired on the job, any resentment for anything I believed should not have happened to me, and channeling through, no against him. This was a spiral. Once it started, it was addictive. It was easier than I thought to let it escalate.

- The shame. After I stepped out of role, I had a deep sense of shame. I felt others more distant. Were others judging me for playing the role like I had? Were they asking themselves if this is really who I am? Is it?

- The isolation. Also after I stepped out of role, I felt so isolated, that I was questioning the foundation of my own humanity. I felt alone in the world, disconnected. I felt a sense of despair that only human contact could nurture away. John A Powell in a recent interview said “The issue of race is an issue of belonging.” In that isolation, I was terrified of not belonging anywhere. Thankfully, I know how to reach out for connection. I’ve learned to ask for help. How do the people who embody this harsh role to an extreme feel on a day-to-day basis? It brought to a tremendous sense of pity.

The oppressor in me is completely disconnected from others and my true self. The oppressor in me is judgmental, harsh, ruthless, entitled, but also isolated and terrified. The oppressor in me is my inner critic. Confronting the oppressor outside means also confronting the one within. The scope of this work is not navel-gazing, guilt, or a shallow helping others. It is: to “initiate a healing process toward freedom and justice.”

The goal of theatre of the oppressed though, is to offer strategies, not solutions. So what makes this role true for me? What part of our oppressive society have I taken in and do I play against myself and others? How do I overcome those roles?

The more I work on my within, the more I walk and work more boldy in the world.

Photo by em_diesus